A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

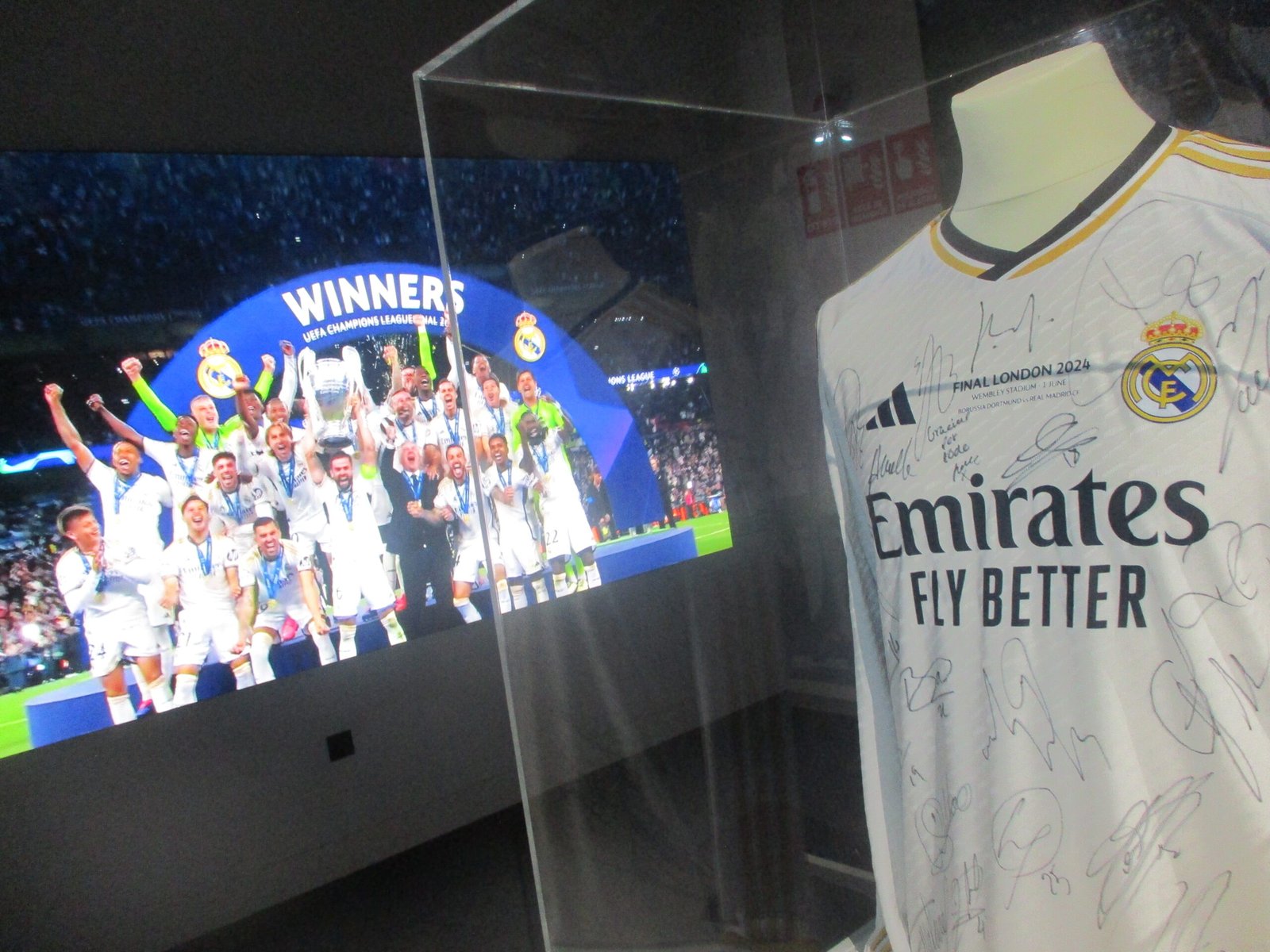

Record Champions League winners Real Madrid claimed a 15th trophy in 2024, after becoming the first side in the modern-day tournament to be crowned three in a row back in 2018. Spain’s gilded grandees not only find a way to win, they attract the game’s finest talent in order to do so.

It started with Alfredo di Stéfano, Ferenc Puskás and the five straight European Cups under the president whose vision and political connections in the Franco era established Real as a global player. The club’s stately arena, the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu, has carried his name ever since.

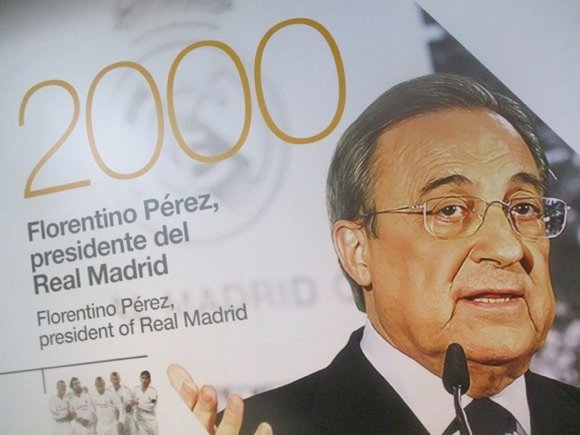

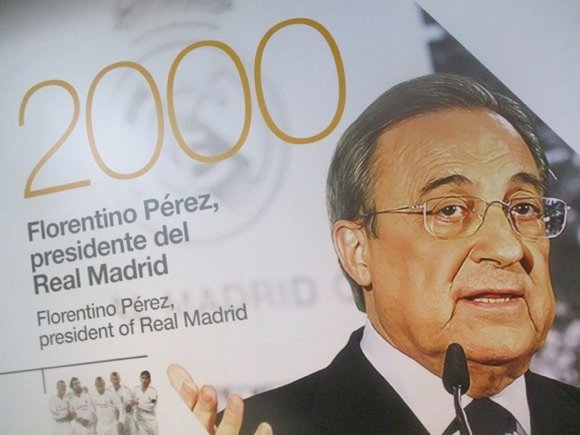

His modern-day successor, Florentino Pérez, rose to power on the promise of gathering the Galácticos of Zidane, Figo and Beckham, then, in his second term, doubled down with the arrival of Cristiano Ronaldo, Gareth Bale, Jude Bellingham and Kylian Mbappé.

The result has been a string of European Cups and Champions League trophies twice as long as any other club’s, stretching back 70 years. The marquee signing of 2024, lifelong fan Mbappé was never not going to come to Real Madrid, it was just a question of when.

For all the astronomical transfer fees and salaries, not to mention heading up the universally unpopular initiative to launch a European Super League, Pérez has been astute enough to lead Real Madrid from the mid-1900s into the later 21st century, transforming the Estadio Bernabéu into a multifunctional contemporary arena with a shiny steel exterior.

Here, almost certainly, the 2030 World Cup Final will take place. Where, some might argue, it certainly belongs – along with those 15 European Cups and Champions League trophies, and counting.

Real Madrid, their traditional all-white shirts offering the nickname of los Merengues, a glossy confectionery of egg white, have long been considered elite.

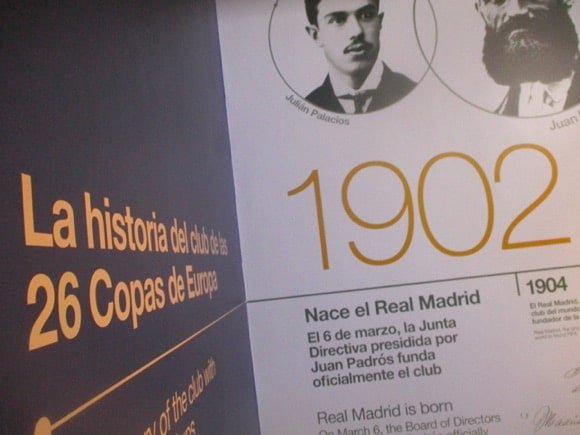

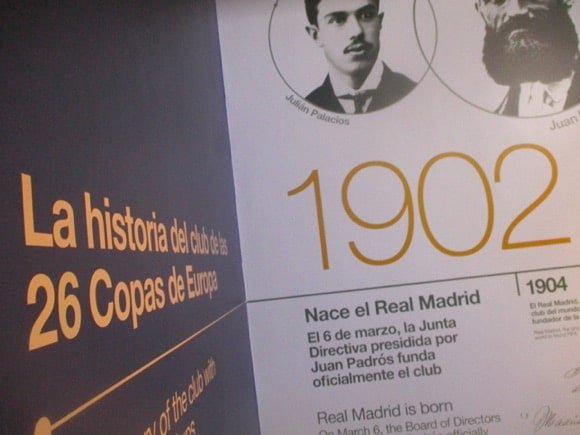

It was King Alfonso XIII who decreed Madrid FC ‘Real’ (‘Royal’) in 1920. Madrid FC had been formed from university teams Football Club Sky and New Foot-Ball de Madrid, the original members Oxbridge students from the early 1890s. The club played at various modest pitches until settling on the Campo O’Donnell by the street of the same name in 1912. A junior Madrid player called Santiago Bernabéu helped put up the fence around the pitch.

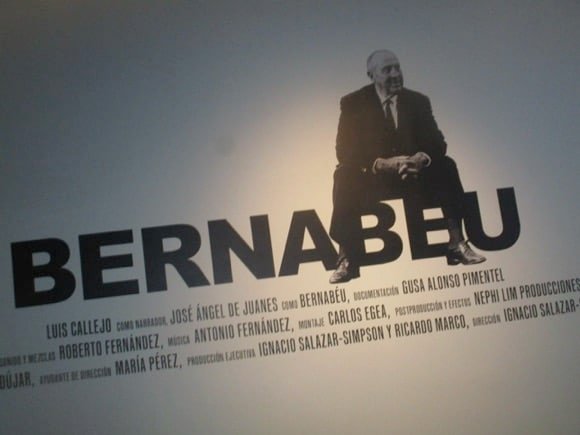

An inside-forward of some note, Bernabéu became team captain during the 1910s, surprisingly switching to play one game for Atlético Madrid in 1920 – surprising, because it was Bernabéu who built modern-day Real after serving the club as player, manager and coaching assistant for 25 years.

During that time, Real Madrid had built a new ground at Chamartín, adjoining the site of today’s Estadio Bernabéu. Of 15,000 capacity and unveiled in 1924 with a friendly against recent FA Cup winners Newcastle, Real’s first proper home had to wait the first three seasons of La Liga before witnessing a title-winning run in 1931-32.

Previously mid-table, they simply bought the best goalkeeper in the land, probably the world, in Ricardo Zamora.

Soon afterwards, to everyone’s dismay in Catalonia, Barcelona legend Josep Samitier defected to the champions – playing under their original name of Madrid FC, as royal insignia had been dropped from football clubs’ crests during the pre-Civil War Second Republic.

Fighting on the side of Franco’s Nationalists during the Civil War, Bernabéu returned to Madrid to find the club he had joined as a boy in complete disarray. Chamartín was a ruin, players and officials dispersed.

Taking over as president in 1943, Bernabéu reconstructed Real. Within a year, he had worked his influential contacts to gain credit to build a new stadium on the Paseo de la Castellana, a prime site surrounded by banks and prestigious institutions. Back then, it was called Avenida del Generalísimo.

It is hard to assess exactly how much Real Madrid were ‘Franco’s team’. It could be argued that by allowing Barcelona fans to express their Catalan sympathies at the Nou Camp every other Sunday and not on the streets, Franco was happy for football to be a popular distraction. FC Barcelona won the title as many times as Real in the immediate post-war period.

What they didn’t have was the European Cup, nor the man whose devastating play across the pitch brought it to them year after year, Alfredo di Stéfano.

Bernabéu had his stadium, the New Chamartín inaugurated in 1947, a whole decade before Barcelona’s Nou Camp. Working with his right-hand man, French speaker and basketball administrator Raimundo Saporta, he also had his tournament.

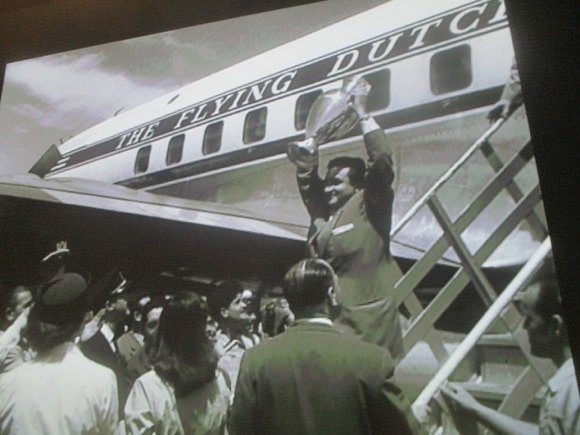

It was Bernabéu and Saporta who planned out the European Cup with journalists from Parisian sports daily L’Équipe and Hungarian manager Gusztáv Sebes. And, with Saporta the savvy negotiator, Bernabéu signed the greatest player of the era, if not the century, Di Stéfano.

Saporta had organised a successful basketball tournament at Real in 1952 to mark the club’s 50th anniversary. Offered a role on the more prestigious sports department, too, Saporta said that he knew nothing about football. “Too many people do,” replied Bernabéu.

Arranging a half-baked proposal to share Di Stéfano with equally keen Barcelona after the first season, Saporta brought the Argentine to Madrid. He knew that the forward’s considerable ego would not allow then Barcelona star László Kubala to share the limelight.

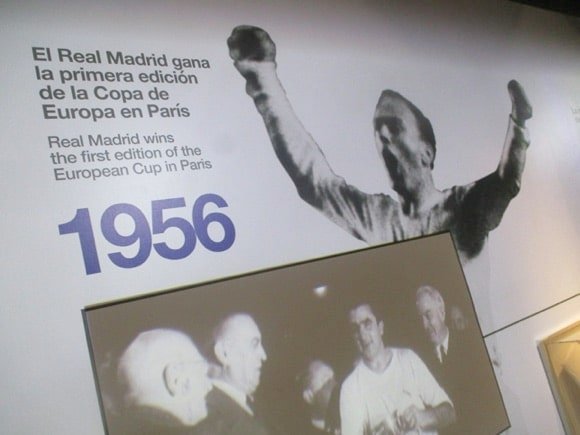

With speedy winger Francisco Gento providing the crosses, and fellow South-American forward Héctor Rial signed upon his recommendation, Di Stéfano lit up the inaugural European Cup in 1955-56.

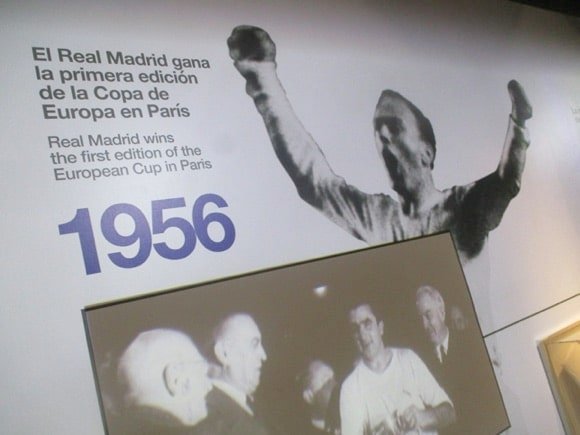

By now, the Stadio Bernabéu had been named after the man who built it, and it welcomed a crowd of just under 130,000 for the semi-final first leg against Milan. In the final against Stade de Reims in Paris, Di Stéfano opened the scoring for Real, Rial hit two, the second the decider in a 4-3 win.

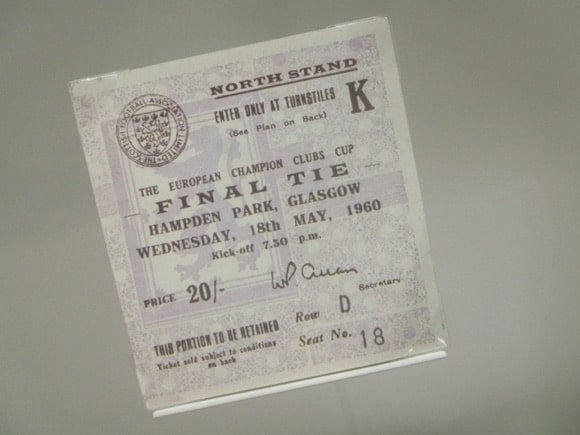

Signing the opposition’s star player, Raymond Kopa, then Hungarian exile Ferenc Puskás, Real Madrid reigned supreme. For the club’s fifth and final European Cup triumph, Puskás and Di Stéfano shared seven goals to give the 127,000 crowd at Hampden Park and 70 million TV viewers a final few ever forgot. Real’s 7-3 win over Eintracht Frankfurt is considered a masterclass in football.

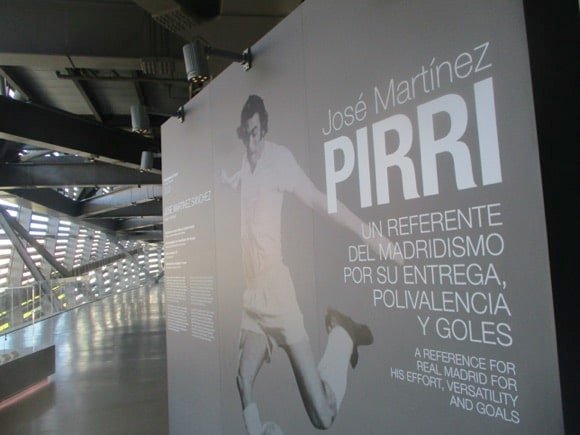

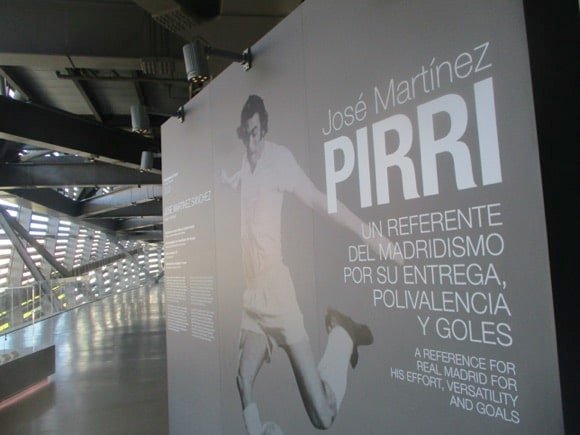

The Magyar got all three in Real’s next final, in 1962, but it wasn’t enough to beat an explosive Benfica side and the era was over. The yé-yé generation of Pirri and Amancio starred in Real’s sixth European Cup win of 1966 – as did Gento, who also appeared in the Cup Winners’ Cup final of 1971, the defeat to Chelsea his ninth European final.

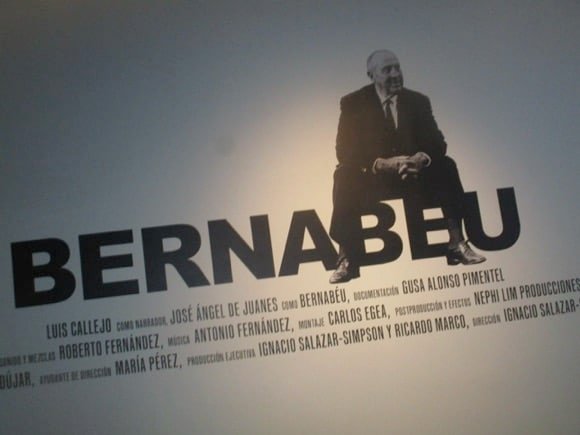

Santiago Bernabéu remained Real president until his death in 1978, having completely transformed the club he doted on. Along with all the silverware and his palatial eponymous stadium – soon to be revamped to host the 1982 World Cup – he had also set up a training complex, the Ciudad Deportiva, for youth and first teams, close to the Estadio Bernabéu.

This was later replaced by the Ciudad Real Madrid, opened in 2005, where the Alfredo Di Stéfano Stadium was unveiled with the visit of Stade de Reims 50 years after the first European Cup final of 1956. Out at Valdebebas towards Barajas Airport, the 6,000-capacity ground was put to good use during the pandemic, even staging a Champions League semi-final with Chelsea in 2021.

As opposed to the star core of the 1950s’ side, the Spanish quintet headed by Emilio Butragueño and Michel 30 years later, winning five straight league titles, were all home-produced, coming through the reserve side, Castilla. Four were Madrileños, although the leading goalscorer was firmly Mexican. A star of the 1986 World Cup like his striking partner Butragueño, Hugo Sánchez would claim four straight Pichichi trophies for being leading league goalscorer.

Castilla, meanwhile, even made an appearance in Europe, having lost the Copa del Rey 6-1 to the senior side in 1980 but overcoming cup specialists Athletic Bilbao on the way. This particularly special reserve team then beat West Ham 3-1 at the Bernabéu, Trevor Brooking, Billy Bonds and all, but failed to progress in the Cup Winners’ Cup after the Hammers hammered them 5-1 after extra-time at Upton Park. Castilla spent two decades in the Segunda without being able to rise any higher.

Back at senior level, European silverware was limited to two consecutive UEFA Cups until the arrival of Fernando Hierro and locally born striker Raúl. With foreigners Roberto Carlos and Pedja Mijatovic, Real’s 32-year title wait for Europe’s premier trophy ended in 1998. This feat was repeated in 2000, with Steve McManaman and young goalkeeper Iker Casillas.

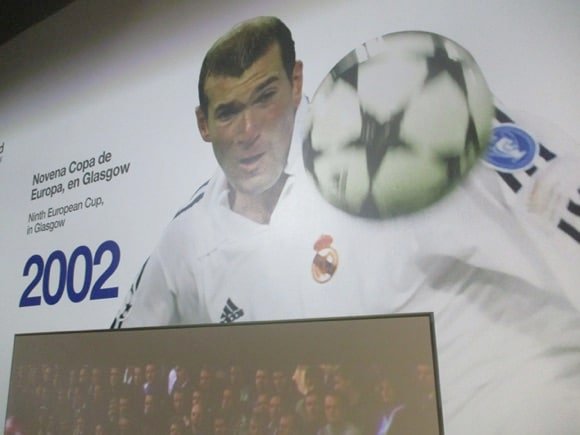

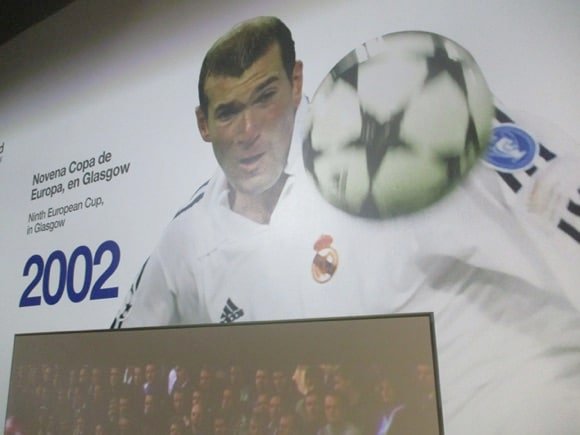

Incoming president Florentino Pérez had built his campaign on the transfer of Figo from Barcelona, the first of the Galácticos – Zidane, Ronaldo, Beckham – who would turn Real into a multi-million euro circus. With it came just one Champions League trophy, in 2002, decided by an outstanding Zidane volley. La Liga became a two-horse race.

The return of Pérez in 2009 saw further astronomical signings, notably Cristiano Ronaldo (€94 million) and Kaká (£60 million). With the arrival of José Mourinho, a real buzz returned to the Bernabéu. Despite the record league victory of 2012 (most points, most goals), and 60 goals from Ronaldo, Real again failed in Europe. Mourinho was replaced by Carlo Ancelotti, a popular choice – and, in 2014, the second coach to win the Champions League three times.

Starved of Europe’s premier crown for 12 years, that night in Lisbon, Ancelotti’s Real lined up against city rivals Atlético. Trailing the recently crowned domestic champions 1-0 in stoppage time, Real equalised thanks to a vital header by stalwart defender Sergio Ramos. Recent €100 million signing Gareth Bale had missed several chances beforehand, but nodded in a second goal in extra-time. Ronaldo then sent the tie and the title beyond reach.

Under former Real star Zinedine Zidane, the Merengues failed to defend their league title, having a first league domestic crown in five years in 2017, brushing aside previously dominant Barcelona.

In 2016, the same Madrid rivals met in Milan, the margins even tighter as the Champions League title went to the Merengues on penalties. In 2017, after a bright start by Juventus, Real simply powered past the Italians on the hour. There was simply too much quality in the side – Luka Modrić, Toni Kroos and Isco would grace any top European team.

While that night was Ronaldo’s, 2018 belonged to Bale. His jaw-dropping bicycle kick to put Real two goals ahead over Liverpool was probably the finest goal ever seen in Europe’s grandstand fixture, rivalled only by his manager’s in a Madrid shirt in 2002.

Ironically, apart from the career-ending blunders of Liverpool keeper Loris Karius, the talk afterwards was of Bale and Ronaldo’s future at the club. Having persuaded Sergio Ramos to stay at the Bernabéu by making him captain in 2015, Pérez failed to keep Ronaldo at the Bernabéu before the 2018-19 campaign.

Until his departure to Juventus, Cristiano Ronaldo had been the poster boy for this era-defining Real side. Epic Clásicos with Barcelona pitted the Portuguese against Lionel Messi, the pair ever in contention for the most prestigious annual player awards.

Zidane was replaced by Julen Lopetegui, the result a near disaster. A 5-1 defeat to Barça left Real in ninth place, and near unprecedented shame. Zidane then returned, ten months and two managerial changes later, to steady the ship.

New €100 million signing Eden Hazard could do little about a 3-0 tonking by Paris Saint-Germain that opened the group stage of the Champions League in 2019-20 – with Ramos, Modrić and Marcelo in their thirties, Real seemed as vulnerable as at any point this century.

But the departure of Ronaldo opened the door for the previously underrated Karim Benzema to shine. Long unbeaten runs in the pandemic-hit league season allowed Real to stay ahead of a crumbling Barça side and claim only their third title since 2008. Benzema hit the brace that confirmed the triumph against Villarreal, home games having been switched to the smaller Alfredo Di Stéfano Stadium at the training complex.

Despite only one defeat in 29 league games, Real failed to defend their title in a tight three-horse race during trophyless 2020-21. Zidane was out the door again, Ancelotti returned, only to oversee a bizarre defeat in the Champions League group stage to Sheriff Tiraspol of Moldova. Few gave Real many chances of the ultimate prize in 2021-22. How wrong they were.

With Modrić shining in an evergreen midfield, Benzema world-class and Brazilian Vinícius Júnior a livewire on the wing, Real surprised many by winning their Champions League group and holding Paris Saint-Germain to a late 1-0 win in France in the first knock-out round.

When Kylian Mbappé scored another at the Bernabéu, PSG held all the cards only for defensive nerves, pinpoint passing from Modrić and a 17-minute hat-trick from an awesome Benzema to turn the tide. It was a stellar European night.

More were to follow. Another hat-trick by Benzema at Stamford Bridge seemed to put the quarter-final beyond Chelsea, until the Blues led Real 3-0 at the Bernabéu. An improving Rodrygo then sent the tie into extra-time, during which Benzema provided the inevitable decider. Modrić, again, belied, his 36 years with pinpoint passing under pressure.

A determined brace by Benzema halted an steamroller of a first-leg performance by Manchester City in the semi-final but the real drama came in the last five minutes of the tie in Madrid. Trailing 0-1, with the final beyond them, Real came back from the dead thanks to two very late goals from Rodrygo.

A Benzema penalty early in extra-time then settled one of the greatest European semis of all time, two sides of superstars playing high-quality, high-wire football to the very death. Expert substitutions by a calm, measured Ancelotti also took Real to the final, French teenage midfielder Eduardo Camavinga coming on so effectively as he had done against Chelsea.

It was ironic that the club’s last-ditch run to the final, overcoming all the odds, had so many neutrals rooting for them, because until then, Real represented the spend-what-may approach to success. It was all last-gasp, seat-of-the-pants stuff, overcoming three stupidly wealthy clubs backed by petrostates and oligarchs, to reach the Paris showdown against Liverpool.

Originally planned to be played in St Petersburg, the game was switched to the French capital despite pressing claims from Budapest. It proved to be a tragic error, shocking scenes around the Stade de France leading to the match being delayed by 36 minutes.

Not only were ticket-holding Liverpool fans being attacked by police for trying to get into a football match, they were set upon in the streets of St-Denis afterwards, with no protection offered.

Miraculous saves by Thibaut Courtois, sterling midfield work by a trio with a combined age of 98, heroic defensive stops and a cunning breakaway goal all helped bring the trophy back to the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu.

Real had already won La Liga at the end of April and had had time to prepare – Liverpool, chasing revenge for 2018, had seen their title slip away in the very last minutes of their league season just days before.

A chequered season in 2022-23, interrupted by the World Cup in Qatar, not only allow Real to regroup, bidding farewell to Bale and, after 15 years, Brazilian left-bank Marcelo, but also bring the €1.1 billion overhaul of the Estadio Bernabéu closer to completion. Proposed shortly after club president Peréz returned in 2009, the project saw costs rise and logistics tangle following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Real had returned to the stadium in September 2021, 18 months after leaving it, pandemic ruiles restricting crowd numbers anyway. The real homecoming came two years later, with a game against Getafe, the Bernabéu debut of €103 million signing Jude Bellingham, whose arrival at Real proved to be spectacular.

Scoring in his first four games, including a typical stoppage-time winner for his introduction to the home crowd, Bellingham equalled Cristiano Ronaldo’s record ten goals in his first ten games set in 2009. His two to silence the Barcelona crowd will live long in the memory, his first from 30 yards worthy of any El Clásico. Almost no other player since Di Stéfano has made such an impact for Real, so quickly, as the 20-year-old Englishman.

But, even without the Saudi-bound Benzema, it was the old hands who also prevailed in the silverware-laden campaign of 2023-24. Toni Kroos was bowing out at the very top of his game, Luka Modrić was enjoying another near-50 game Indian summer of a season and academy graduate Dani Carvajal was clocking up his 12th season raiding the right wing in Real colours.

After a heroic display from unsung Ukrainian keeper Andriy Lunin in a penalty shoot-out to surprise Champions League holders Manchester City, los Merengues saved the real drama for the last seconds of the semi. As Bayern Munich prepared for an all-German showdown with Borussia Dortmund, Germany-born Joselu hit two very, very late goals to reverse the scoreline, send the Bernabéu into ecstasy and Real to Wembley for the final.

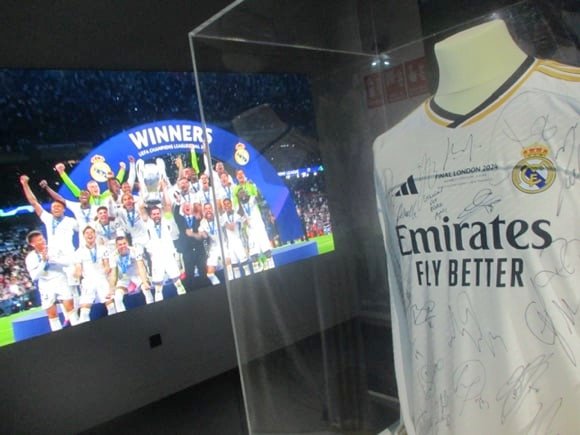

There, in his home country against his former teammates, Bellingham missed a solid chance to put Real ahead before Carvajal opened the scoring with extra-time looming. As Real players celebrated a 15th title, the spotlight fell on Toni Kroos, in his last club game, the league having long been tied up thanks to a defeat-free streak running all the way back to September 2023.

With Kylian Mbappé arriving on a free from PSG, Ancelotti’s men stretched out their unbeaten league record to 13 months and 42 games until a rude awakening by Barcelona in the Bernabéu in October 2024.

Still served by a 39-year-old (!) Modrić, the fab four attackers of Bellingham, Rodrygo, Mbappé and Vinícius Júnior then racked up the goals to top La LIga and but suffered a significant defeat at the hands of Arsenal to end Real’s perceived dominance of the Champions League.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

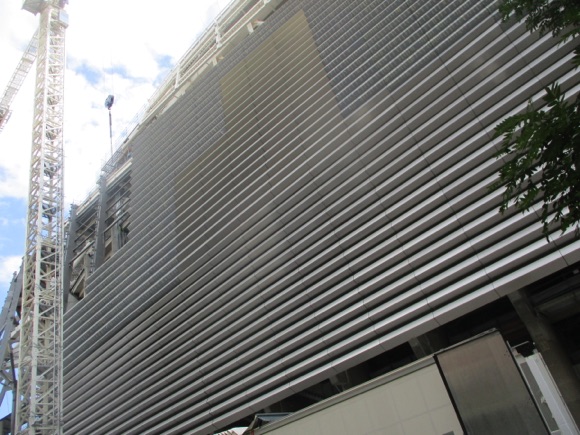

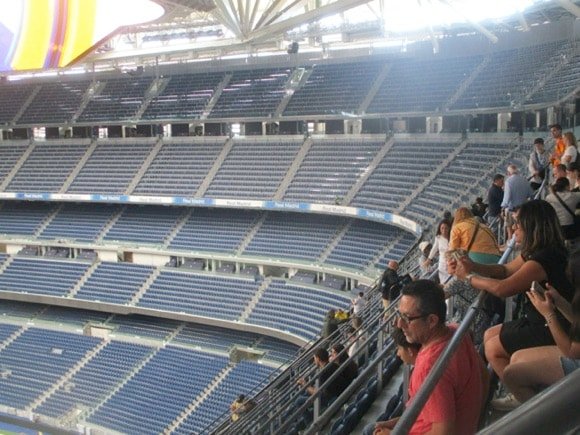

Estadio Bernabéu del Siglo XXI, the project to bring Real Madrid’s Franco-era football temple into the 21st century, has cost €1.17 billion and taken well over four years to complete. While an official unveiling has long been delayed, the main development ran from June 2019, when construction workers first moved in, to September 2023, when new signing Jude Bellingham hit a 95th-minute winner against Getafe.

“I’ve never,” reflected Bellingham, after his fourth game in a Real shirt and the club’s first under the stadium’s retractable roof, “heard a noise that loud on a football field”. It was perhaps no coincidence that the young Englishman had scored in front of the Fondo Sur, where right-wing ultras have been replaced by Real’s younger yet most vociferous fans.

Wrapped in slatted sheets of stainless steel, the arena is not only the perfect stage for yet another golden era for the club, it’s a new one for the Spanish capital. Taylor Swift already had the neighbours complaining about the noise levels during her two shows here in May 2024. which made full use of the 3,700 square metres of LED screens. The 360-degree video board had not long made its debut at El Clásico in April 2024.

Big-name concerts are not only facilitated by a retractable roof but a retractable pitch, removed in sections by a system of hydraulic lifts. While another system airs and irrigates these strips of football turf below ground, an artificial surface can host fairs and fashion shows, basketball and tennis matches.

And that’s without mentioning the 2030 World Cup Final earmarked for the Bernabéu, just under a half-century after Tardelli’s iconic goal celebration when Italy won here in 1982, in front of 90,000 spectators. Given the new sixth tier, the current capacity of 78,297 is 50,000 fewer than were packed into the original stadium in Real Madrid’s pioneering European heyday.

It was Santiago Bernabéu himself who built what was known as the new Chamartín, close to the original stadium of the same name damaged in the Spanish Civil War. It was opened on December 14, 1947, with game against Belenenses, not long crowned Portuguese champions.

The original capacity of 75,000 was expanded to 125,000 in 1954, on the eve of Real’s European Cup hegemony. Renamed Bernabéu by club members shortly afterwards, this wedding-cake arena was the perfect stage for Di Stéfano, Gento and Puskás.

The hosting of the World Cup in 1982 reduced capacity to 90,000, mostly covered by a new roof. Further improvements, and increased seating and safety measures, then lowered this further, to 81,000, including 4,000 VIP seats.

Towers on each corner were then added before the Bernabéu became all-seated in 1997, by which time Real’s ultras had earned a notorious reputation in the Fondo Sur.

When the announcement in 2010 was made of the Bernabéu’s transformation for the 21st century, returning Real president Florentino Pérez had already spent €127 million on a massive upgrade half a decade earlier.

New VIP areas, bars and restaurants had been installed, to increase match-day revenue and elevate the Bernabéu to UEFA elite status, allowing it to host the Champions League final of 2010.

Once the president’s new plan for a complete overhaul was approved in 2011, no sooner had the tender for its design been won by Hamburg-based architects Gerkan, Marg & Partners, than the whole project was put on hold by Madrid’s supreme court in 2015.

Dialling back the initial concept of a built-in shopping centre and hotel – plenty of quality accommodation surrounds this commercial zone of Madrid in any case – Pérez and his board sent the architects back to the drawing board.

The result was approved in 2017 and initiated in 2019, The long construction process then coincided with the pandemic – by chance, Pérez had timed the last home game here to be El Clásico in March 2020, days before lockdown.

For 18 monthe, the team decamped to the Estadio Alfredo Di Stéfano at the club’s training complex in Valdebebas, home of third-tier reserve side Castilla and Real’s women’s team. Of all the echoing stadiums experienced on people’s TV screens, surely the most bizarre was the sight of the world’s greatest superstars battling for glory on a training pitch surrounded by 6,000 covered seats.

Returning to a half-complete Bernabéu in front of crowds of 20,000 in September 2021, Real could play before 60,000 by season’s end, although the Ukrainian War had caused a scarcity of construction materials and prices to rise.

Pretty much operational by September 2023, dovetailing with the dramatic arrival of Jude Bellingham and preceding that of Kylian Mbappé, Bernabéu XXI also heralds a new dawn for Spanish football, half a decade ahead of the 2030 World Cup. Barcelona’s new Nou Camp is scheduled to open in 2025, Athletic Bilbao have long waved goodbye to their old San Mamés and Real Sociedad’s Reale Arena gained its new look in 2019.

The enormity of the undertaking at the Bernabéu can best be appreciated by taking the stadium tour, the bird’s eye view from the fifth level two below the new Skywalk and Skybar, and one down from the tier set aside to away fans, high above the Fondo Norte in sector 631. Access at the corner of Calle de Rafael Salgado/Padre Damián.

While visiting supporters in Spain tend to travel in the low hundreds, for major European games, such as the one with Manchester City in February 2025, an allocation of nearly 4,000 seats is spread over this north-east corner of the stadium. It’s as far away as possible from the loudest Real faithful in the lower rings of the Fondo Sur.

The home end is set by Avenida de Concha Espina, whose sidestreets are the main bar hub. Backing onto the main boulevard, Paseo de la Castellana, the Lateral Oeste houses the prime seats in Preferencia, while the Lateral Este along the opposite long sideline runs along Calle de Padre Damián.

Each of the four stands has six levels, correlating with the three-digit number on each ticket, 1xx closest to the pitch, 6xx the highest up.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

The stadium has its own metro stop, Santiago Bernabéu, on dark-blue line 10, metro entrances on Paseo de la Castellana itself, right next to the stadium. The line passes through central Alonso Martínez and Nuevos Ministerios, linking with pink line 8 for the airport.

In line with the overhaul of the stadium, the metro station will also be completely revamped by 2027, trebled in size, and provided with 12 new lifts and 24 escalators. Decoration will reflect the history of the Bernabéu and the area around it.

If you’re heading to Ciudad Real Madrid and the Alfredo Di Stéfano Stadium, you need Valdebebas station almost next door. From main Atocha station, take regular local train C1 or C10 on the cercanía network, journey time 25mins, via Nuevos Ministerios.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Purchasing a Madridista Premium card (€35/year, €20 junior/year, +€1 for the card) allows you ticket priority around a week before any game. Admission then goes on sale to the general public about five days in advance.

The cheapest tickets you’ll find start at around €75. For high-profile domestic and European fixtures, it’s €125.

There are also hospitality packages from €325, more than twice as much for high-profile fixtures.

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

Real’s Bernabéu store (daily 10am-8.30pm) is located at Gate 30 on Avenida de Concha Espina, two floors and 700 square metres of Merengue merch.

There’s a chic, contemporary branch at Gran Vía 31, a smaller one at Calle Arenal 6 and a long-established one at Calle del Carmen 3 (all daily 11am-8pm), all within a short walk of Sol.

The iteration of the hallowed home shirt for 2024-25 features adidas shoulder stripes and that regal badge. Away choice is orange, third charcoal with a fold-over collar.

Of the T-shirts, the one showing all 15 locations for Real’s European Cup/Champions League triumphs, done out like an underground map, might have passers-by guessing.

The retro collection harks back to the Raúl era of 1999-2000, home and away shirts as well as tracksuit tops. Gifts include team-bus jigsaw puzzles, mini Bernabéu models with real grass and a cutting from the goal net at the stadium used for the Champions League campaign of 2021-22.

tours & Museum

Explore the club inside and out

The Classic Bernabéu tour (€35, 5-14s €29, in person +€3; daily 9am-6.30pm, match nights up to 5hrs 30mins before kick-off) involves a gradual ascension of the new stadium by a series of escalators to the impressive club museum and viewing platform overlooking the pitch from sectors 501-503.

Visually striking, presented in English and Spanish, the museum runs through the club’s history in chronological order, with a short biopic of Santiago Bernabéu outlining just how much the old grandee transformed the club, helping to create the European Cup at the same time.

This is also one of the few trophy rooms with a serious wow factor – 15 European Cups/Champions League trophies, as many as Barcelona, Manchester United and Bayern Munich put together.

Note that tours are still affected by construction works, and some stairs are involved.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

Outlets built into the Bernabéu have all affected by the stadium construction. Chain eatery Tony Roma’s has moved to the other side of Concha Espina, where it faces competition from refined Italian restaurants Alduccio and Ôven along the same stretch. Still in place on Concha Espina, La Barra nods at being a beer hall while Alright Birrä has transformed from nightspot to sleek diner with TV football.

The narrow streets leading off Concha Espina are lined with bars. On San Juan de la Salle, El Refugio caters to the rock fraternity, evenings only Thursdays through Saturdays. Alongside and by far the best option is Aki Madrid, a friendly rock bar with a slightly alternative feel, fair prices and seats outside.

Across on C/Marcellano Santa María, little Bar La Saeta displays framed photos of the Saeta Rubia, the Blond Arrow, Di Stéfano. Similarly old-school, La Vienesa has worn well with age, serving cheap drinks and tapas amid Real Madrid scarves and archive photos for 60 years or more.

Also on C/Marcellano Santa María, chic restaurant Mar de Copas and Iciar, a former quality Real bar, El 7 Blanco, show the gentrification taking place now that the new Bernabéu is ready. Over the road, La Fontanería, Carmelie and La Ysabela deal with match-day overflow by serving standard drinks and tapas.

Quintá attracts pre-match Real fans, its name related to the Butragueño era. Trendier El Retoque provides a convivial terrace by day but be prepared to pay top dollar for platos, tapas and your beer or wine. Further down, La Pelaya fashions itself as a contemporary beer hall, amid bare brick. In between,

Still holding out as a beacon of authenticity, with a beer terrace, Casa Puebla (‘Since 1899’) is a tiled Castilian classic in thrall to bullfighting and Los Merengues.

Across the street, although Taberna La Daniela looks the part, it’s one of a citywide chain of pricy Madrileño restaurants.

On the next street over, c/de Santo Domingo de Silas, you’ll find pre-match eats at chain burger bar with TV football, Carl’s Jr, and traditional Asturian seafood, La Chalana.

On the opposite side of the stadium on Rafael Salgado, Basque restaurant José Luis is of similar vintage, close to La Bodega, a corner bar smartened up as part of a revamp but not a bad pre-match beer choice. Alongside, Volapié is a chain taberna – there are three along Paseo de la Castellana alone.

On C/del Padre Damián, No Cabe Duda is an upscale tapas place with its TV tuned into football, while further up, Cervercería La Terca may feel equally antiseptic but has at least invested in a job lot of classic archive photos of great Real moments to decorate the place.

In the same vicinity, and a great pre- and post-match choice, Limbo brightens c/de Manuel de Falla with its colourful terrace furniture and lends an alternative feel to an otherwise staid locality. There are quality eats, too, thanks to a capable open kitchen overseen by grill master Javier Brichetto, accompanied by tap beers El Águlla and Paulaner, or craft Bastarda.

At the stadium itself, Puerta 57 by the club shop has reopened for champagne and olives, or beer in a chilled glass, after stadium tours, otherwise it’s VIP-only on match nights. If you’re taking the stadium tour, there’s a little snack outlet by the vertiginous viewing point, booze-free, while at the south-east corner of the Bernabéu, where Padre Damián meets Concha Espina, shiny Plaza Mahou is now in full swing, serving the namesake Madrileño cerveza along with classic tapas.