Long-delayed project recently unveiled features stunning visuals but is light on detail

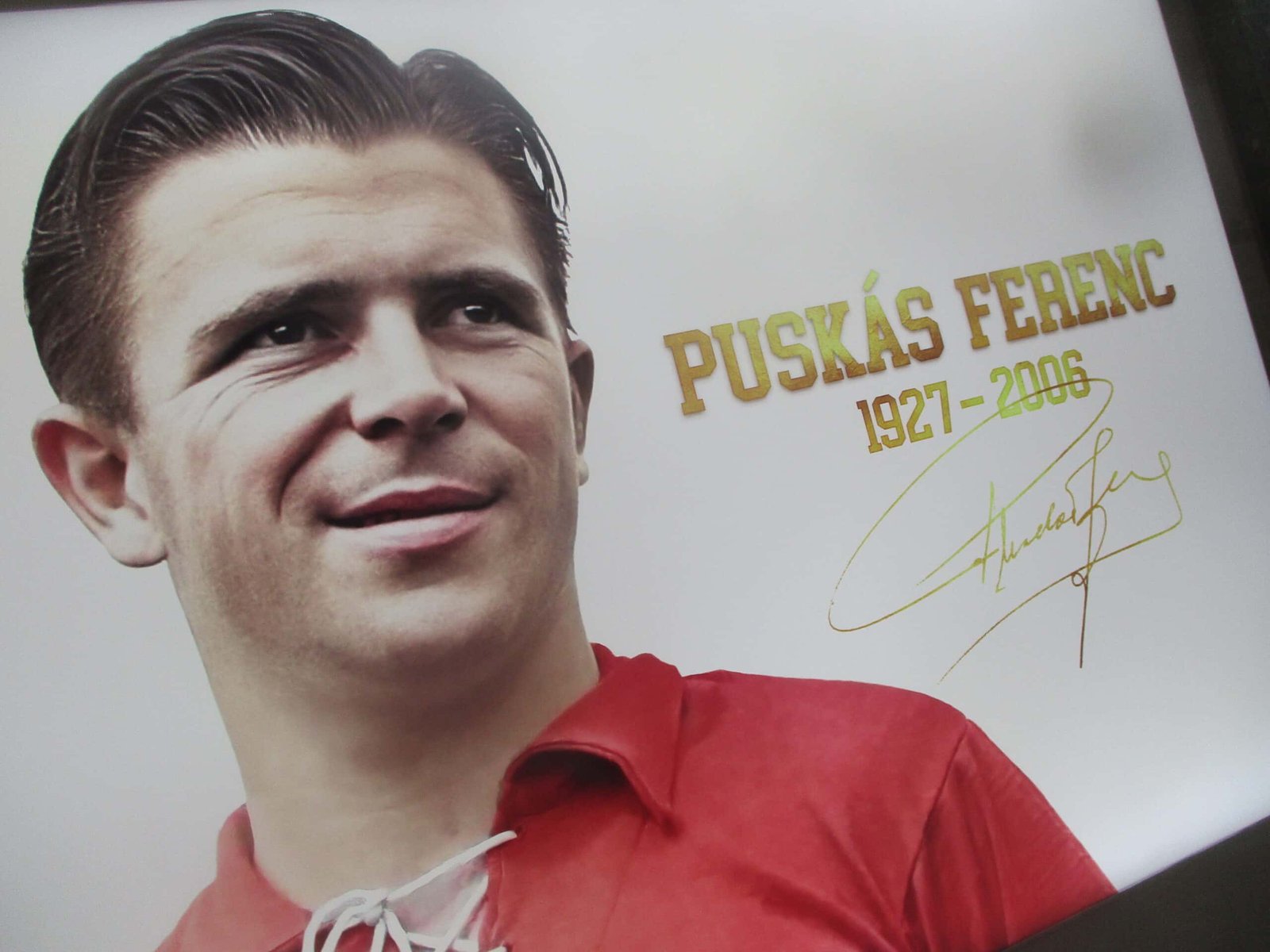

A stage play, statues, films, books, murals – and now his own museum. All-time Hungarian football hero Ferenc Puskás has recently been honoured in Budapest with a four-floor presentation of his life and times, set in the last remaining feature integral to the national stadium he graced back in the 1950s.

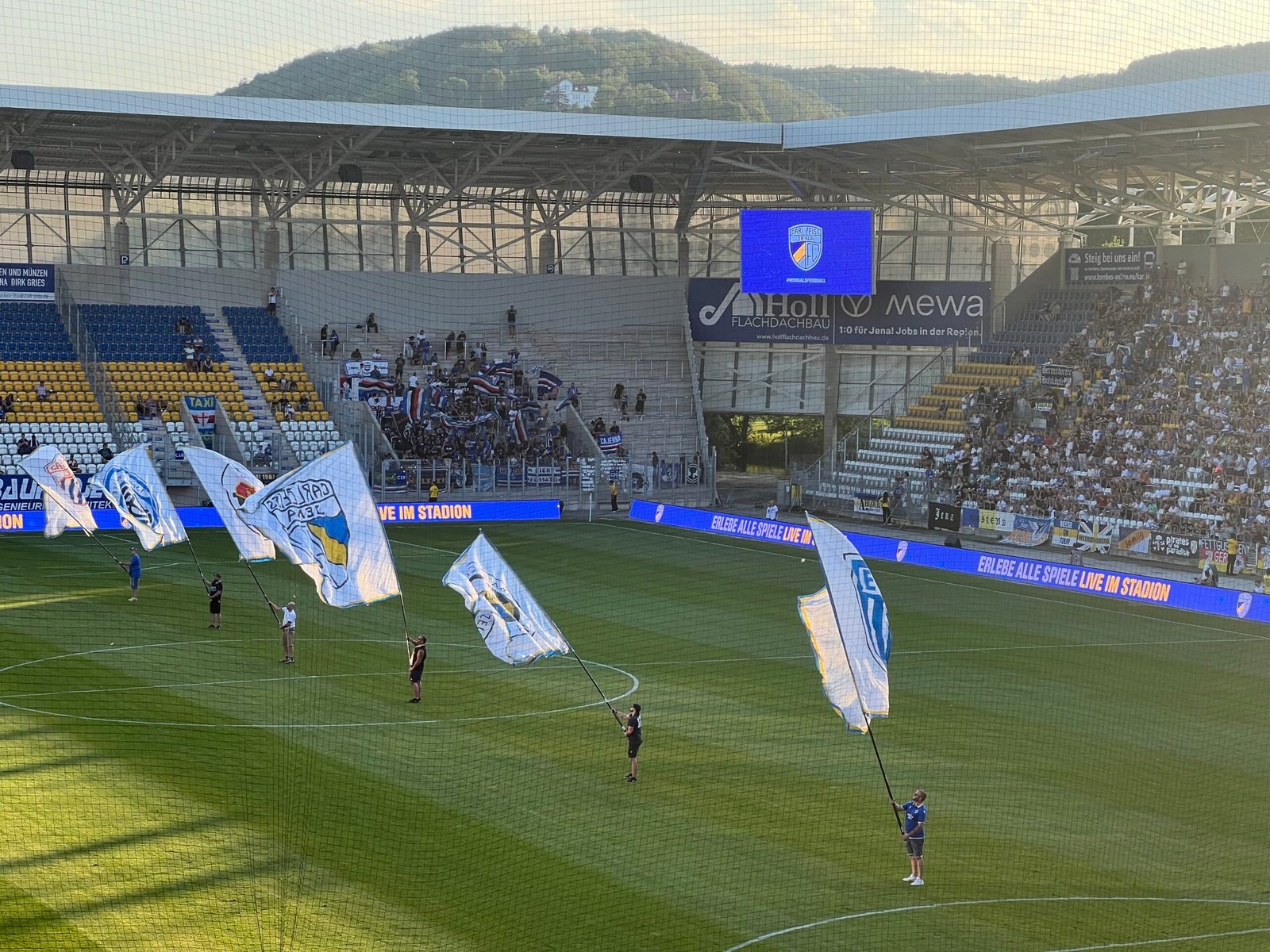

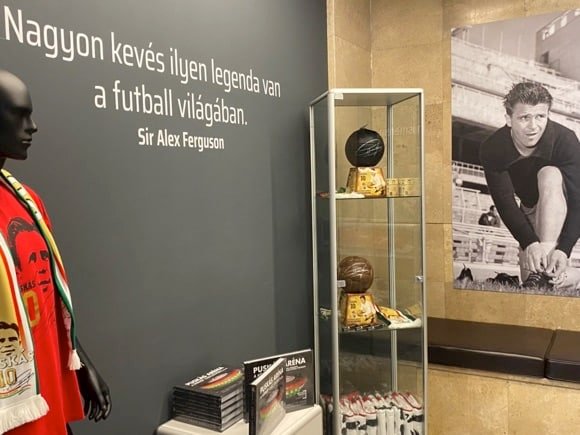

Reconstructed and reopened in 2019, the now named Puskás Aréna incorporates the tower through which leaders and dignitaries once passed on their way to the VIP area of the former Népstadion. Its legacy and location have allowed the museum designers to make use of this Communist-era time capsule and grant visitors the chance to look into the new arena for snaps and selfies for a modest supplement to the €10 entrance fee.

It also presents the authorities with an eternal dilemma. How to glorify Puskás, whose state funeral in 2006 took place at the nation’s sacred Basilica in the heart of Budapest, without aggrandising the Socialist régime which built the Golden Team he starred in, the Magic Magyars of 6:3 legend? And, in fact, built the original stadium itself?

While there is no doubt that Puskás had little time for political theory, and made the life-changing decision, as did key teammates Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor, to stay in Western Europe after the failed anti-Communist Uprising of 1956, the one-party system helped create the Golden Team, Hungary’s best players corralled into one club, Honvéd.

Under the command of Communist-leaning manager Gusztáv Sebes, these players developed and interacted with each other as one unit, week in, week out. They were also the perfect poster boys for Communist Hungary, the red star and hammer-and-wheatsheaf emblem emblazoned on those cherry-red or red-white-and-green banded shirts. Puskás and company were even photographed lugging wheelbarrows of bricks to help construct this very tower and the Népstadion, the People’s Stadium, around it.

In turn, some 70 years later, the deification of Puskás in statue, museum, stadium and stage play form feeds into a narrative followed by the present-day Hungarian authorities, virulently anti-Communist and completely spendthrift where 30 new and/or rebuilt football stadiums are concerned.

Exiled from Communist Hungary to become a global star at Real Madrid, then returning to see out his last 15 years in Budapest, Puskás is the definitive Magyar hero, banished by a Socialist dictator, defiantly triumphant on the world stage.

It was logical, therefore, that these authorities should look to Mária Schmidt to create the Puskás Museum. A main force behind the House of Terror, the chilling collection of artefacts related to the imprisonment, torture and execution of victims in Socialist-era Hungary, Schmidt has made the subject matter her profession and is adept at handling big-budget projects of national importance.

For the long-delayed Puskás Museum, as head of the Public Foundation for the Research of Central and Eastern European History and Society, she had a sum just shy of four billion Hungarian forints (almost €10 million) at her disposal.

After their successful collaboration on the visually stunning House of Terror, it was also logical that Schmidt should turn to award-winning designer Attila F Kovács. Having worked with Oscar-winning film director István Szabó and designed opera sets in Vienna, Kovács is a visual genius. No doubt it was his idea to use the iconic scoreboard and clock from the Népstadion to display admission prices behind reception.

The first floor of the museum, the only one of the four that deals solely with Puskás the footballer, is a work of art and worth the €10 admission alone. Pillars of images from his life and career spin around a large exhibition space bordered by four corners, each a mock-up of the player’s main abodes.

As you peer each one, snatches of particular songs or contemporary commentary waft over from the radio, just if you had walked in on him and his loved ones. First comes impoverished Kispest, where Puskás grew up with a footballer for a father and best mate József Bozsik of the Golden Team for a neighbour. As his status grows between 1954 and 1956, Puskás and his young family acquire a nicer lodging in the leafy Zugló district of Budapest.

Spanning the whole of the back wall, a lovely photograph depicts Puskás kissing his little daughter Anikó. Given the lack of any documentation across the museum, except for the occasional stand-out quote in Hungarian used for dramatic effect, the non-Magyar initiate might take this to illustrate Puskás the family man.

Many Hungarian visitors, however, would understand immediately that, given the end date of the player’s upscale sojourn in Zugló, this is what Puskás left behind when he made his fateful – and potentially disastrous – decision not to return to Hungary after the 1956 Uprising was brutally put down back home.

Days later, his wife, the loyal Bözsi, needed four attempts to cross the border into Austria on foot, carrying their four-year-old daughter with her, risking both their lives. Those who hire an English-speaking guide may be given these snippets of information by a knowledgeable member of museum staff – the exhibition otherwise badly needs a downloadable audioguide in English, surely not beyond the remit of an original budget of nearly €10 million

The third corner is dedicated to the player’s time in Spain, rapid-fire Castilian coming over the airwaves amid all the furnished trappings of a content Madrileño lifestyle. This, you would imagine, was where the Puskás family was happiest, Anikó growing up bilingual and a busy social life dispelling pangs of homesickness.

The fourth and last room depicts their permanent homecoming after the fall of Communism, a flat in Budapest’s prestigious Castle District, Puskás pictured with his two grandchildren.

The next floor focuses on the Golden Team, each member shown individually in action against a gold backdrop, outfield players dressed in Hungary’s mainly white second kit for better effect. A video loop with Hungarian-only commentary presents each one in turn, explaining their position, their key assets and a brief bio, rounded out by comparisons with later international stars in the same role and tips for young players today.

As if in a spaghetti Western, each is also shown by their nickname, or provided with one, manager Sebes being ‘The Master’. Sadly, Márton Bukovi, who did so much to develop the 4-2-4 system with Nándor Hidegkuti the deep-lying centre-forward, is pretty much left out of the picture.

Around the stark white room, centrepieced by a trophy presented to Puskás on his 75th cap, citations in Hungarian reflect the footballing wisdom of Camus and Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano (“Only Churchill used his head better than Sándor Kocsis”).

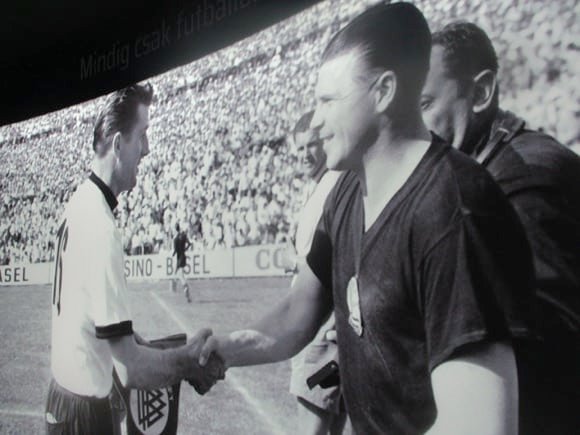

Puskás is quoted as saying that his most important goal – of nearly 600 – was the third against England in the 6:3 game. The drag-back also gets its own special section in the short video film broadcast in a little screening room.

Next comes a whole floor entirely dedicated to Communism in Hungary, the shortages, the repression and the brutality, culminating in the Uprising of 1956. It is suggested that the protests in Budapest after the defeat in the World Cup final of 1954 were the precursor to the ’56 Uprising, a theory often posited. Judging by the spread of evidence on offer here, Hungarians had more than enough hardships to deal with – a Welsh linesman’s flag ruling out a late Puskás goal in Switzerland would surely have been the least of their worries.

Given the lack of documentation, for the average football fan, the emphasis placed on the ills of post-war Hungary will be confusing – would a George Best museum have an entire floor dedicated to the Troubles? Probably not.

Things feel even more off-kilter when you reach the fourth and final floor, which is almost entirely given over to a pretty unspectacular Fiat car gifted to Puskás by an Italian sponsor in his early years of exile. The switch is now to southern Europe, the style, the extravagance and the pop tunes.

Behind reads a lovely anecdote about Puskás meeting fellow Magyar exile Miklós Horthy, the Hungary’s right-wing head of state between the wars, and an anathema to the Communist authorities back in Budapest but again, unless you’re a Hungarian speaker, you’ll never know what was discussed around the roulette tables of Estoril.

Those purchasing the €3.75 supplement can then climb another level for that bird’s eye view within the Puskás Aréna. Between floors, wall-to-wall displays of microfiche text, the kind spies preferred in the Cold War, present narrow strips of information – it’s only when you scrutinise them that you realise these are the microscopic details of every match Puskás ever played.

Equally, original artefacts from his life, boots, trophies, mementoes, are displayed in illuminated cubes that glide past you on a pulley system, but whether those studs were the ones that dragged the ball back at Wembley that foggy November afternoon of 1953, you’ll never know.

Famous footballers of the era stare out from the walls of the staircase, along with leading figures from Puskás’ life. Emil Östreicher, for example, player, manager, arranger, fixer, go-between, one of the most colourful characters behind the scenes in the 1950s, the man who had the foresight to bring an overweight Puskás to Santiago Bernabéu at Real and help transform the player from disgruntled has-been to superstar, has been allocated a portrait – but little else.

Pivotal to two of the greatest teams in the history of the game, Ferenc Puskás also had the most fascinating life of almost any footballing superstar, with the arguable exception of Maradona. There’s an almost equally fascinating museum just begging to be created about him. This isn’t it – but do go for the visual treat of his life story in photo, film and furniture form on the first floor.

Puskás Museum, Istvánmezei út 3-5, Budapest 1146. Open Tue-Sun 10am-6pm (last entry 5pm). Admission Ft4,000/€10, seniors & students Ft2,500/€6.20. Stadium view supplement Ft1,500/€3.75. Guided tours of the museum and Puskás Aréna stadium tours also available.

To find out more about the Honvéd side of the Puskás era, visit the Kispesti Futball Ház (Fő utca 38, Budapest 1191; tram 42 to Templom tér from M3 Határ út; open Mon-Thur 4pm-7pm). Run by friendly enthusiasts who will happily show you round, it’s a fascinating trove curated with genuine affection for the club and its surroundings.