A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

Could there be a better way for a club to celebrate its centenary than with a new stadium reflecting its heritage, a recent double win and a return to Europe?

Bankrupt and amateur in 2013-14, AEK Athens approached their historic milestone a decade later by attracting the biggest crowds in the Greek Super League, and full houses for the visits of Ajax and Marseille in the Europa League.

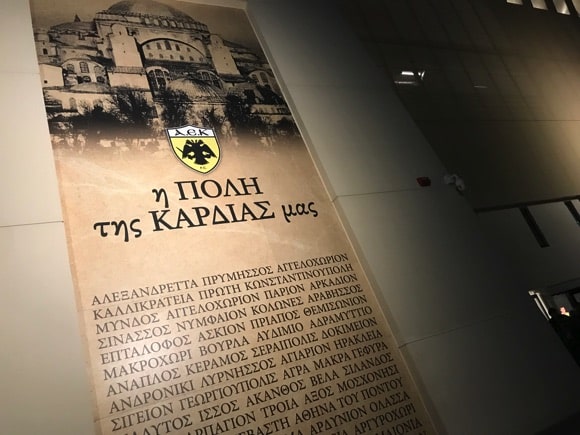

The venue selected to host the Europa Conference League final in AEK’s centenary year of 2024, the club’s Agia Sophia Stadium, is equally rich in symbolism. Guarded by the double-headed eagle of Byzantium, representing the Greek Orthodoxy once based in Constantinople, the stadium is named after the church built by the Byzantine emperor 1,500 years ago.

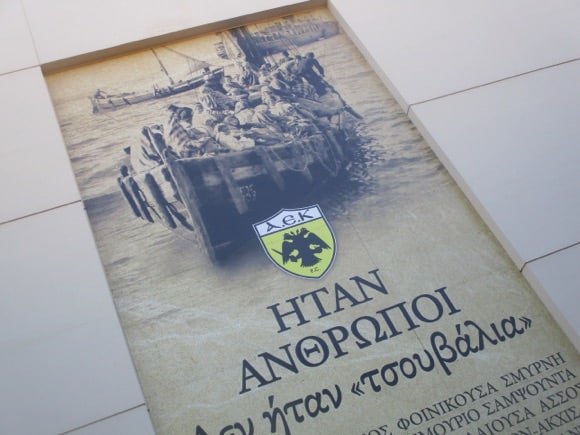

Converted into an Ottoman mosque, today’s Hagia Sophia is the most iconic sight in what is now Istanbul, Turkey’s biggest city, erstwhile home to hundreds of thousands of Greeks. Forced to flee in the 1920s, they re-established communities in pockets of Athens such as Nea Filadelfeia north of the city centre.

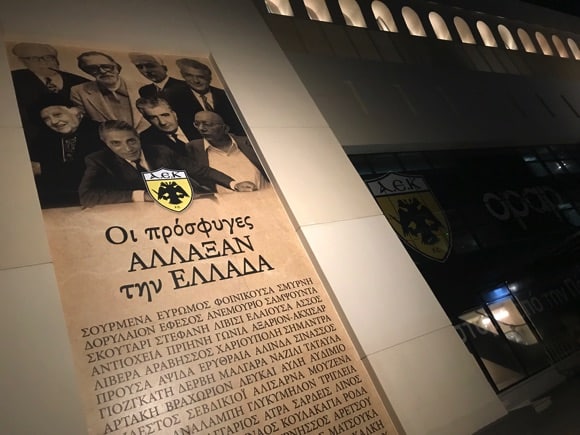

Among the refugees were well-connected entrepreneurs who had established sports clubs in Constantinople in the later 1800s such as Ermis, whose football team were known by local Greeks as Pera. Influential politician and journalist Konstantinos Spanoudis, along with leading members of Pera and its former counterparts Mégas Aléxandros, Iraklís, Olympiás and others, founded the Athletic Union of Constantinople, AEK for short, in Athens in 1924.

AEK were not the only refugee club in Greece: Apollon and Panionios, both from Smyrna, modern-day Izmir, continued their rivalry in Athens, but Spanoudis used his clout to lift AEK into what was already football’s Big Three in Greece. While Panathinaikos dominated the Athens Championship and Olympiacos the Panhellenic Championship, AEK lifted the first Greek Cup in 1932.

One of the winning goals came from Kostas Negrepontis who had won the Turkish Championship with Pera a decade earlier. He went on to coach AEK and the Greek national team on several occasions until the late 1950s.

Spanoudis duly built the AEK Stadium in 1930, on AEK’s training ground in Nea Filadelfeia, originally land assigned for refugee housing. This is also the site of today’s Agia Sophia Stadium. As AEK coach either side of World War II, Negrepontis oversaw the club’s first Panhellenic Championship titles just before the conflict broke out.

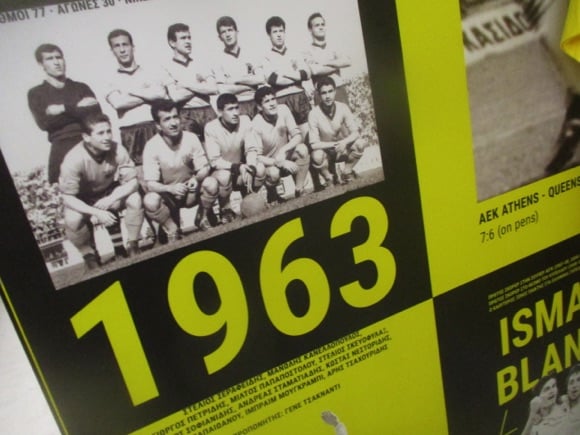

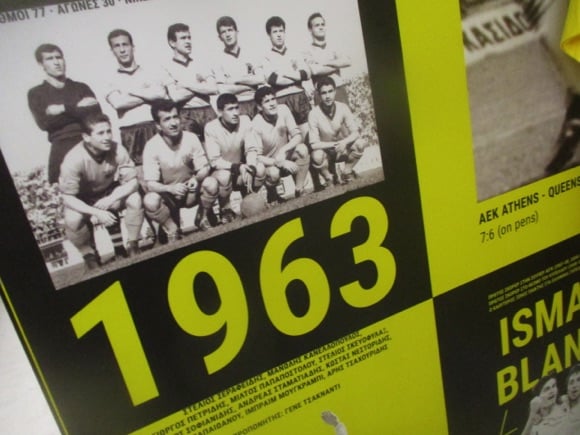

Negrepontis also spotted Kostas Nestoridis, an impoverished refugee from Drama, who came to AEK by way of Panionios in 1955 and hit almost a goal a game over the following decade. Top league scorer five seasons running, Nestoridis led AEK to their first post-war title in 1963 – won over Panathinaikos on goals scored – and ushered in the European era.

The season was also memorable for the arrival of Mimis Papaionnou, barely 20, later named the greatest Greek footballer of the century. Also a singing star responsible for the club’s anthem, Papaionnou would go on to win five league titles with AEK, including in his last season of 1978-79. His death in 2023 was marked with a moving ceremony at the newly opened Agia Sophia Stadium, whose predecessor he had graced for almost two decades.

The other key figure from this era is Nikos Goumas. A shipping mogul and Greek football patriarch in the classic mould, this AEK legend oversaw the modernisation of the club’s original stadium that later bore his name, arranging for the great Barcelona side of the early 1960s to take part in the curtain-raising fixture.

But AEK still lacked the spending power and regular domestic success of their two city rivals, Olympiacos and Panathinaikos – until the arrival of Loukas Barlos. A football man of the old school, this bauxite millionaire knew what he was doing when he brought in Czech coach František Fadrhonc, so steeped in the Dutch total football of the early 1970s he led the national side right up to the start of the 1974 World Cup finals.

Provided with a decent budget thanks to Barlos, Fadrhonc lifted defensive midfielder Giorgios Skrakis and prolific striker Georgios Dedes from Panionios. The first season under Fadrhonc, AEK pushed Olympiacos close for the title, scoring more and conceding fewer goals than any of their rivals.

Then came Thomas Mavros. Another Panionios man, he was barred from moving to AEK until Barlos engineered the move. Spearheading the club’s most gilded era, ‘The God’ was top league scorer both times when AEK won two straight titles in 1978 and 1979, the second time when Olympiacos refused to meet in a play-off.

This led to memorable victories in Europe, beating a decent Derby side in the UEFA Cup in 1976, and setting up a shock comeback at home to QPR, pulling back a 3-0 defeat in London to level the aggregate at a fervent AEK Stadium. Close to snatching the league title in England the season before, Rangers struggled to contain a rampant Mavros, whose brace helped take the tie to penalties. Twelve spot-kicks in, David Webb hit the post to set Athens alight. The late subbing of goalkeepers by Fadrhonc just before the final whistle proved decisive.

Reaching the semi-final to face the great Juventus of the 1970s, AEK were outclassed in Turin, holding the Italians to 0-0 at home until a late goal by Roberto Bettega ended the hosts’ most impressive European run.

Mavros played for another decade at AEK but Barlos was forced to bow out after running out of money – his own personal money, as he had been mortgaging his house. Still revered at AEK, he is honoured with a chapel in his saint’s name at the new Agia Sophia Stadium. After Barlos’ departure, AEK trod water until the return of Bosnian Dušan Bajević, who had paired up with Mavros as a fearsome strike duo for four memorable seasons.

As he had done as a player, the former Yugoslav international left his native Mostar for AEK to be coach – the most successful in the club’s history. Securing the title in his first season, a decade after the last one he had won as a player, Bajević brought in strikers Vasilis Dimitriadis and Alexis Alexandris in 1991 to dominate Greek penalty areas – and the top-tier Alpha Ethniki, conquered three years on the trot, each time with either striker heading the scoring charts.

In Europe, the last league title was followed by a first autumn in the Champions League after seeing off a Rangers side in their title-winning prime. Controversially, Bajević left for Olympiakos, though would twice return to AEK, first in 2002. Constant abuse from fans eventually forced him out, but not before he had achieved two high-scoring draws against Galácticos-era Real Madrid in a defeat-free campaign in the Champions League group stage.

Bajević had come back to an AEK Stadium, renamed after former president Nikos Goumas, in poor shape after the terrible earthquake of 1999.

In 2003, the decision was made to knock it down. AEK moved to Panionios, staging prestigious fixtures at the Athens Olympic Stadium. Finances remained precarious as ex-goalscoring hero Demis Nikolaidis stepped in to head a consortium of owners and achieved laudable results with precious few resources. Immediately after his departure in 2008, back came Bajević as coach and the club enjoyed two relatively stable years.

Physically attacked by ultras at a friendly game (!) in 2010, Bajević soon left AEK for the third and, so far, final time. AEK soon faced complete ruin, players leaving in droves even under the presidency of all-time hero, Thomas ‘The God’ Mavros. Filling in the gaps with youngsters, AEK were relegated, then declared bankrupt and given amateur status, dropping down two divisions for 2013-14. To the rescue came the club’s former centre-back Traianos Dellas as coach, and previous owner Dimitris Melissanidis as president, on the promise of regeneration and a new stadium, even though AEK were playing third-tier football before a few thousand in the 70,000-capacity Olympic Stadium.

Two promotions later, and AEK were not only back in the Super League but qualifying for Europe and winning the Greek Cup. Home was still the Olympic Stadium, where 50,000 gathered to see in a first league title in 24 years in 2018.

Under the returning Manolo Jiménez, who had initially replaced Bajević in 2010, Argentine loanee Sergio Araujo and Greek international Lazaros Christodoulopoulos had teamed up as a strike pair to take AEK on an unbeaten run from late October onwards. This included a controversial win over PAOK, whose late goal against AEK might have turned three points into six had it not been offside and a gun not been produced as PAOK protested.

All this time, recent president Dimitris Melissanidis was planning a new stadium that reflected AEK’s Byzantine heritage, bringing in Greek architect Athanassios Kyratsous to recreate the Hagia Sophia in Nea Filadelfeia, 1,000km from Constantinople.

Contractual difficulties meant that AEK failed to retain their title winning side the following season, marked by bitter clashes with PAOK, the attendance for the Greek Cup final between them limited to just over 1,000 invited spectators only.

As the pandemic slowed construction of the long-awaited Agia Sophia Stadium, AEK trod water before relatively low crowds at the Athens Olympic Stadium. When it was eventually unveiled in October 2022, more than 7,000 days after the closure of the Nikos Goumas, the league game with Ionikos was held up for 20 minutes just to clear the flare smoke from the pitch.

AEK had started the campaign poorly, playing two home games at Apollon’s ground of the Rizoupoli and losing one. But with former Argentine international Matías Almeyda in command, his compatriot Sergio Araujo hitting his stride and Mexican international Orbelín Pineda pulling the strings in midfield, AEK saw off PAOK and Panathinaikos at a packed Agia Sophia. Almeyda also galvanised underachieving Trinidadian international Levi García, whose brace against Olympiacos set up yet another Greek Cup final with PAOK.

Played behind closed doors in Volos, victory sealed a fairytale double for AEK, who had failed to qualify for Europe the previous season. Qualification for the Champions League in 2023-24 proved a bitter-sweet reward as ultras from Dinamo Zagreb and Panathinaikos attacked AEK supporters in Nea Filadelfeia, killing 29-year-old Michalis Katsouris. When the tie was replayed, two very late goals from Araujo and, ironically, former Dinamo centre-back Domagoj Vida, reversed the aggregate. AEK then fell to Antwerp in the Play-off Round.

The Europa League pitted AEK against Marseille, whose fans share a fraternal relationship. While the Mediterranean love-in between them made for some impressive tifos in both football-mad cities, AEK’s shock win at Brighton proved equally memorable, the Seagulls making their European debut 25 years after nearly disappearing entirely.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

It was a long time coming, 7,094 days to be precise, but any AEK fan will tell you that the Agia Sophia Stadium was well worth the wait. Going by the sponsor’s name of the OPAP Arena – owner Dimitris Melissanidis had interests in the Greek betting firm until 2022 – this 31,100-capacity football cauldron will host the Europa Conference League final in 2024, a century after AEK’s foundation.

For all of that time, the club has been rooted in Nea Filadelfeia – or rather, uprooted in this northern suburb, as AEK’s origins lie very much in Constantinople. This is why their stadium is named after the magnificent Byzantine church that is now the Haghia Sophia mosque in Istanbul, and why a double-headed Byzantine eagle greets AEK fans milling outside the ground. Behind it, the Orthodox chapel of Hosios Loukas – honouring former club president Loukas Barlos – sits between a traditional Greek shoemaker’s and an OPAP betting bar.

This harking back to AEK’s Byzantine past is also reflected in the large posters that decorate the exterior, images of Greek refugees fleeing modern-day Turkey, set against the Walls of Constantinople in football stadium form. This was the brief given to Athanassios Kyratsous, the Greek architect’s long years working in restoration of historical sites in Italy put to good use here.

Surrounding the ground, cafés and restaurants throng with people pre-match, fans trekking from all over Greece on family pilgrimages to AEK. With an average home attendance in the upper 20,000 range, the call-and-response chants from either goal, the ultras in sectors 20-23 at one end, and 41-44 in the other, echoes round the stadium all game. Visiting supporters allocated top-corner sectors 46 and 48 have prime views of AEK ultras Poznaning at the opposite end, and of the pre-match laser show.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

From Athens city centre, take green metro line 1 to Perissos. When you arrive, use the underpass to walk under the tracks, across the traffic lights and head straight along Alexandrou Papanastasiou, keeping a construction site to your right. After 5mins, bear right at Smirnis or the next one along.

The route will be lined with vendors hawking AEK souvenirs and snack vans.

Trolleybus 3 runs from the city centre to Nea Filadelfeia, stopping at café-lined Fokon by the stadium but match days mean diversions and traffic jams.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Tickets are best sourced online through the club, for home games two or three weeks in advance. Note that most matches are played close to capacity, so leaving everything to the last minute means that availability might be limited to the €100+ seats over the halfway line, in sectors 8/10 and 31/33.

If any General Admission tickets are on offer, this allows you entry in the home end for around €60.

If money isn’t an issue, you can also try the ticket offices at the stadium in the run-up to match day. For all enquiries, contact tickets@aekfc.gr.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

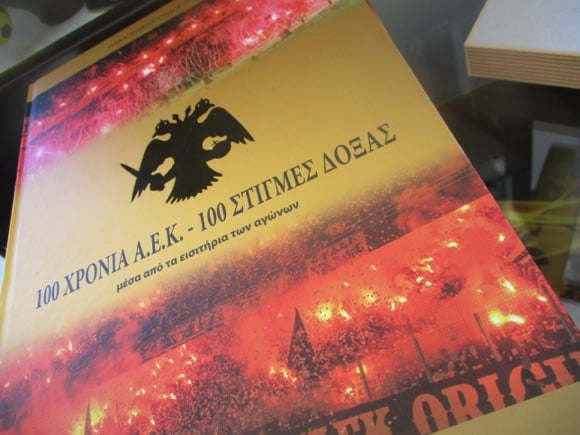

An orderly queue forms outside the AEK FC Store (Mon-Sat 10am-6pm, match nights), tucked inside the main entrance, the yellow-and-black merchandise including candles, ceramics and retro bar scarves. Famous past managers and presidents are displayed across one wall, while the club’s history outlined in a large centennial album.

The current second kit is pure black, the third choice bright orange, both with ‘AEK FC’ emblazoned on the back of the neck.

If you’re wandering around the city’s historic centre, you’ll find an AEK outlet at Aiolou 7, the Black & Yellow Store (Mon-Sat 10am-10pm, Sun 10am-9pm), alongside the ruins of Hadrian’s Library.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

AEK is surrounded by cafés and restaurants, their terraces filled to the brim on match days. The hub of this activity is the junction of Fokon and Leof Dekelias, marked by bar/kebab restaurant I Poli and Pasatempo opposite, aka the ThiRio pub, its multicoloured chairs making it look like a Mexican restaurant instead of the rock-focused bar it aims to be.

Beside I Poli, if you’re just after a quick bite, the Theios Fanis bakery has been in business since 1970, father and boy serving pies to AEK fans – beneath a huge image of Thomas Mavros celebrating yet another goal, Mixail will talk you through the many cheese varieties on offer. Beside Pasatempo/ThiRio, Joga is more a café but the many gathered on the terrace can also sink a beer or spirit.

Round the corner, the Eleven bar shows football action on its big screens, patrons watching over beer or a shisha pipe.

Back on Leof Dekelias, Kitrini Gkazoza typifies the rather bland trendy café/restaurants in the vicinity, its terrace filled with AEK fans pre-match. Next door, the recommended Skantzoxoiros attracts music-obsessed regulars of a certain age, a real bar where serious drinkers glug beers in rapid succession as kick-off approaches. While much of the contemporary AEK experience is a world away from the punk/anarchist days of the 1980s, ‘The Hedgehog’ is the nearest thing to it in the 2020s.

Further along Leof Dekelias, black-and-yellow branded Nea Vyzandini Gonia is where you need to be – and where you’ll find everyone else. Waitstaff in tops bearing the message ‘In Almeyda we trust!’ deliver logo’d glasses of Vergina beer to the AEK multitude on the heaving terrace and around the bar interior-cum-club museum. Archive photos, retro shirts of various opponents and match posters from yesteryear line the walls. TV screens and table football provide entertainment.

There’s also a busy scene around the stadium concourse. The twin terraces outside two standalone houses facing the ground fill from long before kick-off – look out for the Mamos beer awnings – while stadium bar O Vosporos opposite is equally lively. Just inside the main entrance, OPAP doubles up as a betting shop, screens surrounding the island bar.