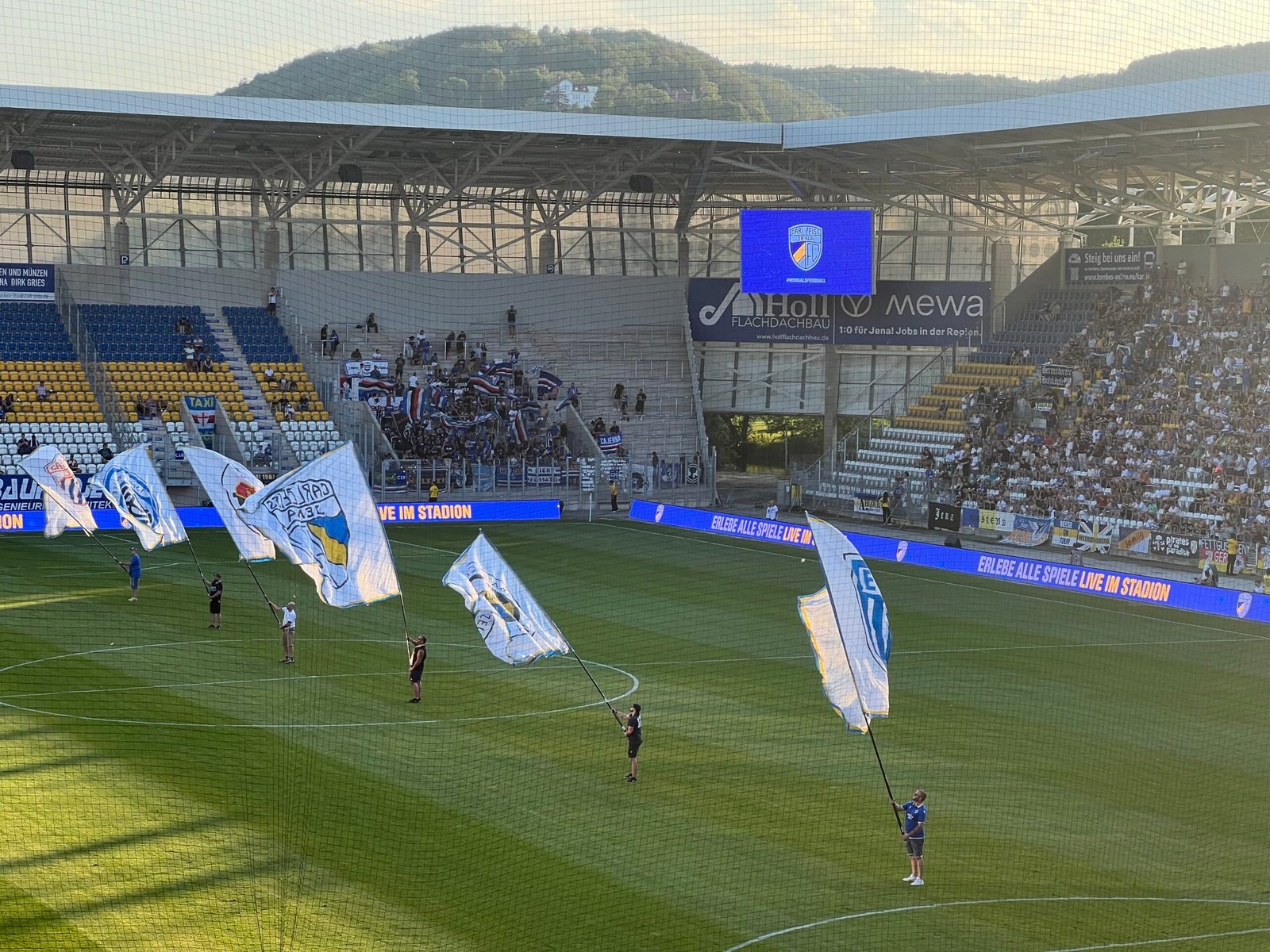

Despite February announcement of demolition and a rebuild, unloved stadium remains

In February 2024, Dinamo Zagreb announced that the club had reached an agreement with the relevant authorities for their Maksimir Stadium to be demolished and a new one built in its place.

So far, so good, many would have thought, as this long-running saga not only affects Croatia’s record champions but also the national team, for whom this ugly duckling of a football arena is also their de facto home.

The original Maksimir, opposite the long-established park of the same name at the eastern end of Croatia’s capital, was built in 1912. The then dominant club, HAŠK, bought land from the Church – a powerful body in Catholic Croatia – to construct what was then the finest football ground in the land, with a main stand holding 6,000 spectators.

The facility was later attacked by high school pupils who refused to be separated on ethnic grounds by Croatia’s new Fascist authority, the Ustaše, at a public event in 1941. Like many controversial episodes during this period, such as the so-called ‘Match of Death’ in Kyiv, its complete veracity cannot be proven, but this didn’t prevent the later Communist authorities from seizing upon it to demonstrate the palpable evils of Fascism.

Whether the stadium was burned to the ground in righteous anger by students armed with explosive chemicals in a mass protest, as dramatised in the 1977 Yugoslav film Akcija Stadion (‘Operation Stadium’), or just set light to, the fact is that when Tito dissolved Zagreb’s pre-war clubs to create Dinamo in 1945, he also had his architects rebuild the Maksimir.

(This was also when its wooden stands were transferred to the city’s second stadium, the Kranjčevićeva, meaning the anti-Fascist destruction of 1941 may not have been as devastating as Tito would have had us believe.)

Nonetheless, stand by stand, floodlight pylon by floodlight pylon, the Maksimir became a suitable home for Dinamo and Yugoslavia through the 1960s to the late 1980s.

Once Croatia split to set up its own post-Yugoslav league – a brutal process that may have begun here during a riot between fans of Dinamo and Red Star Belgrade in 1990 – then the Maksimir was always an oddity.

First, the host club was briefly forbidden from using its Tito-tainted name of Dinamo, a foolish state dictat that irked its ever-irkable following, the Bad Blue Boys. Secondly, while Croatia made their impressive entrance onto the world stage in 1998, Dinamo ruled a weak domestic league whose average crowds were in the low thousands. Zagreb needed a national showcase as well as a ground suitable for the visits of Slaven Belupo and Cibalia Vinkovci.

An initial renovation of this Socialist relic in 1998 upped capacity to 38,000, ten times the league average at the time. With regular boycotts from the Bad Blue Boys over some dispute or other, the Maksimir was not only quite empty, it was unloved. Despite this, Croatia still put in credible if failed bids to co-host the Euros.

A radical proposal for a new 60,000-capacity Maksimir came in 2008, the location not here but in the district of Kajzerica over the Sava. It fell on stony ground. Then, as gleaming arenas, malls and complexes were changing the face of Croatia’s once quaint capital, ambitious schemes for a retail and business hub centrepieced by a new-look Maksimir seemed to fill the front page of Sportske Novosti every month.

In 2019, Dinamo, now regular competitors in the Champions League, announced the demolition of their home since the 1940s but still sought a final agreement with the City of Zagreb. Soon afterwards, as pandemic restrictions came in, Zagreb was hit by a terrible earthquake, which closed the stadium’s East Stand.

(Anyone at a Dinamo game here in 2019 would have noticed a distinct lack of spectators in any case, following another BBB boycott.)

Therefore, in February 2024, when Dinamo declared the imminent demolition of the Maksimir and creation of a new arena, it was welcomed with huge relief all round. Not only was the suggestion credible, it followed a joint resolution between the City, the national government and the Zagreb Archdiocese, which still had a claim on the land that Tito was only too happy to gerrymander back in ’45.

However… the news came months after the mayor announced the reconstruction of the Kranjčevićeva, where Dinamo would have to play during the Maksimir rebuild.

Since February, there has been very little movement at either location. Certainly, no cranes surround either ground, as the tender to work on the Kranjčevićeva was granted but then disputed. No new Kranjčevićeva, no new Maksimir.

Perhaps worse, the Church still seems to be negotiating on recompense or return of its land, recompense involving sites for new churches elsewhere in town. Knowing that Dinamo and the City cannot start work without this agreement in place, the Church can drive a hard bargain.

Meanwhile, although the Dinamo board has perused the new stadium proposal, the public remains in the dark. It is even rumoured that the site won’t be the Maksimir at all – thus removing the Church’s bargaining chip – but elsewhere (where?) in a city that has seemed to have used every available space for yet another hotel or mall.

Given that the reconstruction of the crumbling Poljud in Split is also a bone of contention, it must seem an anathema to Croatia’s footballing authorities that the country’s most modern stadium, the new-build Opus Arena in Osijek, where the national team played its most recent international in September, was part-financed by the Hungarian government.

This Saturday, Croatia host Scotland in Zagreb, in an uncovered ground with only three working stands and a 60% probability of rain the day before. Will there ever be a new Maksimir?