Budapest provides the shortest groundhop in football, a divide of only ten paces

Dundee? Don’t be daft. Nottingham? Nope. Budapest provides football’s shortest groundhop, but here the divide is much wider than the narrow gap between each ground.

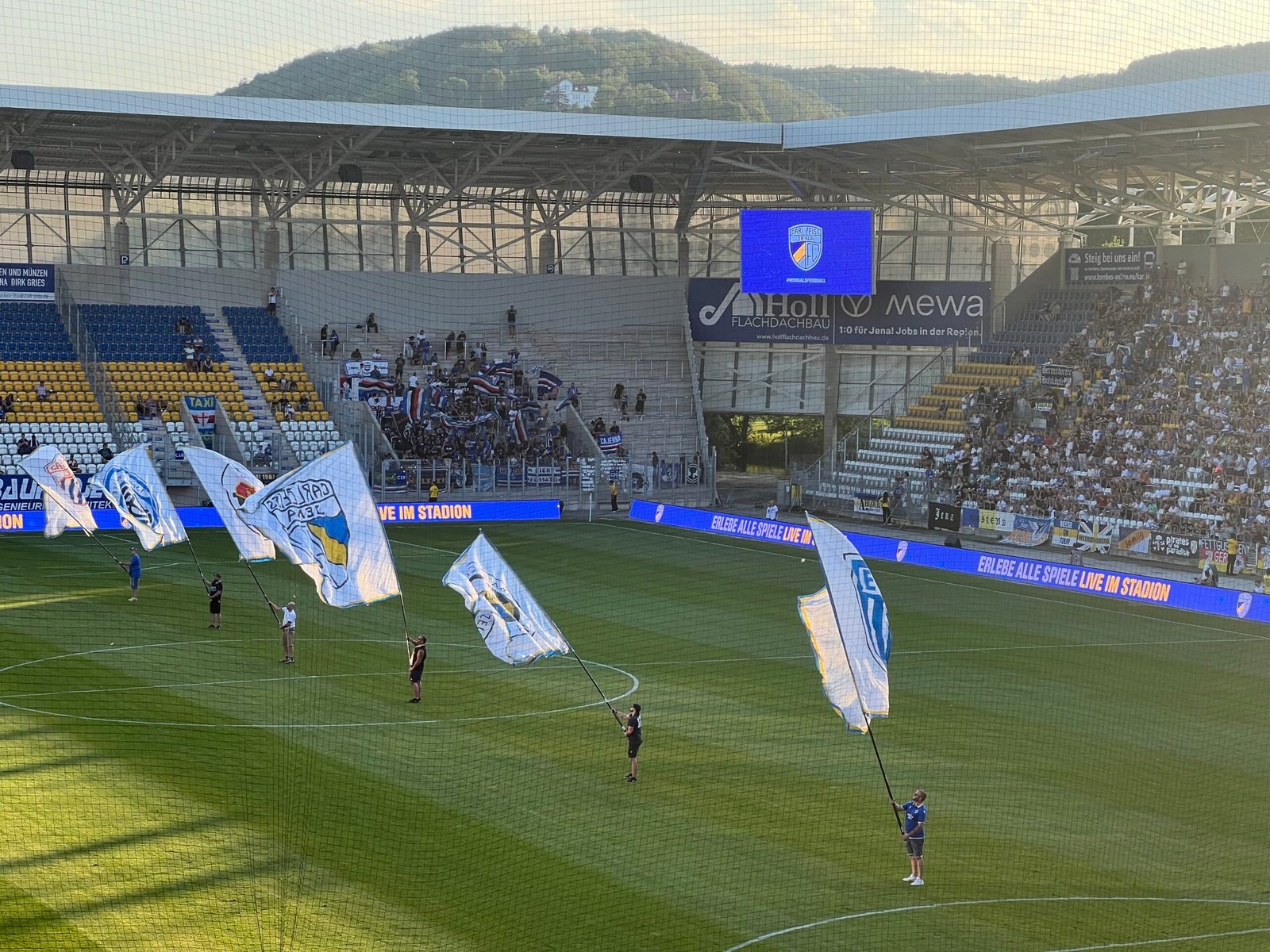

Ten paces, the length of a referee’s march from ball to defensive wall, separate MTK from BKV Előre in Budapest. Ten paces, one division and 81 years, in fact, for MTK’s was opened in 2016 and BKV’s owes its authentically retro look to a 1935 rebuild.

The contemporary venue is much maligned, more resembling a five-a-side pitch at a suburban sports centre, despite the 7.26 billion Hungarian forints or $26 million lavished on it. By immediate contrast, its shabbier neighbour is revered, the outsized main stand just begging to be filled by chain-smoking menfolk in trilbies, filmed by a camera crew from Pathé news.

MTK’s Hidegkuti Nándor Stadion is named after the club’s legendary forward who scored a hat-trick in Hungary’s 6-3 win over England in 1953, football’s celebrated Match of the Century. BKV’s Sport utcai stadion is so called because of the drab street alongside, Sport utca, that delineates that ten-pace gap between the two grounds.

The narrow tram tracks lining it lead to a depot at the far end and link to BKV’s identity as the team that has represented Budapest’s transport company since 1912. Előre is Hungarian for ‘forward’, as in avanti, as opposed to the Hidegkuti variety.

A recommended visit to the gorgeous club bar will reveal pennants from long-lost counterpart clubs across the Eastern bloc, from the days when the European Railways Cup was a going concern and regular finalists like Lokomotíva Košice weren’t the fifth-tier non-entities they are now. This isn’t travelling back in time, this is riding through it in a train carriage while a pocket transistor radio plays pre-match marching tunes.

Formed in 1888, the Magyar Testgyakorlók Köre, or MTK, have 23 league titles to their lengthy name and, more recently, have clocked up four relegations from the top-flight NBI. MTK start their spring campaign in Hungary’s second-tier NBII on Sunday, January 29, against Szentlőrinc SE. One long rung down the league ladder, BKV and their pleasingly numerous cultish groundhopper following must wait until February 19 and the visit of Sényő-Carnifex FC in the third-division NBIII, Eastern section.

In both cases, it’s pretty hard to big up the opposition. Sényő-Carnifex probably won’t be selling out their allocation at one side of BKV’s main stand unless the club’s sponsors, manufacturers of kebab meat, dish out free samples.

The stadium is why groundhoppers beat a path to Sport utca, ‘incomparably beautiful’ according to the BKV website, and modelled on that of Ferencváros three tram stops away. This was 1935, a golden age for Hungarian football, with grounds full across Budapest and a World Cup close to being won three years hence.

After the war, the ground reached its peak of 20,000 capacity, the nine rows of terraces extended to 32 in the main stand, said to have the loudest crowd echo in the land. BKV, then called Budapest Előre, reached the top flight in 1949-50. That season, top scorer Ferenc Puskás played every game for champions Honvéd, Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor starred for runners-up ÉDOSZ (aka Ferencváros) and Nándor Hidegkuti appeared in every match for Budapest Textiles, aka MTK, who had just returned to their newly repaired ground opposite.

Four years later, all would gain global fame after the Match of the Century. Within the same decade, three of them would earn riches and win trophies in Franco’s Spain, while Hidegkuti stayed at home, later opening the 6:3 bar in Budapest.

Back then, his home ground of MTK was much different to the much-mocked new one built on the same site in 2015-16. Comprising a vertiginously steep main stand and open terracing, this proved the perfect double for the Colombes in Paris – where Hungary lost that 1938 World Cup Final – when famed director John Huston made cult war film Escape to Victory in 1981.

Here, Sylvester Stallone pranced around the Allied goal and Pelé hit the perfect overhead kick into the German net. Watch closely, and to one side you can see the back of BKV’s stadium, just across Sport utca.

There was an extra Magyar angle, too, as the plot was partly based on Két félidő a pokolban (‘Two Halves in Hell’), directed by another cinematic great, Zoltán Fabri, 20 years before Huston. Both films lean heavily on the legend of the 1942 Death Match between a Ukrainian team and an occupying German XI in Kyiv, an event whose veracity has been questioned.

By the 1990s, there was no doubt that MTK’s ground was a crumbling ruin. Hungarian football emerged from the post-1989 political changes in poor shape. It would be 20 years before most major grounds, and several minor ones, would begin to be rebuilt by the ruling Fidesz Party.

Chairman of MTK from 2010, Fidesz bigwig Tamás Deutsch oversaw the convoluted reconstruction of the Hidegkuti Nándor Stadion, which required a 90-degree rotation of the pitch and a disproportionate number of skyboxes when compared to its modest 5,300 capacity. Not to mention sheer walls built immediately behind each goal.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán delivered the opening speech, before Sporting Lisbon faced off against MTK, a repeat of the same match-up in the replayed Cup Winners’ Cup final of 1964 – except that the Portuguese brought a reserve XI and MTK would soon be relegated.

This being Hungary, there was one final twist to the tale. Exactly a week before the grand unveiling, there was another: while testing out the big video screens, technicians decided to use a Hungarian porn film, one starring a notable Magyar actress in the genre. Somehow, the press was alerted to the story and delighted in broadcasting it to the nation.