A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

Borussia Dortmund are a giant, populist club in Germany’s beer-fuelled heartland, who have bounced back from the Klopp era to make the Champions League final in 2024 and come within an agonising 90 minutes of winning the title.

While the end of Jürgen Klopp’s reign as manager in 2015 makes for a convenient milestone in the club’s stellar history, in truth Dortmund, spurred on by the biggest crowd in the game, have hardly ever not been in contention this century.

Runners-up (to Bayern, natürlich) five times between 2016 and 2023, the year of the most galling of silver medals, the side from the Ruhr made the knock-out stages of the Champions League every year but two during those eight seasons.

In May 2024, with the scene set for a repeat of the all-German final of 2013, and on the same stage of Wembley, Bayern fluffed their lines late in the second leg of the semi-final, while a determined Dortmund stood their ground against PSG. A final pairing with Real echoed the epic semi of 2013, the apogee of Jürgen Klopp’s seven-year tenure.

With the highest average attendance in European football, 80,000-plus, despite Bayern’s consistent domestic dominance, Dortmund will always be there or thereabouts. Backed by the solid Südtribüne of 24,454 standing fans every other Saturday, Borussia generate the kind of revenue other clubs can only dream of.

While Borussia fell to Bayern in that Champions League final of 2013, Dortmund had at least rejoined the footballing elite after facing financial ruin a decade before. Ironically, back then it was Bayern who had lent their rivals the funds to make payroll. The Bavarians know the value of a powerful opponent.

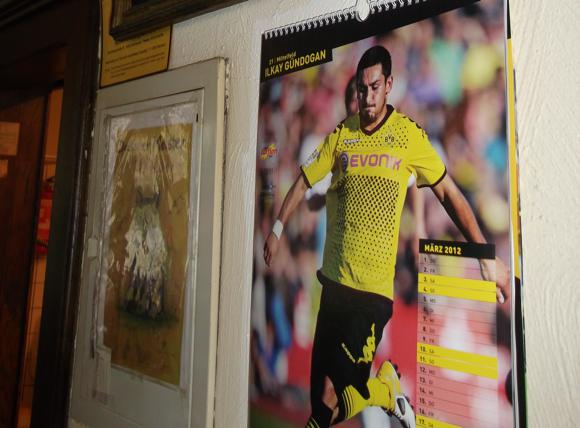

The ‘09’ on the BVB (‘Ballspiel Verein Borussia’) badge refers to the year a group of young men founded the club at the Zum Wildschütz pub, naming it after a local brewery. Borussia were based at the Weiße Wiese on Wambeler Straße, near Borsigplatz, BVB’s spiritual home north-east of town where bars are still decked out in yellow-and-black memorabilia.

Meanwhile, opened as part of the Volkspark communal sports complex in 1926, the Rote Erde was hosting mainly athletics meets south of the city centre. Relocating to the ‘Red Earth’, Borussia moved focus from the local rivalry (the Revierderby) with neighbours Schalke 04 to gain national success in the mid-1950s thanks to the Three Alfredos – in actual fact, three Alfreds, Preißler, Kelbassa and Niepieklo.

Holding a capacity 42,000, the Rote Erde was heaving on big nights, such as during the European Cup run of 1963-64 and high-profile games against Benfica, Dukla Prague and Internazionale. This basic if atmospheric ground embraced the new European era, black-and-white footage capturing the din of the klaxons and flag-waving fans.

BVB really took off in the mid-1960s. Spearheaded by Siggi Held, Reinhard ‘Stan’ Libuda and Lothar Emmerich, prominent for West Germany at two successful World Cups, Borussia won league, cup and the Cup Winners’ Cup of 1966, the first German club to lift a European trophy.

Bizarrely, though, as German football boomed, Borussia dipped. Relegation in 1972 coincided with the decision to build a much-needed new stadium alongside the tatty wooden Rote Erde, Dortmund getting the nod as a 1974 World Cup host over Cologne. The Westfalenstadion, today the Signal Iduna Park, proved a huge success.

At club level, though, Borussia still struggled. Perhaps difficult to believe now, but the club went 20 years with next to no European football, a solitary defeat at the hands of Glasgow Rangers representing BVB’s only appearance between 1966 and 1987.

The arrival of coach Ottmar Hitzfeld in 1991 changed all that. Welcoming prolific Swiss striker Stéphane Chapuisat, Hitzfeld took his new charges to within 90 minutes of a Bundesliga title in 1992, then to a European final a year later. Though well beaten by Juventus in the UEFA Cup final, BVB were once more a team to be feared. Two years later, facing Juventus in the semi-final of the same tournament, Dortmund led the Italians 2-1 in Turin before a late goal from Jürgen Kohler rebalanced the tie.

With a team of returnees from Serie A – Kohler himself, Matthias Sammer and Andreas Möller – Dortmund won back-to-back Bundesliga titles then surprisingly gained revenge over Juventus in the Champions League final of 1997. A wonder chip from Lars Ricken, only seconds after coming on as substitute, brought the trophy to Dortmund.

A long-term injury to Sammer and managerial changes saw Dortmund give way to Bayern. Sammer returned as coach to take the club to another league title in 2002.

Financial mismanagement led to near bankruptcy before Borussia signed a long-term stadium sponsorship agreement with insurers Signal Iduna, on the eve of the 2006 World Cup.

On the pitch, the turning point came with the arrival of young coach Jürgen Klopp in 2008. Klopp created a side based around central defender, Mats Hummels, midfielders Kevin Großkreutz and Mario Götze, and forwards Robert Lewandowski and Shinji Kagawa, that would take the Bundesliga title in 2011, and the double with then record league points in 2012.

With the sale of Kagawa to Manchester United, Borussia started 2012-13 slowly. Europe was a different matter. In-form Marco Reus and Felipe Santana scored well into overtime to beat Málaga in an extraordinary Champions League quarter-final. This led to the history-shifting 4-1 demolition of Real Madrid in the semi, all four goals coming from Lewandowski. The Pole had chances to score in the final at Wembley but Bayern proved too strong.

Klopp’s farewell season was always going to be an emotional rollercoaster, so BVB skirted relegation, beat local rivals Schalke 3-0, entered the Europa League through the back door and lost the German Cup final to Wolfsburg after taking an early lead.

Klopp’s replacement Thomas Tuchel, who had also worked wonders at Mainz, enjoyed a cracking start to the 2015-16 campaign, but then proved unlucky in all three competitions. In Europe, Tuchel ran up against Klopp, whose Liverpool side just pipped Dortmund in a heartstopping photo finish at Anfield. In the German Cup final, penalties saw the trophy go to Bayern, also too strong in the league. In any other season, a meagre four defeats would have swung the title in the direction of Westphalia.

On the plus side, Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang was surpassing every striker in the Bundesliga bar Robert Lewandowski, now at Bayern. This form continued into 2016-17, when the Gabonese international hit 40 goals in all competitions. Though coinciding with the spectacular rise of young American Christian Pulisic, it was never quite enough. Fate conspired to work against the Ruhr side, when explosions near the team bus before a Champions League quarter-final with Monaco hindered morale and concentration.

This unfortunate event exposed the fracture between the club’s long-term CEO (and lifelong Dortmund fan) Hans-Joachim Watzke, who had engineered Borussia’s recovery in 2005, and coach Thomas Tuchel, who wanted the tie to be postponed. The former Mainz man’s days were numbered from then on.

An Aubameyang penalty at least brought the German Cup to Dortmund after three successive final defeats. The occasion proved to be Tuchel’s farewell as coach. Peter Bosz repeated the bright start of his predecessor only to suffer vital defeats in Europe and, inevitably, to Bayern.

Similarly, Lucien Favre set off on a 15-game unbeaten run in the league in 2018-19, the breakthrough season for another teenage prodigy, Londoner Jadon Sancho, surpassing various scoring records for his age and making the Bundesliga XI for the season. The club’s top scorer the following campaign, Sancho was joined by a crop of significant signings, most notably €20 million goal machine Erling Haaland from Salzburg and the former Dortmund centre-back returning from Bayern, Mats Hummels, for €30 million.

Two Haaland goals put Dortmund in the driving seat against PSG in the first knock-out round of the Champions League, but between the two legs, the pandemic had broken out, lockdown was in place and the Parisians prevailed at an empty Parc des Princes. From now on, Dortmund’s legendary crowd numbers could no longer generate revenue.

The club did stump up €25 million for Jude Bellingham, the promising teenager inspired by Sancho’s example and setting the Bundesliga ablaze almost immediately. With Haaland eventually hitting 41 goals for the season, Dortmund should have been cruising to the title in 2020-21 – instead, they sacked Favre halfway through and brought in their former scout from the Klopp era, Edin Terzić.

An unstoppable Haaland scoring twice in each leg allowed Dortmund to see off Sevilla in the Champions League Round of 16 in early 2021, before a late goal by Marco Reus at Manchester City put Guardiola’s side in jeopardy for the return game in Germany. Despite an early strike from Newcomer of the Year Bellingham, Borussia fell to the stronger side.

Unable to resist a €85 million offer for Sancho from Manchester United, BVB still pushed Bayern hard for the title, Haaland and Bellingham sharing scoring duties. Following the Norwegian’s departure for €60 million, the former Birmingham City man thrived in 2022-23, earning himself the Bundesliga Player of the Season award but not the league title that had been in Dortmund’s hands going into the last game of the campaign.

Only needing a win at home to mid-table Mainz to end the Bavarians’ Bundesliga monopoly, Borussia froze. Trailing to 0-1 to the visitors with Bayern leading by the same scoreline at Köln, Dortmund were awarded a penalty on 20 minutes. Up stepped Sébastien Haller, who had undergone months of chemotherapy for testicular cancer immediately after his arrival from Ajax the previous July.

A redemptive equaliser would have changed the game. Instead, Haller’s weak shot was saved. Minutes later, an error at the other end from Dortmund keeper Gregor Kobel clicked the deficit up to 0-2. With Bellingham on the bench injured, the game ran away from the hosts, a deafening silence from 80,000 expectant spectators greeting the final whistle. Bayern had won the title. Again.

The English international’s last action as a Dortmund player was to push away the camera from his face and make a swift, tearful exit for the tunnel. Within weeks, for €100 million-plus, he was a Real Madrid player.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

Built for the 1974 World Cup, the Signal Iduna Park is the perfect football ground. It’s also, in Germany at least, the largest. Every other weekend, it accommodates the highest average crowd in Europe, around 80,000, nearly a third forming part of the famed Yellow Wall, the standing Südtribune.

When it comes to international fixtures – and Dortmund’s ground has hosted two World Cup semi-finals – the Südtribüne fills with temporary seating that takes an inordinate number of man hours to remove afterwards. These details and many more colour the commentary of the excellent stadium tour here, 90 minutes of info-packed entertainment, with video films at various points.

The former Westfalenstadion still overshadows the modest ground it usurped, the Rote Erde. A new stadium had long been proposed. In 1971, Cologne turned down the chance of being a venue for 1974 World Cup, so the opportunity, and the funds, passed to Dortmund. First staging the Revierderby with Schalke 04 in April 1974, this 54,000-capacity football-specific ground hosted four games for the finals, including the de facto semi between Holland and Brazil.

As Borussia gradually rejoined the European elite, so the Westfalenstadion kept increasing capacity, first 68,600, then 83,000. For the 2006 World Cup, architects Engels and Partners unveiled €35ml worth of improvements, including five video screens. Capacity fell back to an all-seated 65,000 – not that many would have been calmly sitting down during Germany’s epic semi-final with Italy.

Thereafter, the stadium reverted back to its sponsored name of the Signal Iduna Park and capacity has slowly been creeping up, for domestic fixtures at least, ever since. Currently it holds 81,645 in four main stands: the Nord- and Südtribune behind each goal, the West- and Osttribune along the sidelines.

Away fans are allocated the north-east corner of the Nordtribune, and the nearest sectors to it behind the goal. These include 08, 70, 75, 55-59 and standing sections 60-61. Note that unsold tickets in the away sector are made available to neutrals (see Getting in).

For Euro 2024, capacity has been capped at 61,524, with another semi-final likely to raise the roof.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

The stadium is south of town, a 25min walk from the centre down Hohe Straße. Signal Iduna Park has its own train station, one stop/five minutes from Dortmund’s main Hauptbahnhof, quick, easy and cheap, €2.70/single. Buying a ticket from the machine that day means you don’t have to stamp it. Usually four trains run an hour, with extra ones on match days, when your match ticket is valid.

Trains leave from platform 4 at Dortmund Hbf, tucked away from the main platforms. They arrive just behind the swimming pool, part of the Rote Erde sports complex. Once you cross the station walkway, depending on where your seats are located, you cut through the Rote Erde ground for the Nord- and Osttribüne, or head left for the West- and Südtribüne. Attractions such as the Kronen Biergarten, Strobels bar, Borusseum museum and Fanwelt BVB megastore, are all behind the Nordtribüne.

Alternatively, the Stadion stop on the north side, close to the Kronen Biergarten and Strobels, operates on match days only, on the U45 light-rail line, direct from Dortmund Hbf, 12min journey time. This brings you slightly closer to the stadium. On non-match days, though, the U45 only runs as far as Westfalenhallen, a 10min walk to the ground through Rosenterrassen.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Despite a stadium capacity of 81,360, ticket availability is at a premium. Tickets go on sale four to six weeks before each home game and purchases are limited to four per person, two for ‘Top-Spielen’, including Bayern and Schalke 04.

If you’re keen on seeing any game at Dortmund, bear in mind that German guidelines mean that the visiting club is allocated 10% of the overall gate, ie 8,000 – and unsold tickets are returned for sale to neutrals. European and cup games are also easier to access – one week before the home Champions League tie with Tottenham in November 2017, there were still a few tickets available via the Dortmund website (see below).

The club stresses that the first means of buying tickets is via its hotline, +49 1805 309000. As this service is charged at €0.14/min from a German landline, €0.42/min from a German mobile, the costs of hanging on when dialling from abroad – and you will be hanging on, there have been 300,000 requests in one day before Bayern and Schalke games – could be astronomical.

The alternatives are to purchase in person from BVB FanWelt (Mon-Fri 10am-6.30pm, run-up to match day from 8.30am, match days 10am-kick off) on Strobelallee – which would probably require you to make two trips to Dortmund – or online through German-only Eventim.

For all requests for ticket information, you can email the club via an English-language contact form, fax (remember those?) on +49 231 9020 3109 or the ever-busy and expensive hotline, +49 1805 309000.

The kiosks on Strobelallee open 4.5hr before kick-off but it is extremely rare (but not unheard of) for tickets to be available on match days.

There are six main categories of ticket, excluding the sold-out standing Stehplätze behind the goal. Affordable blue category 4 (€45) is close to the action in the corners, with yellow 5 and green 6 behind (€31-€38). The best seats are in the Osttribune (€51-€55). ‘Top-Spielen’ (currently games with Bayern, Schalke 04, and any major European opposition past the group stages) are 20% dearer. As a rule of thumb, the remaining tickets for Tottenham’s visit of 2017 were priced around €35-€40.

Borussia Dortmund also run a scheme with for weekend match packages with nearby hotels, comprising upscale accommodation, match tickets and various discounts and souvenirs thrown in.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

The club has several outlets in the city and surrounding towns, including Essen and Oberhausen. The main store is the gleaming two-storey BVB FanWelt (Mon-Fri 10am-6.30pm, run-up to match day from 8.30am, match days 10am-1hr after final whistle) on Strobelallee at the north-west corner of the stadium.

In the city centre, you’ll find the FanShop Krone (Mon-Fri 10am-7pm, Sat 10am-6pm, match days 10am-30min before kick-off) on the main square, Markt, and late-opening FanShop Thier Galerie (Mon-Thur 10am-8pm, Fri-Sat 10am-10pm) in the shopping centre of the same name on Westenhellweg. Next door to the Markt store, Karstadt Sports (Mon-Sat 9.30am-8pm) also sells BVB gear.

At FanWelt, you’ll find two floors of black-and-yellow merchandise, as well as a three-a-side football game and a mock of a section of terracing backdropped by a huge mural of the Yellow Wall. More unusual purchases include scale models of the stadium, CDs of Borussia songs (Nur der BVB!), beer mugs with an image of the Südtribüne emblazoned over them, and welcome mats with the word ‘Heimat’ (‘Home’) on them and the outline of the stadium. It has also has a café so you can sit and browse your purchases.

Museum & Tours

Explore the club inside and out

German-language BVB-Tours run frequently from 11am or noon, every day of the week apart from match days. Usually there’s an English-language tour scheduled at least once over a weekend, often twice. Booking is in German. The 90-minute version is €12 (discounts €8), the two-hour German-only BVB-Plus including the Rote Erde, €15/€10.

Both are excellent and the witty, entertaining tour guide will defer to English when requested. This means that you get to find out why Borussia players have 12 steps to take from coach arrival to dressing room and the opposition 13, which famous international player needed lagoons of Dortmund lager before he could produce the required result in the post-match urine test, and other wonderful trivia. What makes this stadium visit different is that TV clips pop up around the tour, so you get to meet kit man Frank Gräfen in video form as you sit in Christian Pulisic’s old seat in the BVB changing room. You also get to stand on the Südtribüne, a rare privilege.

Tours start by the cash tills of FanWelt or, on Sundays and holidays, at the Borusseum museum (Mon-Fri 10am-6pm, Sat-Sun 9.30am-6pm, match days until kick-off; museum only €6/under-18s €4, under 6s free). This detailed and visually entertaining history, in German only, starts with a mock of the pre-war bar Zum Wildschütz where Borussia were founded, moving onto original TV re-runs of vintage triumphs (note Libuda’s sublime winning lob of 1966) and many things to press, open, watch and listen to.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

Fans walking towards the stadium down Hohe Straße, its pavement lined with stars commemorating BVB heroes, first stop at the corner of Mittestraße for sausage and chips amid Borussia paraphernalia at the Gourmet Stäbchen Imbiß.

Further down Hohe Straße, Semmler (No.117) is a traditional restaurant offering match-day specials while the ever-trendy Balke (No.127) has gone full cocktail, now opening from 6pm and serving its own gin. The restaurant at the Hotel Gildenhof (No.139) also does match-day specials and puts out tables on the pavement.

By Westfalenhallen U-Bahn, Rosenterrassen is a pleasant outdoor spot overlooking the namesake rose garden, with the stadium in sight.

Alongside the stadium, Strobels is the BVB pre- and post-match hangout. This party-minded bar/restaurant with adjoining terrace is perfectly set up for the occasion, a special grill menu in operation for home or away games, shown on 12 big screens and another the size of a house. Brinkhoff’s No.1 is the go-to choice for beer on draught, complemented by Schlösser Alt and pricier Hövels Original.

Next to it, the traditional Biergarten overlooks the Rote Erde pitch, serving beer from one hut and grilled sausages from another. It opens from 4pm Tue-Sat unless there’s a game on, and from 1pm Sundays.

In the ground, an army of vendors and multitude of kiosks dispense real beer and sausages. Payments are either contactless or through a Stadiondeckel chip card, no deposit required, €5 minimum charge-up. Stands for Stadiondeckel distribution also deal with refunds from 60 minutes into the game.