A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

lNo longer masters of Europe, FC Barcelona are at least masters of their own destiny. As their motto says, ‘More Than a Club’. With nearly 150,000 members and more political clout than most, Barça have put their faith in the return of former Catalan MP Joan Laporta as club president.

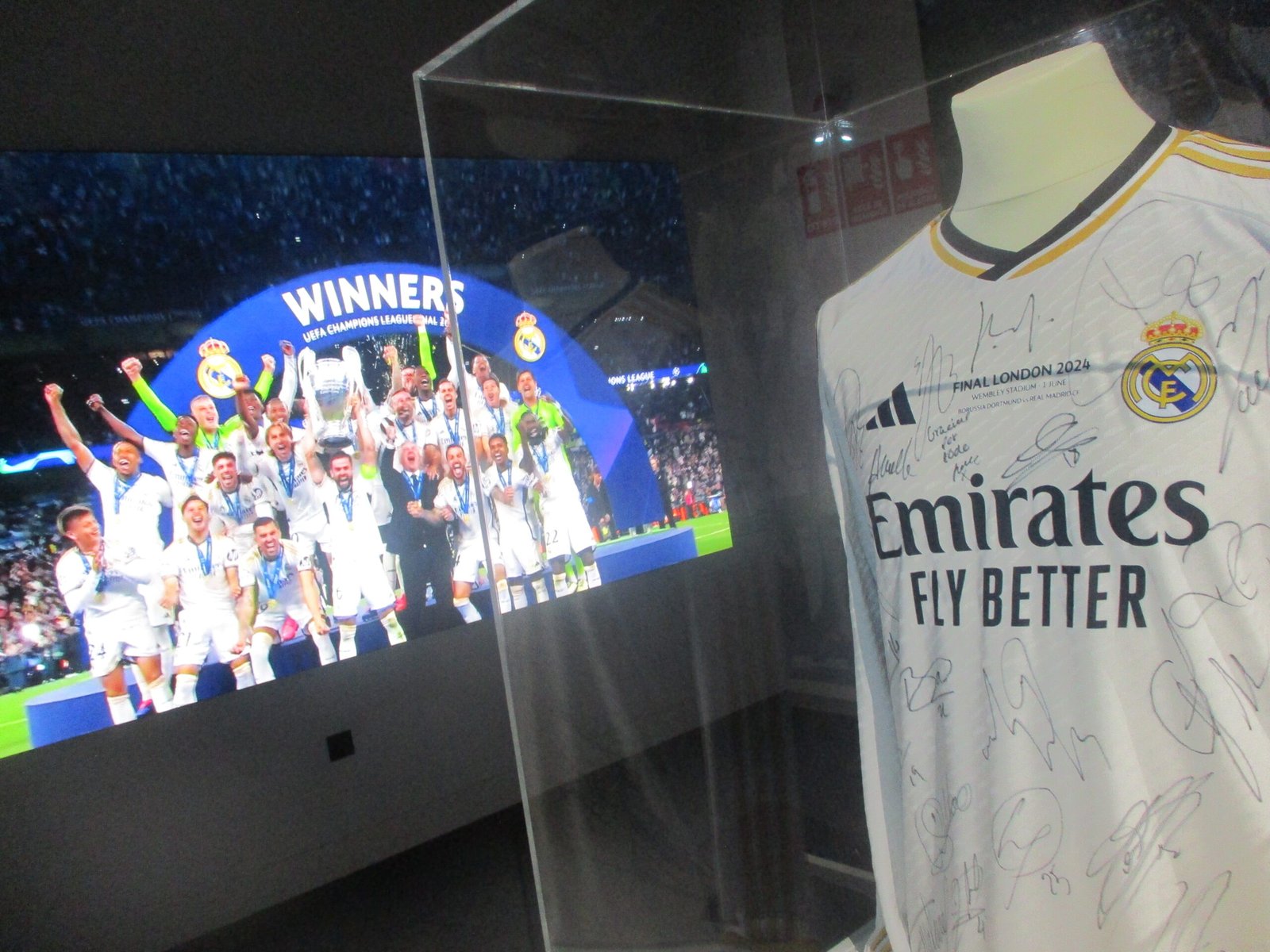

The man who oversaw the rise of one of the greatest club sides in football history, graduates from Barça’s own La Masia academy, initially looked to hone of its number to turn the ship around. Along with his midfield partner Andrés Iniesta and mercurial forward Lionel Messi, playmaker Xavi elevated Barcelona to unprecedented dominance. For a golden decade of four Champions League trophies, Barça became a huge global industry, filling cinemas for titanic El Clásico clashes with Real Madrid and shifting merchandise across the world.

As coach, Xavi helped revive the club that threw it all away, status, reputation and Messi, through mismanagement. Winning the title in 2023, the Catalan then caved in to the pressure that comes with the Barça job, making way for Bayern coaching legend Hansi Flick to step in and win the double in 2025.

Finances remain tight but Barça are at least a credible force once more. Whether now is the best time for a major rebuild of the club’s iconic stadium, the Nou Camp, and a three-season sojourn at the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys atop the heights of Montjuïc, is another question.

FC Barcelona fly the flag for Catalonia, the economically powerful region whose language and culture were suppressed under Franco until the dictator’s death in 1975. Founded by Swiss Hans Gamper (‘Joan Gamper’) in 1899, FCB wear blue and grenadine (‘blaugrana’ in Catalan) probably taken from FC Basel, another club Gamper founded. Of Barça’s 60 managers, more than half have been foreigners.

The first one Gamper hired was Jack Greenwell, who coached the great pre-war side that featured Josep Samitier, Ricardo Zamora and Ferenc Plattkó. Rampant Catalan nationalism at the Les Corts stadium built by Gamper caused the authorities to close it down. Cash-strapped to Gamper later killed himself in the wake of the Wall Street Crash.

Following the Spanish Civil War, the ground witnessed the rise of another great Barça side, with László Kubala at the helm. His statue standing proudly today outside the Nou Camp, this Budapest-born forward of Hungarian and Slovak descent could have risen to fame alongside his Magyar contemporary, Ferenc Puskás, but for war and geopolitics. Skipping borders and swapping passports, Kubala played only three games for Hungary before finding his way to Barcelona.

For Franco, the arrival of a poster boy who had rejected Communism for right-wing Spain, this was an opportunity not to be missed. Kubala was soon granted another nationality and 19 caps for his adopted country. For Barcelona, Kubala spearheaded a golden age of post-war football.

Crowds flocked to Les Corts to see him play, so much so that the club had to build a bigger stadium, the Nou Camp. When Puskás needed money to bring himself and his family over following the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, Kubala helped him find it. He then persuaded Barça to sign his compatriots Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor, members of the great Hungary side of the early 1950s.

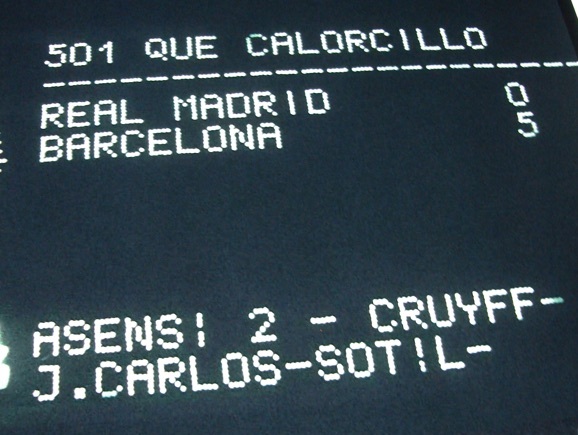

Rivalry with Real Madrid became gladiatorial. Favoured by Franco, Real were always just that one step ahead. Barça had Brazilian Evaristo, Real Di Stéfano. Barça won the first two Fairs Cups, Real the first five European Cups. The last was won in 1960 after two epic semi-final victories over Barcelona for which cautious manager Helenio Herrera had refused to play Kubala.

One of them had to go. Herrera duly left for Italy. Kubala returned to help Barcelona avenge that defeat the following season, knocking Real Madrid out of the European Cup for the first time. The stage was set for Barça to assume Real’s mantle. With Spanish forward Luis Suárez in his prime, and the European Cup beckoning, Barcelona took the lead against Benfica in the final, only to fall to a younger, stronger side. Suárez followed Herrera to Inter, Kubala retired.

Despite the arrival of Johan Cruyff and Diego Maradona, it would be 1986 before Barça made another European Cup final, a shock defeat to Steaua Bucharest on penalties.

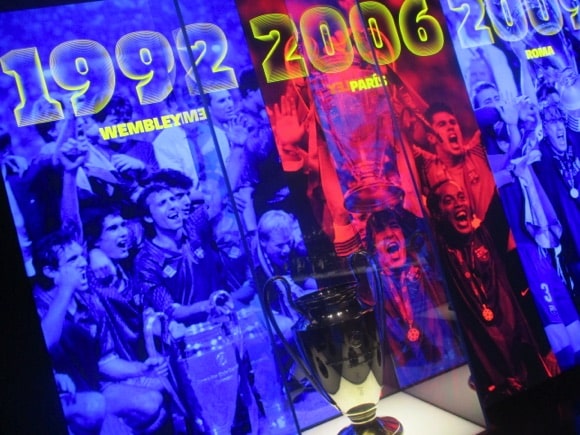

It was Cruyff who created the next great Barça team, club president Josep Núñez setting up the La Masia academy upon Cruyff’s prompting. Cruyff gave equal emphasis to key foreign stars – Ronald Koeman, Michael Laudrup, Hristo Stoichkov – as to local Catalans, particularly the young midfield orchestrator Pep Guardiola. Barça won the Spanish league four times running, and in between, that long-sought European Cup in 1992.

A repeat of Barça’s Cup Winners’ Cup triumph over Sampdoria in 1989, the Wembley win was a watershed. The last European Cup before it became the Champions League, it occurred shortly before Barcelona held the Olympic Games to become a global metropolis. It marked a last great Dutch-engineered triumph for a side playing in bright orange, the game settled by a screamer of a free-kick from Koeman.

Most of all, the lifting of the European Cup 32 years after Barça lost to Real in the semi-final was a triumph for Johan Cruyff and the attack-minded, passing tactics practised by the Ajax side he had led to three European Cups as a player. This same approach was taken by Cruyff’s playmaker, Pep Guardiola, and adopted to successful effect at the Nou Camp nearly 20 years later.

Cruyff’s Dream Team was badly beaten by Milan in the final two years later. Cruyff and Núñez fell out but the Dutchman remained behind the scenes to advise on major decisions. Fan group Elefant Blau, headed by local politician Joan Laporta, pushed out Núñez, then Cruyff pushed Laporta to presidency.

Despite a string of world-class Brazilians – Romário, Ronaldo, Rivaldo, Ronaldinho, Deco – Barça only managed one more Champions League trophy, beating Arsenal in 2006. A pressured Laporta brought in an untried Guardiola as coach, who duly achieved the treble in his first season of 2008-09.

Dismissing Deco and Ronaldinho, Guardiola created one of the finest sides in football history, whose midfield passed the opposition off the park. Messi justifiably assumed the once-in-a-lifetime status previously reserved for Pelé and Maradona, while the creative industry of Xavi and Iniesta made Barça (and Spain) almost unbeatable.

It wasn’t just the 14 trophies in four years under Guardiola – it was how they were won. Immaculate passing football (tiki-taka) was executed by the world’s best mainly raised at the club’s academy of La Masia.

One slip to Real Madrid and narrow semi-final defeats to Internazionale and Chelsea apart, Barça swept all before them at home and abroad. Perfection proved too much, Guardiola bowed out, his assistant Tito Vilanova kept the same side and won the league by a mile. Then came Neymar. After a drawn-out transfer saga, one that would have serious repercussions, the 21-year-old Brazilian needed time to set La Liga alight.

The forward line of Messi, Neymar and incoming South American Luis Suárez overshadowed even the side that Pep built. After Guardiola, already a high-water mark for European club football, FCB came good again, playing as imperiously as at any time in their history. Fronted by the dream trio, Barça gained a seventh league title in ten years, a Copa del Rey and a fifth Champions League/European Cup, all in 2014-15.

Providing able supporter were incoming old boy Luis Enrique as coach and unsung midfielder Ivan Rakitić. It was the quick-thinking Croat who scored the opener in the Champions League final against Juventus.

Incoming club president, Barcelona-born entrepreneur Josep Maria Bartomeu, had already been making big promises, underlining €600 million plans for an expanded, covered Nou Camp stadium, with an overall capacity of 105,000, to be built in stages between 2017 and 2021.

Ever so slowly, though, the roof was caving in. An investigation by the tax authorities into Neymar’s transfer put the heat on Bartomeu, vice-president at the time of the agreement. On the pitch, without a Qatar-bound Xavi, Barça had just enough to retain their title in 2016, 40 league goals coming from Suárez, 59 (!) in all competitions. In the game that mattered, however, Barça had lacked the savvy to overcome Atlético Madrid. An all-Spanish Champions League final would take place without them.

Approaching 30, Messi knew that chances to win the Champions League again would not come around too often. The following year, willing his team to overcome a 0-4 deficit against Paris Saint-Germain to engineer an improbable comeback 6-1, he then saw Barça meekly surrender to Juve in the next round.

Four days later, he destroyed Real Madrid in the Bernabéu in a Clásico for the ages. In a night of compelling drama, Barça nicked the game 3-2 and relit the title race thanks to a millimetre-precise strike on 93 minutes by the Argentine master. This was La LIga in its prime, an epic contest of the world’s very best at the top of their game. The overall winners, though, were Real, who took a first title in five seasons.

Scorer of 45 goals in all competitions in 2017-18, 34 in the league, Messi enabled Barça to overcome the €222 million (!) sale of Neymar to Paris Saint-Germain and win back the Spanish title.

Bartomeu, meanwhile, was squandering the windfall without bolstering an ageing midfield and defence. A 3-0 collapse to Roma in the Champions League was followed a year later by a similar but more dramatic second-leg reversal at Liverpool. Messi sat in tears in the Anfield dressing room afterwards, almost missing the plane home. With Iniesta having left Barça for Japan earlier in the season, the writing was on the wall.

The trophy-less Covid-hit campaign of 2019-20 began with the unwise purchase of Antoine Griezmann from Atlético for €120 million and ended in farce with an 8-2 defeat to Bayern Munich in the Champions League.

The last two goals in the rout came from Barça loanee, Philippe Coutinho. Suárez was then allowed to go on a free to rivals Atlético, Rakitić to Sevilla for next to nothing. The club that had conquered all and filled its tills with cash for Neymar was now a laughing stock.

Bartomeu lasted until a home defeat in El Clásico in October 2020. Stop-gap coach Ronald Koeman rallied a broken side, stalwart defender Gerard Piqué taking a pay cut to play. Messi showed glimpses of magic, as did incoming teenager Pedri in a 19-game unbeaten streak in the league, but Barça were steamrollered by PSG in the Champions League.

A 2-1 home defeat by Celta Vigo in May 2021 ended any mathematical chances of the title and proved to be Messi’s last game. He left the pitch of an empty Nou Camp, head bowed, having scored the only goal to make him top league scorer for the season. Three months later, he gave a tearful press conference announcing his departure for Paris. No farewell match, no gala, after 672 goals in 778 games.

Telling defeats to Bayern and Benfica in the Champions League spelled the end for Koeman. Incoming old boy Xavi was unable to prevent a slide to the Europa League but persuaded promising young Spanish international forward Ferran Torres to join bright teenager Gavi and an ever more accomplished Pedri in the Barça ranks.

Next arrived age-defying Polish star Robert Lewandowski to top the scoring charts and point towards a more promising 2022-23 than seemed possible when Messi bowed out before 2021-22. Barça put together a long winning streak either side of defeat in El Clásico to run away with 27th league title.

Financially, however, despite a controversial sponsorship deal with Spotify, the club is in a deep hole, which makes the decision to instigate a complete rebuild of the Nou Camp mystifying. Until the start of 2025-26, Barça will play their home games at the Olympic Stadium way up on Montjuïc, to much smaller crowds used to seeing their football in the city centre. Attractions such as the museum and main club shop remain at the Nou Camp for the time being.

On the pitch, ironically, as promises of a Nou Camp reopening stretched every deeper into the 2024-25 campaign and beyond, a fast, young Barça team under Hansi Flick set La Liga and Europe alight. Characterised by teenage sensation Lamine Yamal, quite simply the most exciting player in the world, Barcelona clocked up 100+ goals with barnstorming wins at the Bernabéu, 4-0, and at Benfica, 5-4.

Given a new lease of life at 36, veteran Pole Lewandowski clocked up 40+ goals for the season but the real story was Raphinha. Hardly prolific under Xavi after his arrival from Leeds in 2022, the Brazilian international was given a central role and the captain’s armband by Flick, responding with assists and goals galore, many of them vital ones.

This was never better illustrated than in the two fixtures that defined Barça’s season in May 2025. Chasing the treble, with passage to the Champions League final at stake, the Catalans had surprisingly been held in check by a tough Inter side at Montjuîc, 3-3. In the decider in Milan, a semi of epic proportions, Raphinha seemed to have edged out the hosts at 3-2 as extra-time beckoned.

A shock strike by Inter veteran centre-back Francesco Acerbi deep into stoppage time then took the game into an extra half-hour, much to the delight of all watching neutrals. The Italians duly swept into the final 4-3 on the night, 7-6 on aggregate, leaving Barcelona to pick themselves up off the San Siro turf and prepare for a title showdown with Real the following weekend.

Seemingly unphased by conceding two early goals, Barça came roaring back to wrest the league crown off the champions thanks to a spectacular curler from Yamal and a decisive brace by Raphinha. Repaying Flick’s faith in him severalfold, the former Leeds man had not only hit 34 in all competitions but had established himself as one of the game’s global elite.

As celebrations broke out around a surprisingly raucous Montjuïc, Barça 4-3 winners and the title all but assured, it felt like a new era had begun at the Blaugrana, with a new Nou Camp to move into and a future being illuminated by youngsters Yamal, Pedri and Cubarsi. But Flick was quick to congratulate veteran Polish keeper Wojciech Szczęsny, plucked out of retirement to play a key role in a memorable campaign.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

Barcelona’s move to Montjuïc shortly before the 2023-24 campaign does not mean that their iconic stadium, the Nou Camp, is out of bounds, far from it. For the time being, visitors can still enter the Mirador above the club’s main store at the venerable old ground and watch as piles of rubble are heaped up by huge diggers across the pitch that Messi, Cruyff and Kubala once graced.

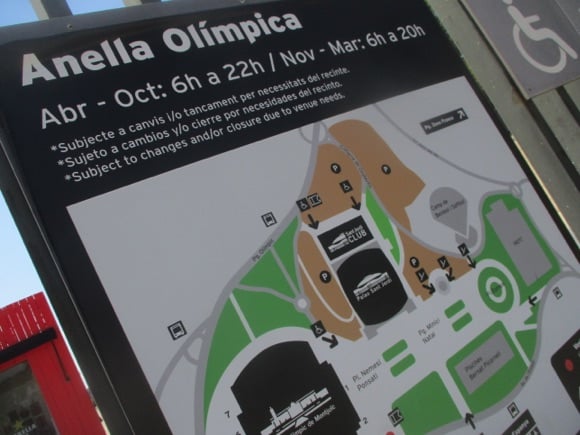

it does mean, however, that to watch Barça in action at home until the end of 2025-26, you’ll have to scale the heights of Montjuïc south of town, accessible by funicular, bus or cable car, for a less intimate experience at the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys.

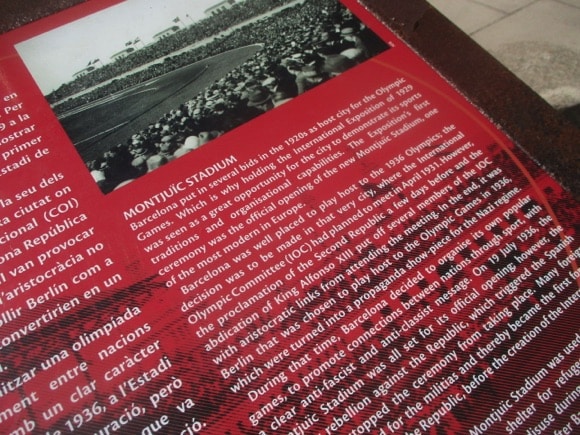

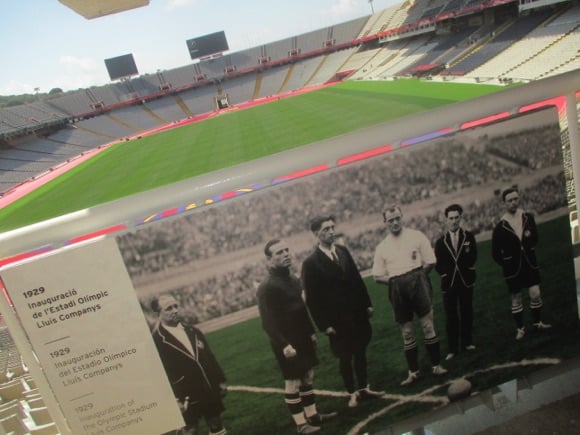

Built for the 1929 International Exposition in the striking, Modernist style of architect Pere Domènech i Roura, it embodies the optimism of the era between the wars, before Nazism and the Spanish Civil War came to the fore. Indeed, after inaugural events including a 4-0 win by a Catalan XI over Bolton Wanderers, it would have hosted the 1936 People’s Olympiad in protest against the Games being staged in Hitler’s capital had conflict not broken out in Spain that July.

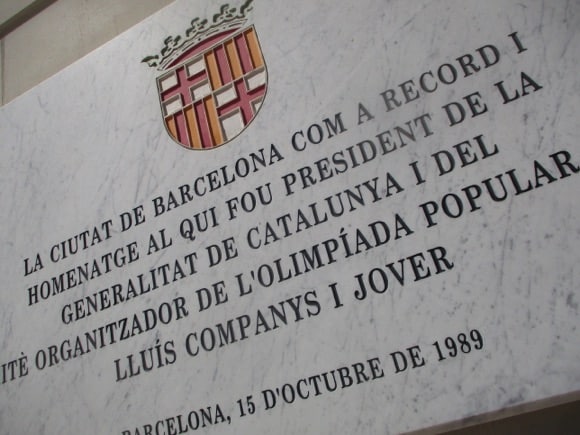

Athletes either fled or stayed to defend the Republican cause. The stadium later took the name of the president of Catalonia, a lawyer named Lluís Companys, captured by the Gestapo when exiled to France, sent back to Spain and executed in 1940. A seemingly meek intellectual, when facing the firing squad, Companys refused a blindfold and shouted ‘For Catalonia!’ in his final seconds. He is buried at Montjuïc Cemetery.

Ironically, Spain’s national team had welcomed Germany here that February, the third of three pre-war friendlies played at Montjuïc. The Spanish FA continued to use the stadium in the late 1940s – Irish legends Johnny Carey and Paddy Coad were in the ROI side that lost 2-1 here in 1948, the crowd given as 65,000 – but the venue otherwise became infamous as a refugee camp for economic migrants from the south or locals who had been on the losing side in the Civil War.

The stage for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Mediterranean Games of 1955, and the Spanish Cup final between city rivals Barcelona and Espanyol two years later, the stadium was a crumbling anomaly when the International Olympic Committee met in 1986, half a century after the would-be People’s Olympiad. With local man Juan Antonio Samaranch the IOC president, all the stars were aligned for the Catalan capital to host the Games of 1992.

The event not only transformed the city but also the stadium, Milanese architect Vittorio Gregotti preserving the palatial façade and Marathon Gate but creating an entirely new arena within, a sunken bowl holding 70,000 seats. Across the Montjuïc complex, past the indoor Palau Sant Jordi, the diving and swimming events took place, memorably backdropped by Barcelona’s vast cityscape.

Given the recent Fall of the Berlin Wall and acceptance of Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia-Herzegovina into the Olympic fold, it felt like the kind of ambitious new beginning Companys and his compatriots might have wished for 1936.

Despite this triumph, the future of the Olympic Stadium remained uncertain until homeless Espanyol moved here five years after the Games, having sold Sarrià and the land around it. Few remember this era with particular fondness apart from, perhaps, Lionel Messi, who made his debut here in the derby of 2004.

It was also around this time that Spain returned to play a friendly or two, and bands such as the Rolling Stones used Montjuïc for big-stadium rock.

Barça’s decision to move here during the Nou Camp rebuild can’t have been an easy one. The pre-season friendly against Tottenham in the summer of 2023 was the first football match staged here in 14 years, and despite the stadium being done out in FCB livery, it still feels very much like exile. The conversion from an occasional athletics stadium and music arena has cost the cash-strapped club €20 million, with a €50 million drop in revenue expected for each of the three seasons the Blaugrana scale the heights of Montjuïc.

Capacity is officially 54,000, just over half that of the Nou Camp, though only 50,000 seats offer full visibility of the action. On non-match days, the stadium is open 10am-6pm (Nov-Mar until 5pm), so you may enter the grand main entrance, gaze into this great bowl, study the archive photos on display at this northern end of the stadium and enjoy a drink at the Olympic Sport Café.

Once a vast three-tiered bowl with a thin, vertiginous fourth fringe by each scoreboard, the Nou Camp was inaugurated on 24 September 1957 during the post-war boom in Spanish football. With Kubala and other stars regularly attracting 60,000 fans to the cramped Les Corts, the management needed a modern arena. The first stone was laid in 1954 – in front of 60,000 fans. Three years later, with Handel’s ‘Messiah’ blasting out, one of the world’s finest football temples was unveiled.

It then became a refuge for Catalans looking to express pride in their region being repressed under the Franco regime. Ironically, Barca’s greatest triumph over their bitter rivals, the Cruyff-inspired 5-0 win of 1974, took place at Real’s Bernabéu.

In order to prepare for the 1982 World Cup, stadium capacity was increased to 115,000 with the addition of a third tier. In 1998, standing areas were converted to seating, reducing the capacity to just under 100,000. Many of those packed in for the Manchester United-Bayern Munich Champions League final of 1999 had already left the ground before United’s Teddy Sheringham and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer famously reversed the scoreline in stoppage time.

Still luxuriating in the trophy-laden Messi era, the Nou Camp attracts visitors to the club museum, stadium tours replaced by the immersive experience of being surrounded by FCB history on touchscreens and huge video boards, culminating in a sensaround farewell to the old legend. The final stop shows how the new venue will look, roof, 30,000 solar panels, 105,000 seats and all – at a cost of €1.5 billion and spiralling.

Despite the City Council approving an extension to 24-hour construction on the new arena in April 2025, Barcelona weren’t able to host El Clásico there the following month, the title decider filling Montjuîc to capacity. When Barça do move into their redeveloped home, probably in September 2025, it will only be at 65% seating capacity.

While this will be increased in phases, the roof won’t be added until the summer of 2026 – at least in time to prepare to co-host the 2030 World Cup.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

The easiest way to reach Montjuïc is either by funicular from Paral.lel, with a special match-night service beyond it usual 8pm winter closing, or by cable car from the Mirador de l’Alcalde or Castell de Montjuïc castle on the port side of Montjuïc Hill.

While the funicular is swift and functional, the journey over in a couple of minutes, the service can be used with regular transport tickets and passes – plus Paral.lel is on lines 2 and 3 of the city’s metro network, the funicular entrance built within the same station. While spectacular, the cable car costs €11 one-way, €15 return, with 10% discounts if booked online. The journey covers 750 metres.

The cable-car stations are only accessible on the special red Barcelona Bus Turístic or by regular lines 50 and 55. Near the stadium, the stations for each type of transport are alongside each other – head left along Avinguda Miramar/de l’Estadi, past the Olympic Museum, to reach the stadium in 10mins.

Alternatively, you can walk up from Plaça d’Espanya (red L1, green L3 metro lines) in town, gliding to the palatial Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya via escalator, then up several flights of stairs to the stadium. Improved lighting has been fitted especially for Barça’s stay. Allow 20-30mins from leaving Plaça d’Espanya metro station.

The Nou Camp is north-west of Sants train station, surrounded by three metro stations: Collblanc (blue L5); Les Corts, and Maria Cristina (both green L3). Collblanc gives access to the bars of Riera Blanca and is an easy, direct hop from Sants.

Bus 56 runs closer, right by the bars of Riera Blanca, and links with Sants and focal squares of Espanya and Catalunya.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Tickets go on sale ten days before each match from the Oficina de Taquillatge at Accès 14 (Mon-Thur 9am-1.30pm, 3.30-6pm; Fri 9am-2.30pm; Sat on match weekends 9am-1.30pm; match days from 11am). Locals also hang around Accès 14 to offload any spares. Tickets are also available online.

Depending on the price category of the opposition, a seat in the best spot (1a/2a grada) in the main stand (tribuna) over the halfway line will cost €140-€180. Higher up (3a grada) is a few euros cheaper.

Facing this, the lateral is similarly graded into tier prices (€100-€150). Behind the goals, the three tiers break down into price categories from €70-€90. The cheapest places are gol no numerat, general access, at €59.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

Along the pedestrianised walkway on the west side of the stadium by the Palau Blaugrana indoor arena, the Botiga Oficial del Barça Camp Nou (Mon-Sat 10am-7pm, Sun 10am-4pm) is a huge, two-tiered affair stocking shirts for the 2024-25 campaign designed in halves in the storied shades of blaugrana.

Sponsors Spotify have their logo front and centre, with the more updated version the only splash of colour – red – on the all black of the away strip, apart from a flashes of blaugrana down the sides. Third choice is lime, forever associated with the epic semi-final of the Champions League against Inter at the San Siro.

LEGO models of the Nou Camp go for a staggering €300+, long-shirted retro shirts with button-up collars celebrate the club’s foundation year of 1899, or there are away tops from the 1980s of bright yellow with a single blaugrana stripe down one side.

You’ll find other outlets on the Ramblas (No.124) and Passeig de Gràcia (No.15), both open Mon-Sat 10am-9pm. There are more stores at Universitat (Ronda de la Universitat 37), near the Sagrada Família at Carrer de Mallorca 406 (both Mon-Sat 10am-9pm) and at both airport terminals (daily 10am-9pm).

tours & Museum

Explore the club inside and out

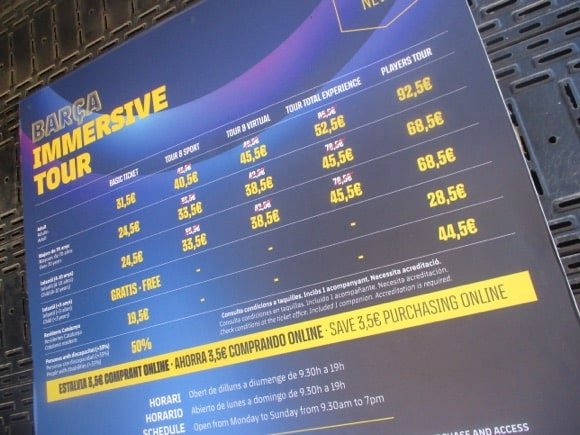

There are various ways to treat the kids to the Camp Nou Experience but the basic tour/museum purchased online is €28, €21 for 4-10 year olds and over-70s. Under-4s get in free. Throw in around €5 for the VR glasses, €3 extra if you’re paying on the door and that’s well over €100 for a family of four. Plus they’ll bombard you with photo opps as you walk round.

These days you can’t just buy a museum ticket, it’s plus tour or nothing – so bite the bullet, take in the interactive room, the Messi section, the Cruyff area and trophies the size of Jodrell Bank.

The stadium’s breathtaking of course, but the home dressing room is off-limits. Note the black Madonna chapel by the players’ tunnel.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

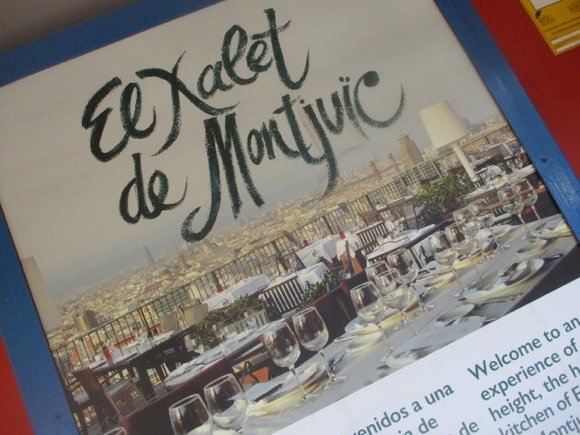

While Barça play atop Montjuîc, probably until September 2025, you’ll find a couple of pre-match drinking and dining options as you arrive by cable car or funicular. Directly opposite either station on Avinguda Miramar, upscale restaurant El Xalet de Montjuïc makes full use of its panoramic setting, although you’ll be paying for the view as well as the top-quality Spanish cuisine.

For the same vista in more down-at-heel surroundings, head further along the avenue towards the stadium, looking for the sign that says ‘Bar Marcellino‘. This consists of a scattering of tables and chairs in the open air, by a simple outlet dispensing standard drinks and snacks at regular prices.

Immediately below is an all-weather football pitch – beyond, the whole cityscape of Barcelona spreads at your feet, punctuated by the signature spires of the Sagrada Família. If Marcellino is a bit too rough-and-ready, cross the road and make for the Olympic pool complex just past the stadium.

Family-friendly bar/restaurant El Sabor de Picornell serves those using the pool shimmering beneath the terrace, the skyline evoking memories of the 1992 Olympics and its diving events filmed so spectacularly for worldwide TV.

The bar itself is pleasingly unpretentious and affordable, a thick slab of tortilla, tomato-covered bread and a small beer barely costing €10. Note the honorary roster of 1992 medallists on the wall by the entrance.

At the stadium itself, Estrella Damm is served at the fire-red La Guingeta bar on the pool side of the ground, at various match-day kiosks and at the Olympic Sport Café tucked into the main stand.

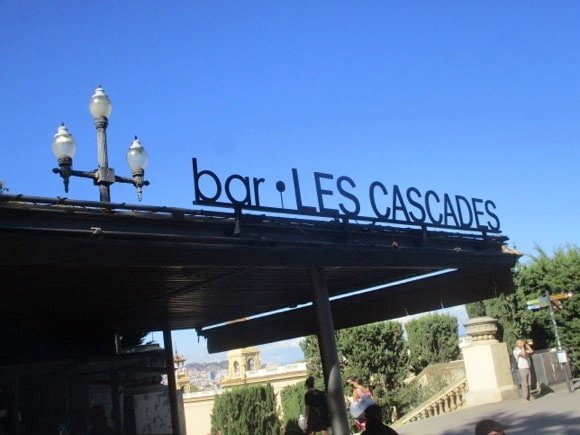

If you happen to be walking up from Plaça d’Espanya, Bar Les Cacades at the foot of the palatial National Art Museum provides a handy alfresco pitstop.

Back at the Nou Camp, pre-match bars line both sides of Riera Blanca, south of Travessera de les Corts, between Collblanc metro and the Nou Camp. Sadly El Rincón de Viti and its wall of framed Barça photos are no longer with us but still offering Galician cuisine, on the same strip, the Casa Ferreiro nearby is a handy place to catch the game on TV if you’ve not been lucky enough to get in. Now featuring an open kitchen, it’s trying to play more to its culinary credentials. Watch the bill at the end, though, as those tapas can quickly add up.

Opposite, El Cargolet Picant is an upscale eaterie while the sun-catching seats outside Bar El Rellotge also provide a pre-match terrace.

Still on the same side of the stadium, a little further along and so slightly less crowded, the Bar Avinguda (Carrer del Cardenal Reig 26) puts a big TV in the window for pavement drinking and snacking, with press clippings of famous Barça victories framed inside.

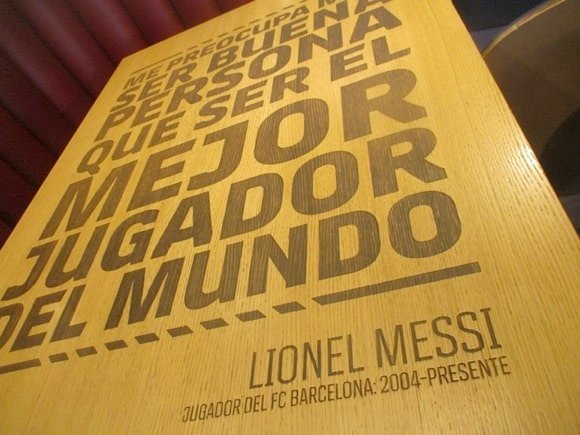

The best pre-match destination stands at Carrer de Benavent 7. A living testament to the three Hungarians who starred for FCB in the 1950s – Kubala, Kocsis and Czibor – Futballárium is overseen by Péter Büki, a Haladás fan from Szombathely.

Fans gather for goulash and pálinka brandy before the 200-metre stroll to the stadium. There are plenty of draught beers, too. By way of introduction, you might want to bring a scarf of any club who play in green – it’s a Haladás thing – though wall space is pretty limited by now.

Since opening in 2014, Péter and the close-knit circle of family and friends who help him run the place have welcomed a number of famous names, including Peter Shilton and Barça legend Andrés Iniesta, whose signed memorabilia (including his own wine) shares display space around the back bar.

Even closer to the ground, on Travessera de les Corts between the NH Rallye hotel and the stadium, there’s another row of busy pre-match bars, some with pavement tables. These include San Juan, BaYo, Granja El Gol, 3 Copas and Casa Pin.

A welcome addition at the ground is the Barça Café (daily 10am-7pm), occupying a prime spot by the club shop on the pedestrianised stretch by the indoor sports arena. Tapas, burgers and charcoal-grilled meat and fish are served with draught Estrella – TV screens and FCB iconography abound, of course.

Outlets nearby include La Buti, dispensing grilled meats to families happy to rest their feet and part with more pesetas after a visit to the club shop. At the temporary entrance to the parts of the Nou Camp currently open to the public on Carrer d’Aristides Maillol, the Cal Blay gastrobar appeals to the more discerning diner, with a pleasant terrace, Players’ Square.