The meeting of Dynamo Berlin and Lichtenberg opens old divisions – reports Alan Deamer

Before Twitter, fans didn’t vent their frustrations online – they acted. Take Erich Mielke. In December 1967, in the bitter depths of the Cold War that had divided the city around him, the head of East Germany’s hated Secret Police, the Stasi, had watched his team Dynamo Berlin lose 1-0 to Lichtenberg 47 from his office window overlooking the Hans-Zoschke-Stadion. Furious, he demanded its demolition on the spot.

Though surrounded by the Stasi headquarters in the heart of East Berlin, the stadium remained untouched, a testament to the resilience of the Lichtenberg community and, equally, to the bureaucratic hurdles required to relocate the club and/or repurpose the ground.

Instead, the authorities loaded the dice in favour of Dynamo, press-ganging quality players from the provinces and influencing referees to allow Mielke’s favourites to win ten GDR titles on the trot and earn the nickname of the Schiebermeister, the ‘Cheating Champions’.

Just as the sobriquet has stuck, so the Hans-Zoschke-Stadion still stands proudly opposite what is now the Stasi Museum, where a series of talks during Euro 2024, EM in der Stasi-Zentrale, explored the issues arising from Lichtenberg’s unique geopolitical topography within the GDR.

Fußball im Hinterhof der Stasi, ‘Football in the Stasi’s backyard’ is also the title given to the information boards lining the entrance to the stadium, detailing the complex background to post-war Lichtenberg.

A time capsule of football’s unpolished, no-frills charm, the Hans-Zoschke-Stadion is home to a club currently top of its division in Germany’s fifth-tier Oberliga. With the winter break upon us, Lichtenberg 47 have only lost once all season: 5-0 to Dynamo in the Berlin Cup last October.

This Saturday, January 18, the two clubs meet again in what might be termed a friendly. While the notorious Weinroten sit a league above Lichtenberg in the Regionalliga Nordost, their mid-table status and 47’s blemish-free push for promotion should see the East Berlin rivals cross paths once more in 2025-26.

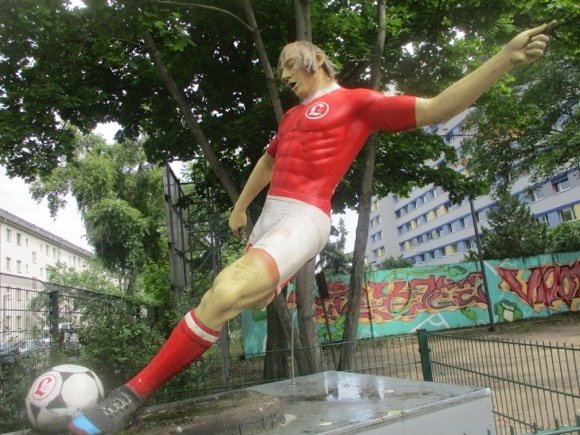

The origins of their relationship can be gleaned from the first signboard at the stadium, beside the statue of Tim ‘Schrecke’ Schreckenbach, the stalwart midfielder whose long path to legendary status at Lichtenberg began with a free transfer from Dynamo. “Before the GDR took control of sport,” reads the text, “the founders of 47 relied on their own initiative, self-determination and independence”.

In other words, Lichtenberg 47 preceded the Stasi, which moved into the adjacent complex, a former Soviet military HQ, in the early 1950s.

For an earlier exhibition and public discussion at the Stasi Museum in 2019, also called Fußball im Hinterhof der Stasi, its curator, historian Christian Booß, interviewed older locals with first-hand experience of the stand-off between the Stasi and SG 47.

They seem unlikely hero material. These original supporters were no firebrand revolutionaries but of solid middle-class stock, pharmacists, university graduates and small-business owners. This was a grouping of players, officials and followers nurtured in Alt-Lichtenberg, a residential village subsumed into Berlin as recently as 1920.

Surviving the traumas of the previous decade, in 1947 these solid pillars of the community came together to form a private sports club, soon to be named SG Lichtenberg, whose status outside of the state mechanism was preserved for a further 22 years.

When Erich Mielke, master builder of the Berlin Wall, vented his wrath at Lichtenberg’s little victory in 1967, he did so as a rabid Communist who had blithely murdered for his beliefs in 1931. Exiled for over a decade in Stalin’s Moscow, he had studied the methods of the Cheka, the later KGB, before being flown into the apocalyptic mayhem of Soviet-occupied Berlin in the days leading up to the Nazi surrender of 1945.

Fast forward two decades. With record numbers of escapees being shot on his orders for attempting to cross the Berlin Wall, you would think that Mielke might have more important things to scream about than a solitary goal struck on a cold December day in a seemingly meaningless football match.

But there was plenty at stake that afternoon. Nationwide multi-sports association Dynamo had been created along the lines of its Soviet counterpart formed by Mielke’s role model, Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the future KGB.

Berliner FC Dynamo, aka BFC Dynamo or Dynamo Berlin, became a designated football club in 1966, the year before the fateful game in question. They were to represent the Interior Ministry and, similarly, the Secret Police, by dint of honorary president, Erich Mielke.

Dynamo were also to act as the flagship for the capital of the GDR, as a counterweight to Hertha in West Berlin, who had a significant if clandestine following in the East. Until 1963, Hertha played at die Plumpe, aka Stadion am Gesundbrunnen, right by the Berlin Wall, in the working-class district of Wedding. This was where Mielke grew up, in dire poverty, a lonely malcontent orphan easily swayed by the many Marxist revolutionaries around him.

There was more to his reaction, then, than a man shouting at shopkeepers. In their first season, Dynamo, the pride of East Berlin, had been immediately relegated from the GDR’s top-flight Oberliga. In 1967, the Weineroten faced SG Lichtenberg in the regionalised second-tier DDR Liga, whose average attendance that season fell below 3,000. Some games were played in front of a few hundred. This wasn’t the stuff of future European contenders and promotion was paramount.

There was another aspect to Mielke’s ire. The Hans-Zoschke-Stadion was named after a Lichtenberg local who had played for SC Empor, forerunner of SG 47, a talented footballer who had turned his attention to actively resisting the Nazis. While Mielke was 2,000km away in Moscow, Zoschke was on these same streets marching in protest and handing out anti-Fascist leaflets. In terms of brave opposition, he was everything that Mielke wasn’t.

Arrested in 1933, he was tortured and later executed in 1944. Zoschke’s legacy was cemented when the stadium was named in his honour in 1951 – around the same time that Saxon accents started to be heard in the streets around it, the children of the employees drafted in from out of town to work at the sprawling Stasi HQ.

These were not only agents of fear and mistrust, they were arrivistes, interlopers – and this was Lichtenberg. It is said that Zoschke’s widow appealed to soon-to-be GDR leader Erich Honecker to dissuade Mielke from tearing down the stadium.

Though there wasn’t out-and-out confrontation, the win of December 1967 was duly celebrated, and locals exuded a sense of smug self-confidence that may not have been perceived in neighbouring Friedrichshain, say.

It couldn’t last and it didn’t. By 1969, SG Lichtenberg had been squeezed out financially to such an extent that the club needed to turn to a sponsor, BSG Elpro, involved in plant construction and electrical installation.

The creation of BSG EAB Lichtenberg 47 ended 22 years of this community team operating as a private sports club. They would spend the following 20 years treading water in the second and third tiers of the GDR league.

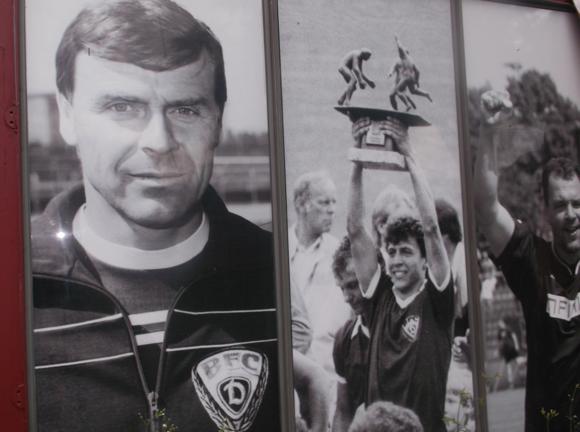

Dynamo Berlin’s domestic domination allowed the Weinroten to face the finest European sides of the 1970s and 1980s, Liverpool, Brian Clough’s Forest and St-Étienne included. The match pennants can still be seen in the Vereinsheim club bar at Dynamo’s regular home ground, the Sportforum Hohenschönhausen, a few stops on the M13 tram from the Hans-Zoschke-Stadion.

Erich Mielke attended his last Dynamo game in September 1989, before the GDR crumbled along with his Wall. At the Stasi HQ in Lichtenberg, in panic measures to remove all documentation, paper shredders overheated and konked out, forcing agents to buy more from West Berlin or resort to scissors.

In what would be his last speech to the GDR Parliament, Mielke was openly mocked by his own peers for claiming he loved all humanity. He spent the next decade either in prison or on trial, including for the 1931 murder. He died in 2000.

Without state support, all clubs from the former GDR struggled post-Unification. Recalibrated as SV Lichtenberg 47, the club from Ruschestraße maintained a presence in the lower reaches of the all-German league pyramid.

Until relegation in 2023, four seasons in the fourth-tier Regionalliga Nordost allowed the Reds to share divisional status with Dynamo. The two often meet in the Berlin Cup, such as in the final in 2013, the first of two runners-up medals for SV 47.

As for the stadium, nearly 60 years after threats of its demolition, the Hans-Zoschke-Stadion is one of Berlin’s great groundhopping experiences. With a capacity of just under 10,000, the ground keeps fans close to the action, with no running track or VIP areas. Concrete terraces line the pitch, where the weathered surroundings create an electric atmosphere. Each pass, each tackle, each goal feels raw and real.

Wooden shacks serve bratwurst and beer, while fans eagerly queue for vintage badges, scarves and pennants. This writer once witnessed Lichtenberg 47 demolish FSV Optik Rathenow 7-0. Each goal was manually updated on the scoreboard, a playful (and slightly cruel) act of mischief as the volunteer fumbled to find the number 7.

The Hans-Zoschke-Stadion is a shrine to community, resilience and grassroots football – a lesson in living history as fascinating as the Stasi Museum it still faces.

BFC Dynamo v SV Lichtenberg 47, Sportforum Rasenplatz NR2, Saturday, January 18, 1pm.