A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

Beerschot’s promotion back to Belgium’s top-flight Pro League in 2024 coincided with the club’s 125th anniversary. The path there has been far from smooth – bankruptcies and new identities have almost equalled the seven Belgian titles won by the club between the wars.

Its current iteration dates back to 2013, which is exactly a century after a New Beerschot Athletic Club had to be created from the original BAC established by the Grisar family in 1899.

Buying a racetrack and the surrounding grounds in the well-to-do district of het Kiel, south Antwerp, industrialist Ernest Grisar died before a football department could be set up, leaving his sport-mad teenage son Alfred to take on the responsibility in 1900.

The name came from a nearby park, Beerschothof. The colour purple represents mourning, in honour of Beerschot’s recently deceased founder.

Weeks after their formation, Beerschot AC welcomed disaffected players from across the city. Nicknamed The Great Old, Royal Antwerp had already been in operation for 20 years but had not been able to break the monopoly held by teams from Brussels and Liège in the initial days of the Belgian championship.

Headed by wealthy brokers and merchants, Beerschot seemed the more ambitious option, forming a limited company among its moneyed shareholders and quickly overshadowing their city rivals.

The pitch in het Kiel also hosted early internationals between Belgium and Holland, from 1905 onwards.

But until the Great War that devastated so much of Belgium, the title would only leave Brussels once, to go to Bruges in 1911. The young Grisar soon found that running so many sports departments was a costly undertaking.

It would also prove to be a useful one. Despite having to rename and reform their club in 1913, Beerschot’s various chairmen could collaborate on a much bigger project once Belgium had made its bid in 1912 to host the 1920 Olympic Games.

Sympathy for the dreadful hardships suffered during World War I, the support of France and the enforced withdrawal of Budapest paved the way for the Games to come to Belgium, as Alfred Grisar and his fellow administrators at Beerschot directed the spotlight onto Antwerp, which got the nod days after the Armistice was signed in November 1918.

The city had less than 18 months to prepare, which included building an Olympic Stadium on the Kiel site. On the executive committee for the event, Grisar oversaw operations, from the laying of the foundation stone in July 1919 to the opening ceremony 13 months later.

The first time it was to feature the raising of the Olympic flag, the communal pledge to the Olympic oath and the mass release of doves, the Games were nothing if not symbolic. Much of Europe still lay in ruins.

Built on the site of Beerschot’s original ground, the grandiose Olympisch Stadion proved a worthy if incomplete setting for the athletics, equestrian and rugby competitions, as well as the main football matches.

The Games also coincided with the arrival of a young generation of Beerschot players, including half-back Henri Lamoe, whose controversial second goal for his country in the final against the favourites, newly independent Czechoslovakia, caused the visitors to walk off the pitch in protest.

Before 35,000 at the Olympisch Stadion, Belgium were granted the gold medal, the only occasion so far that a major global football final has had to be abandoned. At domestic level, this success gave Beerschot the fillip they needed to overcome the previously dominant sides from Brussels.

Gold medallist Lamoe was soon joined by the greatest Belgian player of the day, Raymond Braine. Born in nearby Berchem, this prolific striker was only 16 when he first donned the purple jersey in 1923, following the path of his elder brother, Pierre.

The pair would go on to win exactly 100 caps between them, a significant haul in these days of mainly friendly fixtures. When Belgium did enter the first World Cup of 1930, Pierre was their captain.

As for Raymond, he was the star of the side that won three league titles on the bounce from 1924-26, each under Scots coach Johnny Dick. A former captain of Woolwich Arsenal, Dick had learned much of his tactical nous in Prague, where he had followed his compatriot, Johnny Madden, in the run-up to World War I.

While Madden coached Slavia for 25 years – his gravestone in Prague bears the club’s red star – Dick took over their rivals, Sparta. In 1923, he was persuaded to come to Antwerp to oversee Beerschot’s golden era.

In 1930, having returned to Sparta, he lured Raymond Braine to the club, the first Belgian to be transferred abroad. Top league scorer at home in 1928 and 1929, he repeated the feat in the Czech league, winning two titles, but returned to Beerschot in 1936 after turning down the option of Czech nationality.

Beerschot duly won two more titles and provided a third of Belgium’s squad at the 1938 World Cup, Raymond Braine included.

By now, the club were Royal Beerschot AC, having earned the regal title after 25 years of operation. Consistency was the club’s watchword, an unbroken run in the top division culminating in a solitary season in the second-flight Tweede Klasse in 1981-82.

Braine had hung up his boots in the 1940s, shortly before a teenager by the name of Rik Coppens burst onto the scene. This Antwerp-born trickster was the star of the immediate post-war period, dancing past defenders and pushing Beerschot back into contention.

Coveted by Europe’s top clubs on the eve of the European era, Coppens would not follow Raymond Braine’s example as Beerschot refused to let him go. Eventually, he had one argument too many with the board and headed to Charleroi in 1961.

While the 47-time Belgian international never won any silverware in a purple shirt, he earned the acclaim of young Pelé for his wonder goal against a rampant Santos at an exhibition game at the Olympisch Stadion in 1960.

Coppens would return to Beerschot, twice, as coach in the 1970s and 1980s. The first spell dovetailed with the blossoming of another young talent at Beerschot, this one Spanish-born. Juan Lozano was one of many sons of economic migrants in post-war Belgium, growing up near the Olympisch Stadion and joining the youth ranks shortly after the club turned professional in the later 1960s.

With the change of status came a change of name – Koninklijke Beerschot Voetbal en Atletiek Vereniging or K Beerschot VAV – and the wherewithal to hire top foreign players, such as 1966 World Cup star Lothar Emmerich from Borussia Dortmund. Leading scorer in the Belgian league in 1969-70, the West German helped push Beerschot into Europe and led the line with the Antwerp side won their first Belgian Cup in 1971, a 2-1 win over Sint-Truiden.

The Antwerp side repeated the feat at the end of the decade, this time with World Cup stars, Polish keeper Jan Tomaszewski and Haitian striker Emmanuel Sanon, in the line-up – along with Juan Lozano.

Though he would never play for either Spain or Belgium, Lozano was a star turn in what was a golden era for Belgian football, top clubs regularly making European finals. Though Beerschot never shone on the international stage – a 7-0 thrashing of Anorthorsis Famagusta was the highlight of their four campaigns during a decade or so – they were usually there or thereabouts in the league until Lozano headed across the Atlantic to join Johan Cruyff at the Washington Diplomats in 1980.

He would later win honours for Anderlecht and Real Madrid, while Beerschot plunged into ignominy and misfortune. The relegation of 1981 was not only a first since 1907, it was not even decided by league placing, rather the suspicion of bribery to keep the club up.

Worse was to follow in 1991, when Beerschot were demoted to the third flight for financial impropriety, overcoming the likes of KVV Overpelt Fabriek and KFC Poederlee to scramble up to the Tweede Klasse.

But promotion to Eerste Klasse never came, in stark contrast to city rivals Antwerp, who strode out at Wembley for a European final in 1993. Two name changes later, and Beerschot were no more, the original club folding in 1999, their gilded matricule number of 13 withdraw. Standing at the top of Belgium’s historic index, of course, were Antwerp, the No.1 still proudly displayed on the club badge.

Beerschot’s last fixture was an amateur team filled with youth players unable to beat little-known Rita Berlaar at the once stately Olympisch Stadion, ironically undergoing a much-needed modernization at the time.

Fourteen points from safety, with only four wins all season, rather than fall any further, Beerschot threw in the towel. A few weeks later, they merged with Germinal Ekeren, whose ground in Antwerp’s northern suburbs did not match up to their European ambitions. Belgian Cup winners in 1997, during the 1990s, Ekeren had faced the likes of Celtic, VfB Stuttgart and Red Star Belgrade and had not been disgraced – but the key investors in this new amalgamation were more interested in what was in the pipeline.

Ajax bankrolled this dream ticket – Beerschot had the stadium and the fan base, Ekeren the potential stars – in order to nurture and then nab the likes of Thomas Vermaelen, Jan Vertonghen and Toby Alderweireld, all to be mainstays in the Premier League after stints in Amsterdam.

As for Germinal Beerschot Antwerp, apart from a solitary Belgian Cup win in 2005, the club never finished higher than fifth in the league. Once the young talent stopped coming through, Ajax stopped sending the cheques and Beerschot slipped down the table.

In stepped Leuven entrepreneur Patrick Vanoppen, who bought out incumbent chairman Jos Verhaegen and set about restoring Beerschot’s previous identity under the name of Koninklijke Beerschot Antwerpen Club and with the figure of a bear on the club’s logo.

Vanoppen even reintroduced the iconic number 13, which previously identified Beerschot according to the Belgian FA’s register, in the most unusual of ways: the pitch at the Olympisch Stadion would now be 13×8 metres long and 13×5 metres wide. Verhaegen and the rest of the board simply went across town to invest their money in Royal Antwerp.

Vanoppen’s reconfigured Beerschot lasted all of two seasons, both mediocre, the second ending in relegation – only the property tycoon was not in it for the long haul. This iteration of Beerschot duly folded in 2013, and this time it was the supporters who resurrected the venerable club, hooking up with KFCO Wilrijk. The choice of partner was no coincidence, for it was Beerschot fans who had been involved in founding the club in 1921, representing the district alongside Kiel.

Apart from two seasons in the second tier just before the war, Wilrijk spent decades in the lower reaches of Belgium’s football pyramid. Given their credible matricule number of 155 and local heritage, the merger made perfect sense, to supporters as well as the City of Antwerp, only too glad to have regular football played at the recently renovated Olympisch Stadion.

From 2013 onwards, KFCO Beerschot Wilrijk achieved four straight promotions, climbing from the fifth tier to the second, with a season effectively on hold in between for the league restructuring of 2016.

Despite the disappointment of missing out on reaching the top tier in 2018, a last-minute penalty at Cercle Bruges deciding the play-off, the club went ahead with reclaiming their old matricule number of 13 for €40,000, and once more became Koninklijke Beerschot Voetbalclub Antwerpen: Beerschot VA for short.

Backing move wasn’t a group of purple-shirted enthusiasts but a Saudi prince, Abdullah bin Mossad Al Saud. The former head of the Saudi Olympic Committee was building up a portfolio of football clubs to add to his long-term support of Asia’s most decorated team, Al Hilal, and concurrent ownership of Sheffield United.

A few months after Prince Abdullah increased his shareholding in Beerschot to 75%, the team gained promotion to Belgium’s top division, though there were no fans to watch Hernán Losada’s men win the play-off after two consecutive failures at this final hurdle.

Deep into the pandemic restrictions in August 2020, the Antwerp side thumped Leuven 4-1 in Heverlee, the echoing King Power an Den Dreef Stadion a far cry from the near capacity crowd gathered at the Olympisch Stadion for the first leg the previous March.

At Losada’s side was little-known Will Still, who had got into coaching as a teenager, gaining experience on training courses and by acting as a video analyst for Sint-Truiden. With little playing experience, Still landed the coaching job at Lierse.

Only 24 and without his full coaching licence, the Brussels-born strategist worked near miracles for the cash-strapped Geel-Zwart, before the club collapsed in 2018. Taken on as a coaching assistant by Beerschot, Still was given full control halfway through the club’s comeback season in the top flight after Losada left for America.

Leaving the club in a better position than after his mentor’s departure, halfway up the table and only a point from a European play-off, Still was rewarded with the sack. While the young Englishman went on to cause a sensation at Reims, setting Ligue 1 records for unbeaten runs, Beerschot placed their trust in Peter Maes and were rewarded with relegation in 2022.

Topping the extended second-tier Challenger Pro League two seasons later under former Liverpool star Dirk Kuyt, Beerschot got off to a terrible start in the Belgian Pro League, eight straight defeats culminating in a 5-0 defeat in the derby with Royal Antwerp. But Kuyt’s men showed spirit in their 2-1 defeat of Anderlecht, the record Belgian champions later drawn to play Beerschot in the quarter-final of the Belgian Cup at the Olympisch Stadion.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

Olympic stadiums – in Berlin, Rome or Athens, say –usually provide the spectator with a sense of occasion. Not so the Olympisch Stadion in Antwerp, partly because these Games took place some 125 years ago, partly because they were arranged at the last minute, right after Armistice Day, 1918, and partly because the tenants, Beerschot, have all but blipped out of existence on far too many occasions this century.

The down-at-heel surroundings, in what was a well-to-do district a century ago, hardly help.

The Olympisch Stadion lost the faded grandeur of its 1920 construction in a 2000 rebuild. All that remains is a monument on the south-east side of the stadium, erected in memory of Beerschot members who lost their lives during World War I – the list of names, however, is of club officials and sportsmen killed by a V-2 bomb attack on the Rex cinema in December 1944.

Many of those remembered were from the upper echelons of Antwerp society – the bankers, merchants and traders who ran Beerschot also helped bring the Games here to heroic, war-devastated Belgium. The stadium, converted from Beerschot’s pre-1920 het Kiel ground of one wooden stand and raised terracing, reflected this sense of dignity and prestige, a sleek colonnade forming the oval shape of the arena, bookended by a monumental triumphal arch.

This was the setting for the month-long event, several Belgian internationals – including a ding-dong 5-3 defeat to England in 1926 – and Beerschot’s seven title-winning seasons up to 1939.

Either side of two roofed stands were standing places for 20,000 for an overall capacity of 30,000. In the 1970s, the terraces were covered, then demolished for the major renovation of 2000. This made the Olympisch Stadion a functional facility of just under 13,000 capacity, all seated, the removal of the running track also altering its shape from oval to rectangular.

In more recent times, discussion has not centred around improving the stadium but moving from it – specifically, to an area known as Petroleum-Zuid, around the Blue Gate business park alongside the Scheldt.

Although just over a mile north-west of the site where Alfred Grisar’s Beerschot first set up a pitch in 1900, any migration would be a wrench, not unlike West Ham upping sticks from the East End.

As the City of Antwerp owns the stadium, Beerschot a leaseholder, a new stadium might secure the club’s future – for as long as Saudi prince, Abdullah bin Mossad Al Saud keeps pumping money in to keep the operation afloat.

While Beerschot are in the top-flight Pro League, average gates hover around 6,000, about half stadium capacity. For lesser opposition, only three stands are open, Tribunes 1 and 4 either side of the long sideline, and Tribune 4 behind the goal, with one section given over to visiting supporters.

For the Antwerp derby – for which a full house can be expected – and games with Anderlecht, Gent and Club Bruges, Tribune 3 is also open, section D sectioned off and allocated to ‘Bezoekers’.

Wherever you are, you’ll be up close to the action – something that could not have been said about the original Olympic Stadium as envisioned by Beerschot’s distinguished administrators more than a century ago.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

Tram 2 runs from Astrid Metro outside Centraal station and takes 20mins to reach the nearest stop of Antwerpen Schijfwerper 12 stops away. (Note that Olympiade refers to the junction where VIIde Olympiadelaan starts.) Trams run every 10mins Mon-Sat daytimes, 15mins Sun and 20mins eve.

From Schijfwerper, it’s a 5min walk up Atletenstraat.

If you’re coming from Groenplaats in the city centre, then take tram 4 to Grens Kiel, about the same journey time and frequency. From there, it’s a 10-15min walk down Julius de Geyterstraat.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Tickets are distributed online (Flemish-only, registration required) and in person from the Ticket Corner near the war memorial. The usual opening hours in the run-up to match day are Wed & Fri 5pm-8pm, then from 2.5hrs before kick-off.

Note that the derby game with Antwerp is usually a sell-out, otherwise availability isn’t a problem.

Admission is around €20, €22-€25 for the better seats in sector J/Tribune 3 and sectors B/C in Tribune 1.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

The Beerschot Fanstore operates on Wednesdays and Fridays in advance of a home game, opening hours usually either 10am-2pm or 2pm-6pm. During the game itself, only those with match tickets can access the shop.

The current iteration of the home shirt is seriously purple, the reintroduced bear logo not only prominent on the club badge but also superimposed around the torso. A sandy yellow has been preferred for the change strip, also with a smart round collar. Bottle green with darker tiger stripes is the colour du choix for the third kit.

The bear also features on T-shirts proclaiming, in Antwerp dialect, ‘We Geun Nor Iejeste’, suggesting the club is only heading in one direction. Other merchandise carry the club’s iconic number of XIII, a reference to the year it was refounded over a decade ago.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

Near the number 2 tram stop on VIIde Olympiadelaan, the cosy Cafe Athletiek revels in its location and tradition, original posters from the 1920 Games sharing decorative space with Beerschot team line-ups while regulars tuck into warming Belgian fare.

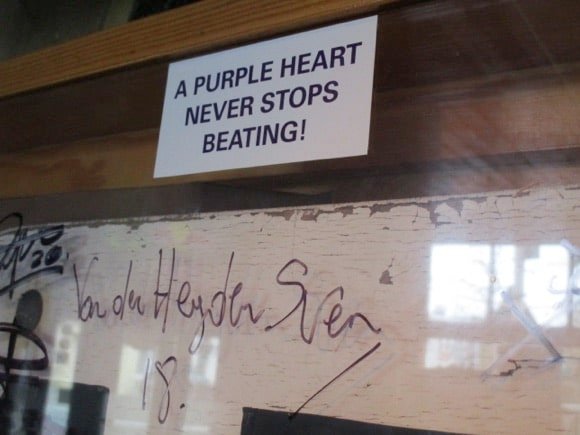

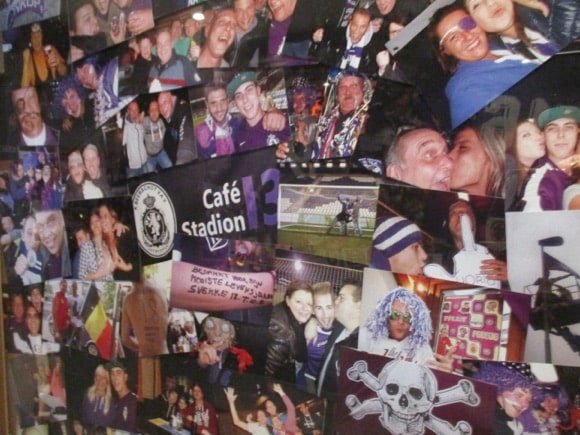

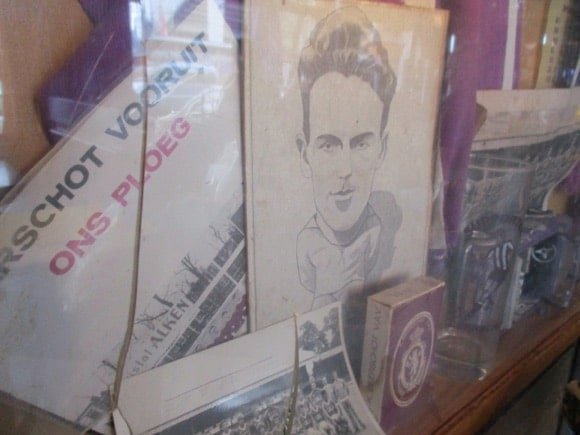

More focused on the colour purple, just past the stadium at the junction of Stadionstraat and Atletenstraat, the Café Stadion worships at the altar of Beerschot, a framed display celebrating Ons Ploeg in pennant, caricature and photograph. The pre-match throng need little reminding of the message of the sign above: “A purple heart never stops beating”.

If you can’t get to the bar – it’s pretty small inside – then try the Cafe Change right opposite the ground at the corner of Hockeystraat (street names here all relate to Olympic endeavours). Its terrace makes for a pleasant spot on sunny afternoons, if you can find a table.

Cashless outlets inside the ground dispense Jupiler beer and standard snacks. For a pre-match meal in the affordable Thema Café or finer dining in the Museum XIII restaurant of the first floor of the building near the main entrance, reserve through peter.caubergh@beerschot.be.