A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

Flagship club of the island capital of Palma, Real Mallorca have long been a steady presence in La Liga, though the European final and Spanish cups of the late 1990s and early 2000s are now a distant memory. Back then, Mallorca abandoned, neglected and then failed to sell their quaint little Lluís Sitjar ground in town, a weed-entangled testament to decades of earnest if modest football. Fans have since had to trek up to the graceless, out-of-town Son Moix.

Shorn of the running track that was the centrepiece of the Universiade student games for which it was built, the Son Moix is only now being converted for football after 20 years. Its host club, meanwhile, nearly went under in 2016, when there was talk of a return to the Lluís Sitjar, if Real Mallorca survived at all. Controversial Arizona-based entrepreneur Robert Sarver bought the club for €20 million, only to see Mallorca drop down to the third tier.

Fellow North Americans Andy Kohlberg and Steve Nash, also with connections to the Phoenix Suns basketball team, then bolstered the Palma club, which rose back to La Liga in two straight seasons. Before 2023-24, Sam Garvin, formerly a major Suns stakeholder, took over from Sarver, while ex-Chelsea star Graeme Le Saux remains on the board.

All of this is a very far cry from the club’s roots, among Palma’s well-to-do, royalists all, most with business links to Barcelona on the mainland. These entrepreneurs gathered on March 5, 1916 at the residence of fellow co-founder Alberto Elvira on Calle Ca’n Armengol to form Alfonso XIII FC. The name referred to the young monarch who had visited Palma shortly after he came of age in the early 1900s.

Other key personalities among the club’s founder was president Adolfo Vázquez Humasqué and Dr Antoni Moner Giral, a player who had taken part in the first games in the city, staged at velodromes as cycling had been the favoured sport of these pioneers. Another figure was Lluís Sitjar of stadium fame and Civil War infamy. A member of Palma’s landed gentry, Sitjar was on the club’s board of directors, then president, then replaced once the republic swept away the monarchy in 1931.

After the Reds were renamed the royal-free Club Deportivo Mallorca, Sitjar became a local councillor, before being involved in the execution of left-wing prisoners during the Spanish Civil War. He reassumed presidency of his old football club, re-renamed Real (‘Royal’) Club Deportivo Mallorca, and built a new ground a few hundred metres from their original ground, the Camp de Bons Aires.

In the pre-Civil War era, by the barracks on Carrer de General Riera, the original Mallorca had attracted the best players in Palma and dominated the Balearic Regional and Mallorcan Championships. Local rivals Baleares, today’s lowly Atlético Baleares, were invariably runners-up. The derbi palmesano between them, a third-tier affair in the 1950s and 1970s, was revived in 2017-18 during Mallorca’s brief sojourn with the lesser lights.

Mallorca’s arrival at the Sitjar-built Camp d’Es Forti in 1945 chimed with an uptick in the club’s fortunes, promotion to the Segunda and the arrival of a young Antoni Ramallets before his illustrious stint between the sticks for Spain and Barcelona. With a new stadium often packed to its 16,000 capacity, Mallorca won their second-tier group in 1960 with another famous name in goal, Ricardo Zamora, son of the legendary pre-war keeper.

Playing in what was then the world’s strongest league, the club survived for three seasons, then hopped between the Primera and Segunda while Mallorca, as an island, embraced package tourism. Holidaymakers began to find their way to the stadium, now named after Lluís Sitjar.

Despite the bump in gate receipts every August, Real Mallorca were in a dire state, even tumbling down to the fourth flight in 1978. That was exactly when Miquel Contestí stepped in, the Mallorcan entrepreneur taking over a club with only five players on the payroll and creditors, including the electricity company, knocking on the door. Contestí pulled in a favour from the then head of the Spanish FA, the Catalan Pablo Porta, and arranged a huge interest-free loan to save the club.

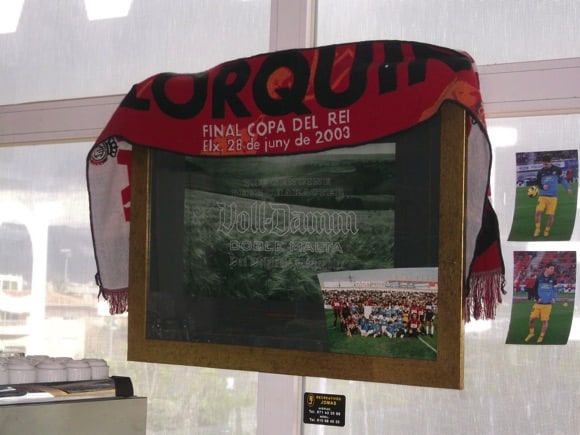

Within six seasons, Real Mallorca were back in the Primera, albeit briefly, before longer-term stints in the 1990s. While previous club presidents were of the old school, charming celebrity doctor and TV presenter Bartolomé Beltrán represented the dynamic new Spain. Suddenly, despite their now cramped, crumbling stadium, Real Mallorca became an exciting place to be. With the Balearics losing their shoddy image and players such as former Red Star Belgrade midfielder Jovan Stanković and goalkeeper Carlos ‘Lechuga’ Roa coming on board, the club finished fifth in La Liga, only losing out to Barcelona in the Spanish Cup final after a long penalty shoot-out. Roa, Argentina’s hero goalkeeper from the 1998 World Cup, converted his, but to no avail.

Most of all, there was Héctor Cúper. A chiselled Argentine centre-back who held together the defence at Buenos Aires railway team Ferro Carril Oeste in his playing days, as a coach Cúper worked miracles at little Lanús before being persuaded to cross the Atlantic and repeat the feat at Mallorca. This he duly did, taking them into Europe for the first time on the strength of that cup-final appearance and gaining revenge for the runners-up medal by beating Barcelona in both legs of the subsequent Spanish Super Cup, Figo, Rivaldo and all.

Beating Hearts in the First Round despite the lower-than-regulation goals at the Lluís Sitjar, perhaps a Cúper ruse to counteract the Scots’ aerial power, Mallorca edged their way through the Cup Winners’ Cup thanks to Argentine savvy. For their away leg, the Belgians of Genk protested the lack of space around the corner flags but still the home team prevailed. A kind draw in the quarter-finals saw Cúper’s men overcome the relatively unknown Varteks Varaždin from Croatia, whose defensive midfielder Zlatko Dalić later led his nation to a World Cup final in 2018.

Surprising star-studded holders Chelsea in the semi-final at a raucous, pulsating Lluís Sitjar, little Mallorca made their first, and so far only, European final, the last ever match in the patchwork history of the Cup Winners’ Cup. While by no means outclassed at Villa Park, Cúper’s side fell to a late Pavel Nedvěd strike for a Lazio team that also featured Christian Vieri, Roberto Mancini and Alessandro Nesta.

In Palma, too, it was the end of an era. Cúper left for more European finals with Valencia, while the Lluís Sitjar would pulsate no more – Real Mallorca headed up to the municipal Son Moix, a running track separating the pitch from the passion.

It wasn’t all gloom. That same 1998-99 season also culminated in a best-ever third place in La Liga, Carlos Roa the best keeper in the division, but the subsequent Champions League campaign ended as soon as it began thanks to a shock away-goals defeat to Molde of Norway. In the UEFA Cup, Mallorca then brushed aside Ajax and Monaco at the Son Moix, where Galatasaray came away with a result in the next round.

The last hoorah of this golden era in Mallorca’s history was a cup win over underdogs Huelva, 15 minutes of fame for the oldest club in Spain, unable to deal with the power of a young Samuel Eto’o. A year later, the Cameroon legend would be off to Barcelona.

By then, Mallorca were slipping down the table, and attracting fewer and fewer fans to the much-maligned Son Moix. In the Segunda by 2013, the club hit rock bottom with relegation to the third tier after 2017. With talk of a return to the Lluís Sitjar, even the threat of disappearing entirely, Real Mallorca had already been sold to Robert Sarver and Steve Nash, American entrepreneurs with long ties to the Phoenix Suns basketball team.

Sitting things out in the Son Moix, Mallorca won a promotional play-off to clamber out of the third at their first attempt, then reversed a 0-2 first-leg defeat at La Coruña to beat the Galicians 3-0 in the home leg and secure a return to La Liga in 2019. Perhaps as importantly, after 20 years, discussions with the City were reaching a conclusion over the sale of the old Lluís Sitjar site.

In May 2023, it was announced that the council had bought 83% of the land, the income allowing the club to invest in converting the Son Moix into something more resembling a football stadium. Phase three of the works begins in January 2024. On the pitch, Mallorca maintain a mid-table presence in La Liga under former Mexico manager Javier Aguirre, who stepped in when relegation threatened in 2022.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

The Estadi Mallorca Son Moix, on the wrong side of Palma’s urban ring road, the Autopista Via de Cintura, is currently benefitting from a significant redevelopment after two decades of disdain. Built for the student Universiade of 1999, the stadium was immediately given over to Real Mallorca as their new home, while remaining in the hands of the City.

The result was 20 years of disgruntled and dwindling crowds as the tenants failed to reach the same heights, or generate anything like the same passion, as when they were playing at the intimate Estadi Lluís Sitjar in town. At one point, Mallorca even considered moving back but good sense prevailed and the old site was eventually sold.

The club now has the funds and council backing to redevelop the Son Moix, removing the running track and bringing spectators more than eight metres closer to the action. Capacity is a shade over 23,000, adequate for a club whose natural habitat is mid-table in La Liga.

Both the Fondo Sur and the Fondo Norte behind each goal will have been fully remodelled by the time the revamp is complete in 2024, the home north end fitted with 3,000 extra seats before the 2023-24 season so that fans are as close as 7.5 metres from the pitch.

While construction of the stadium is still ongoing, visiting supporters enter through Gate 10 near the Fondo Norte, as opposed to the regular Gate 6 by the Fondo Sur.

The Tribunas Sol (East) and Cubierta (West) are twin-tiered, the upper covered West Stand with an uncovered one (Descubierta) in front of it.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

Three buses run from the main transport hub of Plaça d’Espanya-Estació Intermodal by the city centre to Son Moix. The nearest stop to the stadium is Camí dels Reis-Estadi de Son Moix on line 6, but it’s infrequent during the week, every 40mins, and doesn’t run at all at weekends.

The number 8 is a better bet, running every 12-15mins until late in the evening, stopping at Son Moix near the stadium complex on main Camí de Sa Vileta, then just past the roundabout for the stadium at Camí de Sa Vileta-Son Peretó.

An alternative is bus 9 that stops on the other side of the stadium at Can Valero Zona comercial, but again is pretty infrequent. A taxi should cost around €10 from town.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Many of the 23,000 seats at the Son Moix are taken by season-ticket holders, or socios. Your best bet is to book online as early as possible, although the club only distributes for one home match at a time.

To buy in person, the ticket windows at the stadium open Mon-Thur 9am-2pm, 3.30pm-6.30pm, Fri 9am-3pm. To see about availability and match-day sales, email taquillas@rcdmallorca.es or phone +34 971 221 535.

The best seat in the house, in the Altas in the Tribuna Oeste, will cost you over €100. One in the Bajas or Laterales will be slightly cheaper. Opposite in the Tribuna Este, prices are similarly structured. Admission to the home Fondo Norte will be the same across the board, around €50 depending on the opposition, while in the Fondo Sur, it’s slightly cheaper.

There are substantial discounts for over-65s and under-21s, and significant ones for infants.

Prices rise horrifically for the visit of Barcelona or Real Madrid, when you’ll be forking out around €160-€180 for a seat in one of the long sideline stands.

Note that Mallorca are one of 14 top-flight clubs to offer at least 300 places to away supporters at €30 or under, sourced through the visiting club.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

The club has two stores, one at the stadium (Mon-Sat 10am-8pm, match days) between the Fondo Norte and Tribuna Oeste, and one in the city centre (Mon-Sat 10.30am-8pm, Sun 11am-7pm) at Plaça de Cort 7.

The current iteration of the storied vermillion shirt has thin white bands across it, the back pure red but for the player’s number. Change strip is grey and black hoops with thin bands of red, third choice a distinctive sea green with sky-blue sleeves, or rather ‘hyper turquoise-chroline blue inspired by the idyllic coves of the Balearic island’. It may not seem so idyllic if they have to wear it on a muddy night in the driving rain of the Basque country.

T-shirts feature the club name with a huge Nike tick above it or ones with fold-down collars with the RCD crest prominent.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

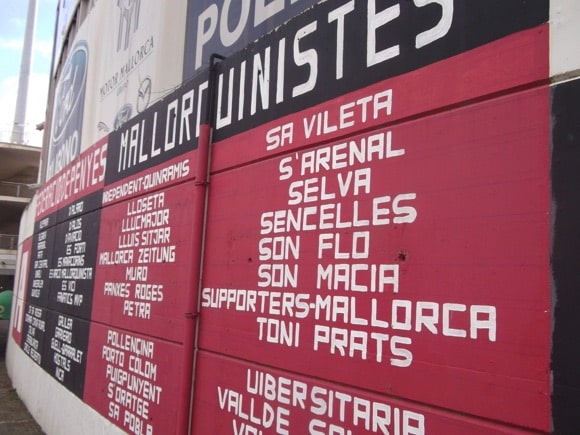

Its long terrace set between the indoor arena and the football ground within the sports complex, the Cafeteria Son Moix does the basic things right, providing standard Catalan dishes and drinks, sometimes tailoring the menu to suit the match that day. Its gradual transformation from everyday football bar to mid-range eatery chimes with the more corporate feel of the Estadi de Son Moix itself.

The stadium has its own RCD-themed bar, Mallorcafé, just behind the Fondo Norte and next to the club shop. Open every day from that first cortado at 8am to the last swift caña as midnight approaches, the Mallorcafé makes up for its somewhat antiseptic (though TV-blessed) interior with a lively terrace overlooked by a huge screen. Absolutely essential pre-match, it’s pretty much a one-bar fan zone. The kitchen’s decent and look out for Rosa Blanca on tap, a century-old Mallorcan brew relaunched by Damm in recent years.