Pete Collard, curator of the Home Ground exhibition, lifts the lid on stadium architecture

Skip-found plans for Anfield’s early design, tea-stained blueprints, award-winning photography and rare scale models, all tell the story of how football stadiums developed at an engaging exhibition at RIBA North + Tate Liverpool.

Home ground: the architecture of football has been put together by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and is free to see. It runs until January 25.

“Putting this on in a gallery environment really elevates the idea of stadium architecture,” says RIBA exhibition curator Pete Collard. “It is almost like an art form in some cases. The aesthetic of football stadiums has evolved so much. Early grounds were revered but they were quite basic, really.”

“They were built pragmatically, often with low budgets. Football clubs in the early 1900s, even though the game was growing in popularity, didn’t want to invest a huge amount in their stadiums, and just provided fans with a terrace and one grandstand.”

“But then there’s something very beautiful about these early drawings of which we have some lovely examples. You can actually see tea stains where somebody has taken the plans on-site, they’re a bit worn and dog-eared.”

“There’s one drawing we have, very kindly lent to us by Liverpool FC, which is a very early plan of Anfield, the Kop as it was first built, which is almost like the Holy Grail of stadium architecture – it’s lovely to put this in a museum environment for visitors to study, admire and engage with.”

“The new Everton stadium was the catalyst. This is the biggest and, one half of the city would say, most important, new building to be built here this year, next year, probably for the next five years. It’s a half-a-billion-pound investment and a wonderful new landmark for the city. That was the rationale, that we could use the new stadium as a starting point for a conversation about the history of these buildings.”

Overlooking the Mersey from its dramatic vantage point of Mann Island, RIBA North + Tate Liverpool is the ideal museum-grade gallery space to host a show inspired by the gleaming new landmark just along the waterfront. The recent opening of Everton’s strikingly contemporary dockside arena, the Hill Dickinson Stadium, has given Tate housemates RIBA the perfect platform for this architectural journey.

“Everton’s new stadium has provided us with a wonderful opportunity to celebrate what are some of the most important buildings in the world,” says Collard. Beyond Bauhaus, problematic urban spaces and sustainability though retrofitting – these are some of the themes covered at RIBA’s recent exhibitions.

“We were keen to create something that was a bit more accessible in terms of what architecture is, a little bit more informal than the exhibitions we would usually do in London.”

RIBA has duly turned its focus to a subject close to Collard’s heart: “Every city, every town has a football stadium, it’s an iconic, important part of local culture, it’s a place we go every Saturday, every Wednesday, come rain or shine, hoping for a win”. Collard should know – he’s been following his local team wherever he lives. But he’s also an expert in his chosen field of architectural design.

“The history of football stadiums is fascinating, because it allows you to show how the game has grown over the years. It recognises these historic buildings as key parts of Britain, Europe and around the world.”

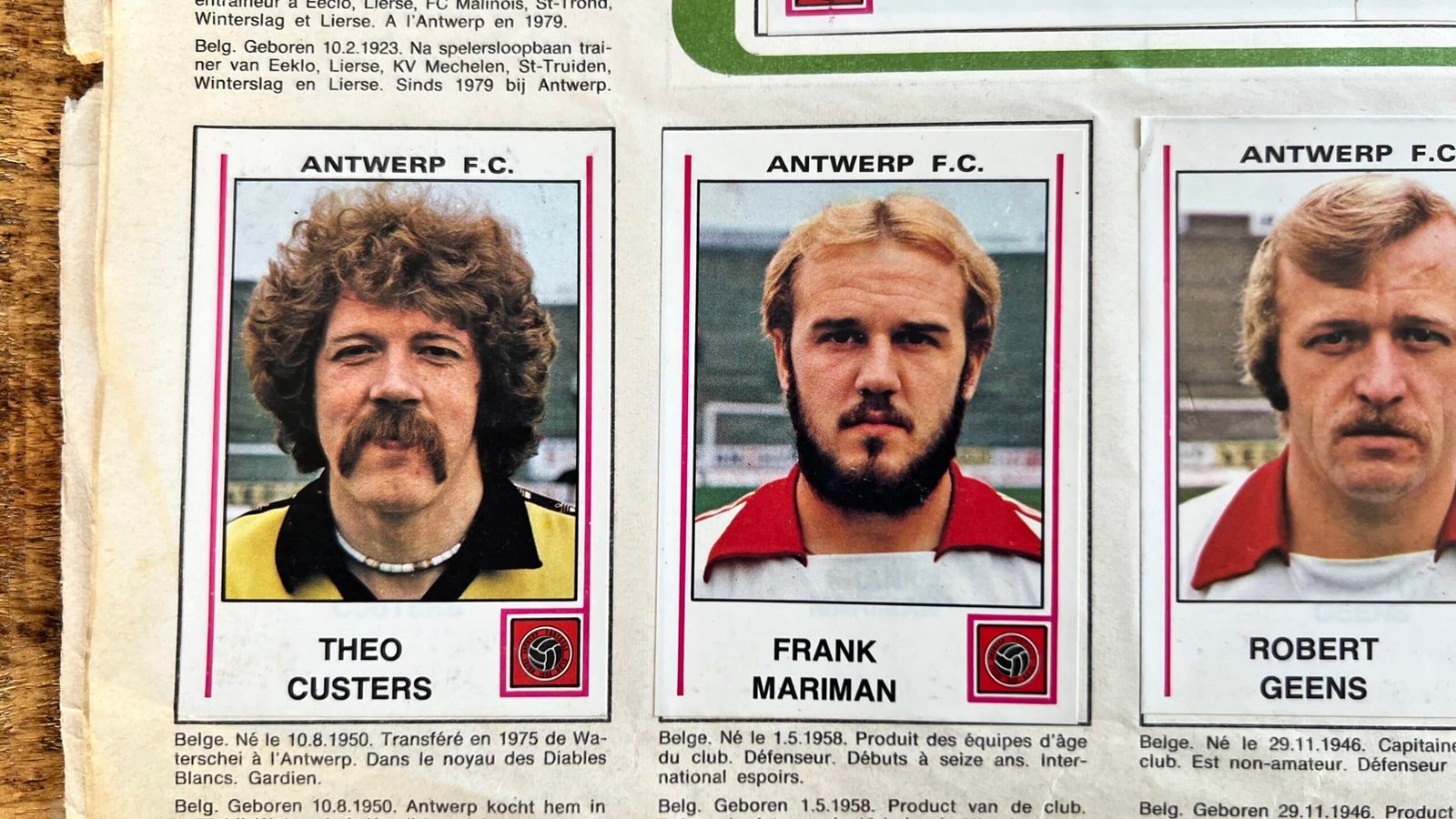

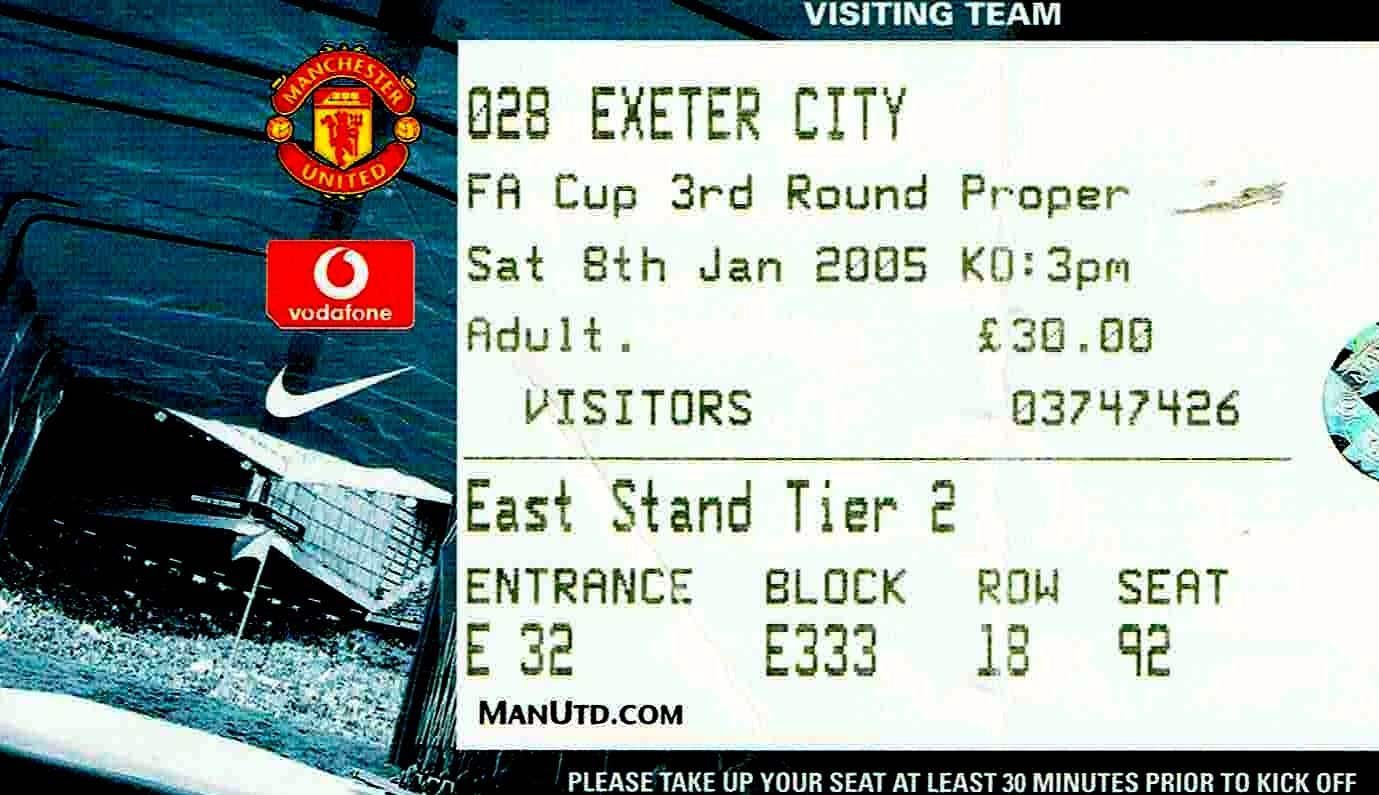

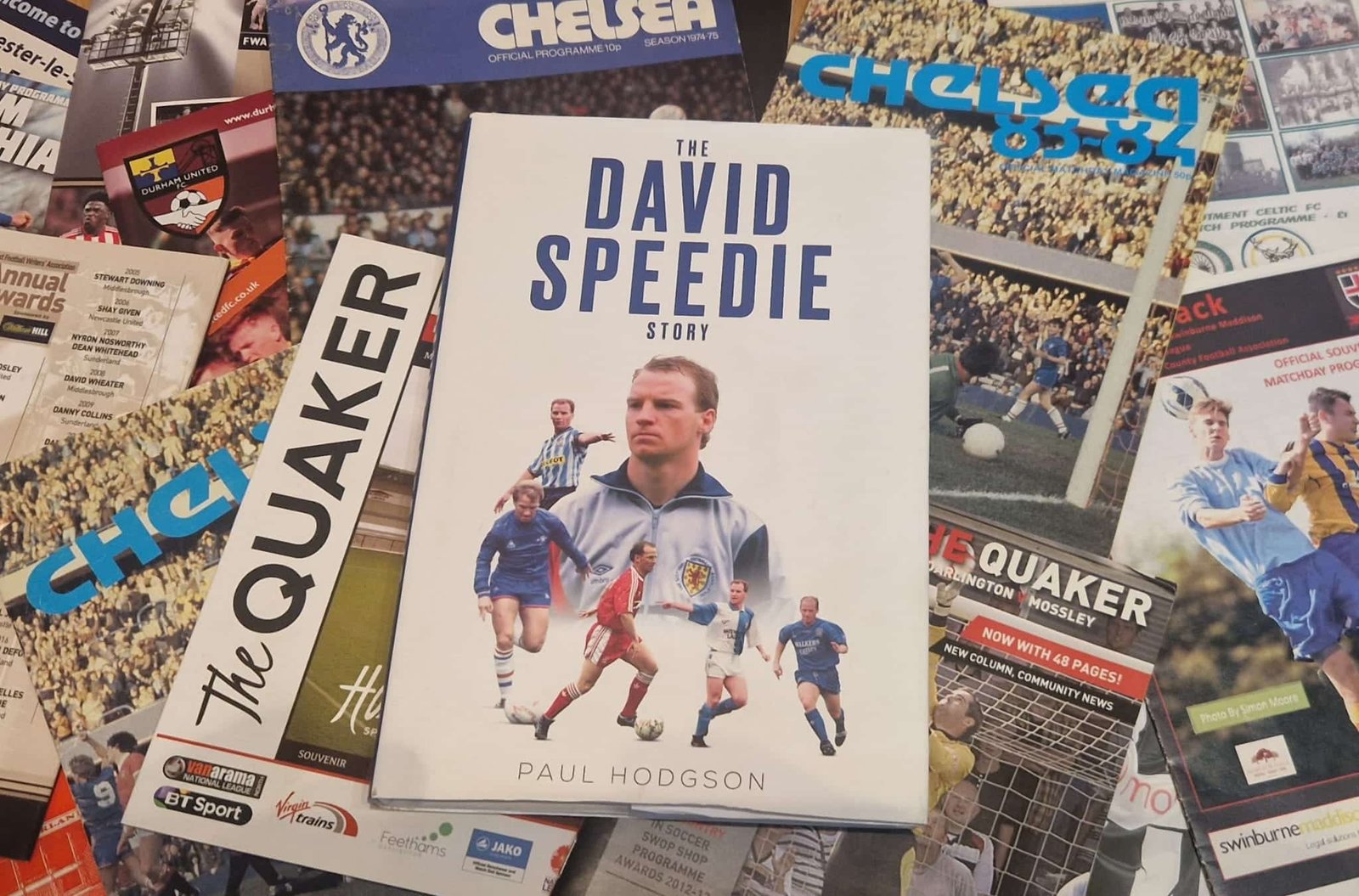

“As a fan myself, this was a real thrill to have been able to put on a show like this, because ten-year-old me was remembering all of his stats – as a kid, when you grow up interested in football, a lot of it is about the detail, where the grounds are, their names and so on. That makes it fun to celebrate the history of the game through the stadium.”

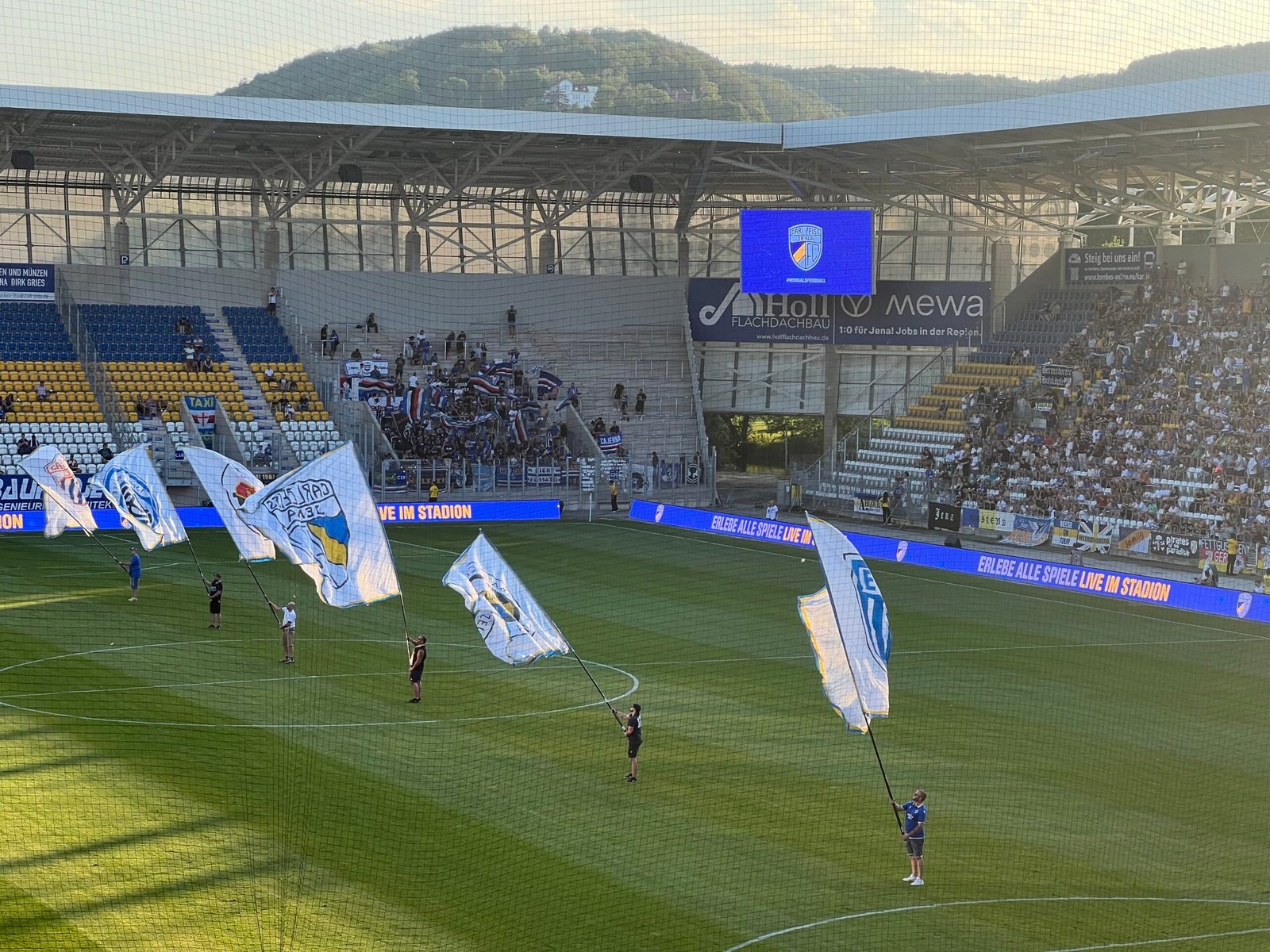

“So for me, it was a chance to revisit a lot of the places I’ve gone to as a football fan, I’ve travelled a lot and also got to feature some grounds that I’d like to go to, the ones I think are important. It’s primarily British architecture but we’re also looking to Europe, South America South Africa, to talk about this from a global perspective.

‘The hardest thing was what to leave out. People ask, ‘Why didn’t you include this place or that?’ Borussia Dortmund, for example, isn’t featured, there are some real iconic places that are not in there. Space was the key factor, but also the materials available, because we wanted to show the architecture of the stadiums.:

“To do that we either needed models, drawings and plans which would be able to tell the story of the stadium and its architecture, while being an interesting and engaging exhibit on their own. I was trying to source early drawings of the Bernabéu in Madrid – sometimes it just doesn’t work out.”

Other times it does. Those intricate hand-drawn plans of Anfield dating to 1906, showing where the Kop was to be built, were rescued from a skip outside the city council surveyor’s office.

“It’s been a bit of detective work trying to put together a show like this. We’ve got photographs from an archive in Uruguay, models from Portugal and Italy… And then we had to fit it all together into something that works in a gallery environment like Tate Liverpool.”

“Then it was a question of how to group the material into sections. We have one on Archibald Leitch because we cannot not feature him, he’s the godfather of stadium design in Britain – including, of course, Anfield and Goodison Park, so there’s a very strong Liverpool connection.”

Some 40 pre-war grounds began life on the Scots architect’s drawing board – plans of the kind chucked into that Liverpool skip decades later. “We show the early relationship between football clubs and the cities they represented. The idea was the stadium was put up on a piece of land that was perhaps quite cheap, often surrounded by housing. Goodison Park and Anfield still are great examples of this.”

“The stadium is a massive structure but set within the heart of the local community and among the fans who go there every Saturday. It is about football, it is about architecture, but it’s more than that – it shows the connection between sport and people, and how leisure-time pursuits have grown.”

“We thought that a timeline would be the best and easiest way to illustrate this. The first exhibits are black-and-white footage that we’ve very kindly been able to use from the British Film Institute, short clips from the early days of cinema. They show Anfield in 1901 and Turf Moor in Burnley in 1903. Those are some of the earliest items, going right through to the modern era, into tomorrow.”

“We’ve got Forest Green Rovers and the new Kop at Wrexham, which hasn’t even been built yet, as we wanted to look forward as well as looking back. We look at the World Cup, which has been a big catalyst for some of the major stadiums around the world. We have a focus on Italia 90 which, from an architectural point of view, was a key World Cup in terms of investment, and what a stadium could or could not be.”

“We feature the Feyenoord ground in Rotterdam, which was a wonderful Modernist construction, built in the 1930s, so an important architectural story, but it’s also where Everton won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1985. Aside from the architecture, there’s often a particular match people might recognise or remember. There are all kinds of ways you can look at it.”

“We look at early European stadiums from the 1930s, discussing how in Europe, stadiums evolved in a slightly different process. Often the city would build a stadium for clubs to play in, particularly in Italy, which is something of an issue for Serie A clubs who don’t own their own grounds.”

Other long-term topics are also addressed; “Often clubs need a bigger ground because they need bigger revenue, which can then be re-invested in the team. The bigger the ground you’ve got, generally the better you’re going to do. So, do you stay in your historic site within your community and main fanbase, or do you move to the edge of town? And that’s a question that will be ongoing for many years to come”.

Recent aspects of stadium development may not have been foreseen when the game in England was transformed by the change to all-seater stadiums 30 years ago. “The history of football stadiums is also the history of Britain and of British culture. Look at the crowds on those early black-and-white films on display, they’re predominantly male, working-class spectators who would go – this was a working-class pastime at a time when wages were increasing, and people could have leisure pursuits.”

“These days, I take my daughter along to see Dulwich Hamlet Women play and she really enjoys it. The exhibition not only talks about the growing popularity of the women’s game – obviously helped by the success of the national team – but also how stadiums were consistently designed by men for men – and stadiums for women’s teams do need to be different.”

“You think about the physicality of sightlines, you’ve been designing for one audience, but actually for the women’s game, you need something very different. That’s something we discuss and encourage.”

“We feature Kansas City Current, whose stadium is the first ever built for a professional women’s team. In the UK, Brighton & Hove Albion are currently in the planning stage of doing something similar. They would be the first club in the UK to do so. It’s a brilliant development, and something we would like to see a lot more of.”

“We also hope younger fans can see how the modern game is so different to what it was at the beginning – today it’s so embedded in society as one of the most popular forms of entertainment. It’s a huge global industry, much of it consumed through TV.”

Aiming to broaden the show’s appeal, RIBA North recently staged a family-friendly day of workshops and creative activities, building a stadium from recycled materials and producing a comic book of match-day memories.

After closing here on January 25, there is the possibility of the show continuing: “We’d love to put it on elsewhere,” concludes Collard. “If anyone’s reading this, we’d love to hear from them. The mission certainly is that it might travel. With its strong European content, it could go overseas. We’ve been speaking with other museums.”

“Obviously, there’s a lot of Liverpool and Everton content at the moment. What is interesting about such a universal subject is that you can add new material and focus more on the city you’re in.”

Home ground: the architecture of football, Tate Liverpool & RIBA North, Mann Island, Liverpool L3 1BP. Daily until January 25, 10am-5.50pm. Admission free.