On Tuesday, England take on Costa Rica in Belo Horizonte. The setting has a certain resonance, for it was in this regional capital of south-eastern Brazil that England suffered their most ignominious defeat the last time the World Cup was held here. Their 1-0 defeat by the USA in 1950 is arguably the biggest shock in the entire history of the tournament. Dave Lange, a soccer expert from the city that provided half the US team, St Louis, takes up the story.

Belo Horizonte, where England play Costa Rica on Tuesday, is where Roy Hodgson’s predecessors suffered the most disastrous World Cup defeat in their history.

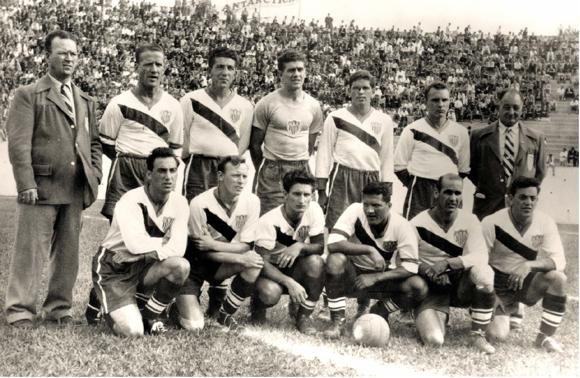

In 1950, a side that featured Tom Finney, Billy Wright and later England manager Alf Ramsey sensationally lost 1-0 to a little-known team from the USA.

But who were these men who ruined England’s competition debut? Where did they come from?

The answer is, mainly, St Louis. Five of the starting XI on that fateful afternoon of June 29 came from St Louis.

If ever a World Cup squad was destined for disaster, it was the USA in 1950.

Eliminated 9-0 by Italy in their only match at the 1948 Olympics, the USA went to Brazil under a cloud of dissent. US Soccer Football Association president Walter Giesler had included six from his home town of St Louis in the squad. One player from New York, Jack Hynes, was dismissed when his private protests about the player selection process made the newspapers.

Ironically, it would be the St Louis contingent who helped the USA to one of the most colossal upsets in World Cup history.

Mostly ignored in the USA at the time – there was only one American reporter there, Dent McSkimming of the ‘St Louis Post-Dispatch’, who had to take time off and pay for his own trip to Brazil – the game received its due in 1996 with the publication of a slim book called ‘The Game of Their Lives’ by Geoffrey Douglas. Although only brief snippets of match footage exist, the book reconstructed the match almost minute-by-minute, apparently relying heavily on the remarkable memory of Harry Keough, USA’s right-back from St Louis.

The book led to a flawed film that failed to earn much acclaim or revenue when released in 2005. Asked his opinion of the movie, Keough famously replied with one sentence: ‘They got the score right’.

Until the book, myth and mystery surrounded Belo Horizonte 1950. The USA were derided as amateurs of dubious nationality. The USA were also described as fantastically lucky, saved by the Belo Horizonte goalposts, their legend in World Cup lore sealed by a misplaced effort credited to centre-forward Joe Gaetjens.

Yes, the Americans enjoyed good fortune, and England, who rested Stanley Matthews, underestimated them. But on closer inspection, the USA had a level of quality that accounted to some degree for the surprise outcome.

Five of the St Louis contingent were drawn from Simpkins Ford, who had won the US Open Cup (America’s version of the FA Cup) in 1948 and 1950. One of them, Gino Pariani, was due to be married during the tournament but rescheduled and tied the knot before the trip to Brazil. Simpkins forward Frank ‘Pee Wee’ Wallace had fought in World War II and was captured by the Germans after escaping his burning tank at Anzio. Simpkins goalkeeper Frank Borghi, a giant of a man with a gentle temperament, was a medic with an infantry unit and nearly died in the Battle of the Bulge. A buddy put a round ‘right between the eyes’, in Borghi’s own words, of a German soldier who had taken aim at him. Charlie Colombo, a centre-back from Simpkins, was, like Pariani, a former Missouri Soccer Association Player of the Year.

Keough, the lone St Louis player not with Simpkins, is a legend in the US game, integral to one Open Cup victory and six consecutive US Amateur Cups. Philadelphia’s Walter Bahr, like Keough, stands tall in the US Hall of Fame. Ed McIlvenny and Joe Maca played in Europe’s lower divisions before emigrating to the US. Ed and John ‘Clarkie’ Souza, though unrelated, both hailed from Fall River, Massachusetts, then a hotbed of soccer. Some of Clarkie Souza’s teammates considered him the most skilful player on the US team.

Gaetjens, sometimes dismissed as a lowly dishwasher in Harlem, in fact had come to New York from Haiti to study accounting. Although he did work in a Harlem café, he was from a well-to-do Haitian family. He was known as ‘a guy who had a nose for goal’, as Bahr said in 2010.

A key element to the US performance was the relationship between Bahr and Keough. ‘It cannot be overstated how critical to team unity the immediate rapport was between my Dad and Walter Bahr,’ said Ty Keough, himself a US international midfielder 30 years later. ‘The group was ripe for a factional skirmish between the East Coast group and the St Louis contingent. The respect between these two men cemented a team approach to the challenge.’

Shortly before the tournament, this US side played a send-off friendly in New York against an English FA XI, an all-star team of squad and fringe players including Sir Stanley Matthews. The visitors struggled to win 1-0.

Further evidence came in USA’s World Cup opener with Spain. The Americans were ahead with 12 minutes to play when Colombo lost the ball and Spain scored the first of three times. Bahr later said it was the USA’s best performance of the tournament. US scorer Pariani saw it differently. In later years, Pariani told his son that the non-St Louis players had refused to pass him the ball after the goal.

Colombo, who once said he would ‘do anything to win’ – and that was during a local amateur softball game – would not repeat his late-game mistake in the next match in Brazil. A defender who provoked verbal and physical mayhem (and wore gloves to prove it), Colombo set his sights on shutting down England centre-forward Roy Bentley. ‘I couldn’t play centre-back as well as Charlie’, Keough said in 2010, two years before his death, ‘because Charlie was… well, Charlie was brutal’.

Colombo’s moment came late against England. By that time, the heavy favourites were scrambling to overcome a 37th-minute opener by Gaetjens, the man with a nose for goal. He may have used his nose as he dove, just getting some part of his head to a shot from Bahr, and redirecting it into the net.

The USA were just eight minutes away from victory when Stan Mortensen broke through, honing in for a one-one with Borghi.

Colombo caught up from behind and executed a flying tackle to bring the Englishman down just outside the box. Colombo, who hailed from an Italian neighbourhood of St Louis, said afterwards that the Italian referee congratulated him in Italian after giving a foul rather than a dismissal.

Jimmy Mullen headed the subsequent free-kick past Borghi. The St Louis goalkeeper, who had made countless saves throughout the game (and was aided by at least four shots against the woodwork), reached behind him and batted the ball out before it completely crossed the line. Keough, who credited Borghi as the difference in the match, called the keeper’s acrobatics for Mullen’s header, ‘one of the greatest saves you’ll ever see in your life’.

While England dominated the match – outshooting the USA 14-2 in the first half alone – Gaetjen’s goal was not the only scoring chance the Americans had. After Gaetjens had headed the ball just over the bar in the second half, late in the game, Pee Wee Wallace drew out Bert Williams, England’s goalkeeper, and shot at an empty net from close range. Alf Ramsey slid across and cleared the ball just before it crossed the line.

Carried off the field by some of the 10,000 delirious Brazilians on hand – some accounts claim as many as 30,000 were there – Borghi smiles at his memories of that long-ago day. ‘I thought the roof was coming off the place,’ he said later.

England, in dark blue that afternoon, never wore those colours again.

Perhaps drained by the epic match, neither side regathered its strength in subsequent matches. The USA would be eliminated by Chile, and a deflated England suffered the same fate against Spain.

No fanfare greeted the US players upon their return. In a typical homecoming, Keough was met by his father at the airport in St Louis and then boarded a bus to play at a softball tournament in Peoria, Illinois. That autumn, many returned to playing in the local soccer leagues from whence they came. ‘We made $6 a game if we won, $4 if we tied, and $2 if we lost,’ Keough said.

Decades passed before they were honoured. Finally, the entire USA squad, substitutes included, was elected to the US Soccer Hall of Fame in 1976.

Sixty-four years after the match, all but two of the USA’s starting XI have passed on.

The first to go was Gaetjens, the dishwasher in Harlem turned goalscorer in Belo Horizonte. He disappeared in his native Haiti in 1964 during a reprisal against his family for its opposition to dictator ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier. It is assumed he was shot or died from hardship in prison.

Hard man Colombo turned down a pro offer in Brazil and died from cancer in his Italian neighbourhood in 1986. Wallace, from the same part of St Louis as Colombo, died in 1979. Pariani, who had had to move his wedding day to go to Brazil, told his son that the whole affair so disappointed him that he rejected all subsequent invitations to play for the USA. He continued to play locally for many years and died in 2007.

Maca played briefly in his native Belgium after the 1950 World Cup, returned to the US, gained his citizenship, and died in Massepequa, NY, in 1982. Ed Souza represented the US through to 1954, 25 years before his death. McIlvenny, born in Scotland, moved to England after the World Cup, made two appearances for Manchester United, and played for other teams in Ireland and England, where he died in 1989. Keough, a USA mainstay until 1957 and a coach of five national collegiate champions at St Louis University, and Clarkie Souza, the only American picked by a Brazilian newspaper in an all-star team after the tournament, died 33 days apart in 2012.

Bahr, 87, and Borghi, 89, are the last standing. Bahr, who became a lifelong close friend of Keough’s, was a USA player until 1957 and a successful college coach at Penn State. Borghi, who ran a funeral home in the Italian neighborhood of St Louis that spawned four of the 1950 XI, is a minor celebrity who gets fan mail from overseas. ‘They send pictures and ask me to sign, but they don’t send any money to pay to mail them back,’ Borghi said. ‘One guy, though, did put in a dollar.’

Dave Lange is author of ‘Soccer Made in St Louis’, a history of the game in America’s first soccer capital. More details can be found on his website, soccermadeinstlouis.com.