Schön, Müller, Beckenbauer, German heroes all – but Alan Deamer chances upon an unsung legend

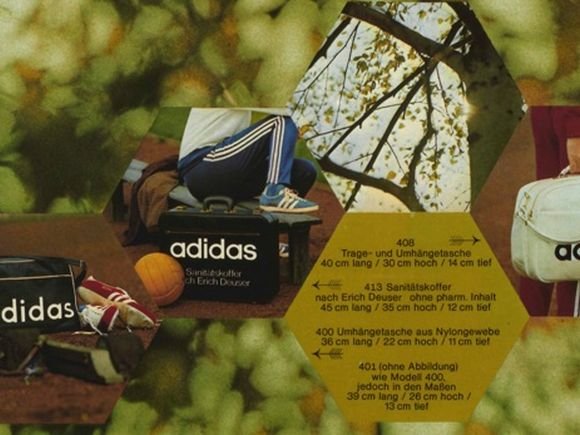

Shining out like a shrine amid the musty threads in a thrift store in Dijon, a striking black adidas bag bore the signature white trefoil stamped with Sanitätskoffer nach Erich Deuser (‘Erich Deuser Medical Kit’).

Though sadly not for sale, this sacrosanct piece of German football history inspired me to delve into the life and work of one of the game’s unsung pioneers: Erich Deuser, whose groundbreaking methods shaped modern football therapy.

Born in Düsseldorf in 1910, Deuser started as a pharmacist but quickly pivoted to physiotherapy, passing his state exam as a masseur at just 21. His own battles with illness – including a year-long paralysis from diphtheria while serving as a soldier – forged his relentless curiosity for rehabilitation and innovative treatment methods.

He experimented with underwater massage, natural remedies and early strengthening techniques, blending science and personal experience long before modern sports therapy existed.

Deuser made his mark at Fortuna Düsseldorf, earning a reputation for precision and intuition. In 1951, he joined Sepp Herberger’s German national team, eventually serving the Nationalelf for more than 300 matches, including the victorious World Cup campaigns of 1954 and 1974.

But it was his prominent role at the 1970 World Cup – receiving the tournament’s only (and therefore first-ever) red card in his haste to tend to an injured player in the game with Peru, working on Schnellinger’s tired legs to conjure another 30 minutes of football out of them in the epic semi with Italy – that earned Deuser brief fame.

There was even a two-part documentary made about him soon afterwards, Golden Hands. In the dramatic quarter-final, Grabowski’s swift run, Löhr’s prodigious leap and Müller’s aerial twist for the winning goal came deep into extra-time as England wilted. From 0-2 down, in the murderous heat of León, the Germans were again swarming on the attack. How did they do it?

Players and coaches hailed Deuser as indispensable. One of the heroes of 1974, Bernd Hölzenbein, described him as having “miracle powers”, while Olympic silver medal-winning athlete Karl-Friedrich Haas credited him with keeping him fit for the 1956 Melbourne Games.

Even wily coach Helmut Schön joked that, in another era, Deuser would have been accused of sorcery.

While Schön and his ever-present cap were celebrated in song as der Mann mit der Mütze, der Mann mit dem Koffer, Deuser and his medical bag, mainly went unsung.

His most famous creation, the Deuser-Band – fashioned from bicycle inner tubes – let players strengthen muscles safely and effectively, a precursor to the resistance bands now standard in gyms and football training worldwide. Beyond this, Deuser’s methodical approach to stretching, massage and injury prevention extended careers and improved performance, laying the foundations for the professionalism in player care that often taken for granted today.

Deuser stayed out of the spotlight, preferring to work quietly behind the scenes, yet his influence on German football was profound. He authored six books, passing his expertise to future generations, and left a legacy measured not in trophies, but in the fitness, resilience and longevity of the players he cared for.

His contribution even stretched to the bag he carried. Collaborating with the founder of adidas, Deuser and Adi Dassler together created a holdall for medical and first-aid use, with four small interior pockets and straps to hold instruments.

The first record of such a specialised accessory came in the World Cup year of 1970, with its name displayed from 1971 onwards, and the adidas trefoil added in 1974, by no small coincidence another World Cup year. The first-aid bag stayed on the market until the mid-1980s.

Erich Deuser died in 1993 just shy of his 83rd birthday in his native Düsseldorf. On the centenary of his birth in 2010, his former club Fortuna hailed him a ‘Hero of Berne’, a reference to the miraculous World Cup victory of 1954.

Deuser’s influence is a reminder that behind every triumph is the unseen work of pioneers who made football safer, stronger and more professional. Today, his methods underpin modern football therapy, from professional academies to national teams, his innovations – like the Deuser-Band – used in gyms and physio rooms worldwide.

Yet his name remains largely unknown outside specialist circles. It doesn’t feature in the Hall of Fame at the German National Football Museum, recently augmented by Bert Trautmann and Bastian Schweinsteiger, among others.

A vintage Adidas bag in Dijon, stamped with his identity, tells the story better than any trophy cabinet could: here lies a legacy of care, science and quiet brilliance that changed the way footballers are trained, treated and protected.