A fan’s guide – the club from early doors to today

Juventus, ‘La Vecchia Signora’, attract seven million supporters the length and breadth of Italy. For other 50 million Italians, ‘the Old Lady’ is a shameless hussy, buying her way to success – as demonstrated by the match-fixing scandal exposed in 2006, which saw Juve relegated for the first time.

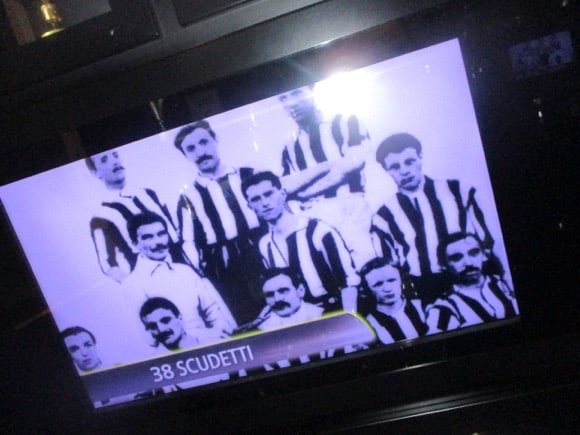

Juve then went on to dominate the Italian game, just as they had done during long periods of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. The most recent monopoly reaped nine straight titles between 2012 and 2020.

But Italy’s most decorated club has still only won Europe’s premier trophy twice, the first the tainted final of 1985. Those nine Scudettos were interspersed with appearances at two Champions League finals, and defeats to superior Spanish sides in 2015 and 2017.

At least Juventus can point to the ongoing success of their self-owned arena, an example-setting rarity in Italy where ageing state-run stadia are the norm. It’s not only the 41,500-capacity Allianz Stadium, though. Being built around it is the J-Village of a training centre, head office and hotel. Italian football has at last joined the 21st century.

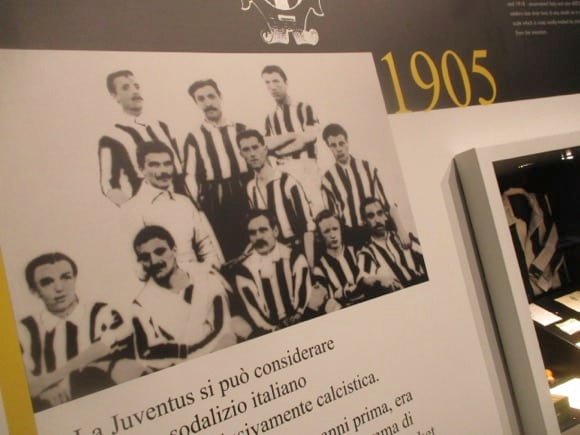

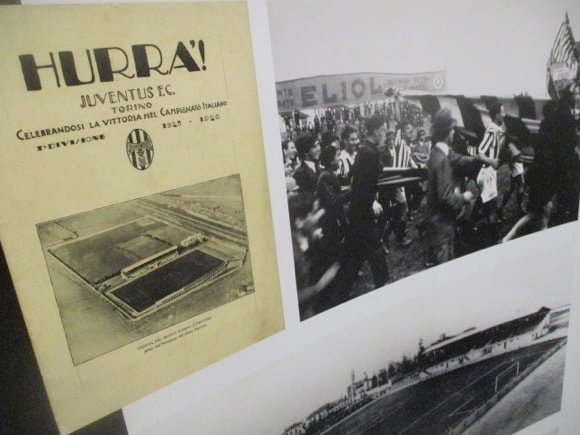

Juventus were founded in 1897 by pupils of Massimo d’Azeglio grammar school. The bench they met on stands at the club HQ on piazza Crimea. In 1906, some members formed a breakaway club, Torino, thus setting up one of Italy’s most enduring city rivalries, il Derby della Mole.

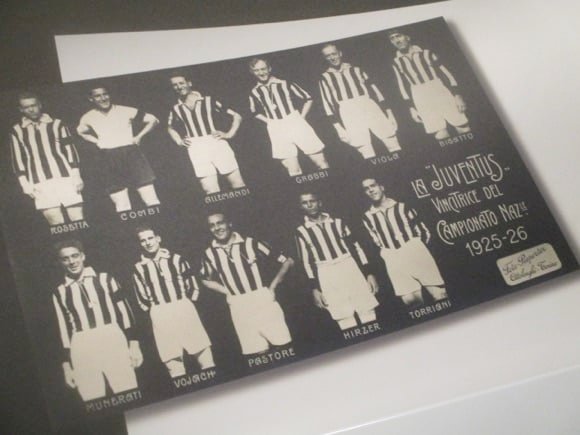

The Agnellis of Fiat fame took over Juve in 1923, and bought top talent to win five consecutive titles a decade later. World Cup winners Raimundo Orsi, Luisito Monti and Giampiero Combi wore Juve’s black-and-white stripes – shirts originating from Notts County.

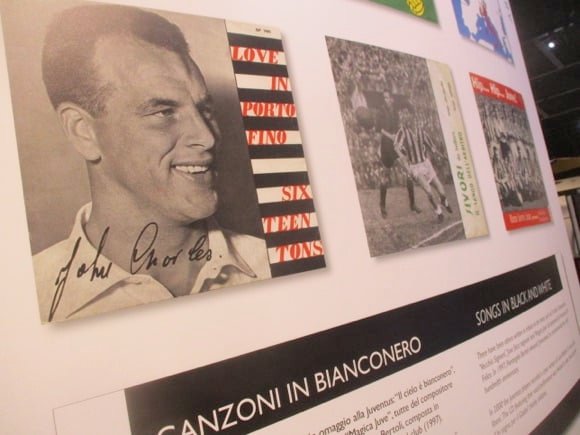

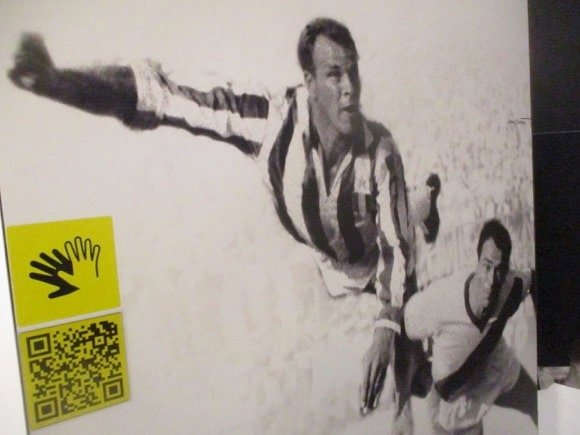

Welshman John Charles and Brazilian Omar Sivori starred in the post-war period but the classic Juve era came in the late 1970s and 1980s. Under Giovanni Trapattoni (‘Il Trap’), forward Roberto Bettega and goalkeeper Dino Zoff made Juve near unbeatable at home, before foreign stars Liam Brady, Zbigniew Boniek and, most importantly, Michel Platini, pushed Juve to another level.

Despite Platini’s imperial presence – top league scorer from midfield three seasons running – Juventus were never fully acknowledged masters of Europe, winning an irrelevant final against Liverpool in the chaos of Heysel 1985.

The 1990s began with the opening of the soulless Stadio delle Alpi – created with security in mind, given the 39 deaths of Juve fans at Heysel – and continued with the arrival of coach Marcello Lippi. Juve made three Champions League finals, winning one, and took three titles. Helping to Juve to success were Zinedine Zidane and Alessandro Del Piero, a prodigious talent from Padova.

Guided by Pavel Nedvěd in midfield and backed by Gianluigi Buffon in goal, the Zebras won back-to-back titles but lost the Champions League final of 2003 to Milan. Two further titles, under Fabio Capello, were struck from the records after the match-fixing scandal of 2006.

At the same time, the club was planning an entirely new stadium on the site of the dreaded Stadio delle Alpi. Demoted to Serie B and bereft of departing foreign stars, Juve must have questioned the wisdom of laying out €155 million, €60 million of it in loans. Opened in 2011, the Juventus (aka Allianz) Stadium has since proved to be a superb investment, and a shining example to the club’s peers.

Based at Torino’s Stadio Olimpico in the interim, Juve only needed one season to end their enforced sojourn in Serie B, talismanic Del Piero, Nedvěd and Buffon sticking by the Old Lady to play their way out of ignominy.

With Antonio Conte at the helm, Del Piero captain and Andrea Pirlo pulling the strings, Juve went the entire 2011-12 season unbeaten and picked up a first league title in nearly a decade. It was also an emotional farewell for Del Piero, who bowed out after a record 705 appearances. Clean sheets by Buffon then helped Conte’s Juve to retain the title in 2013.

With Carlos Tevez taking Del Piero’s No.10 shirt, and Pirlo as peerless as ever, Juve walked to a third consecutive title in 2014. Sadly, they missed out on winning European silverware at home, losing to Benfica in the semi-final of the Europa League, the final being played in Turin.

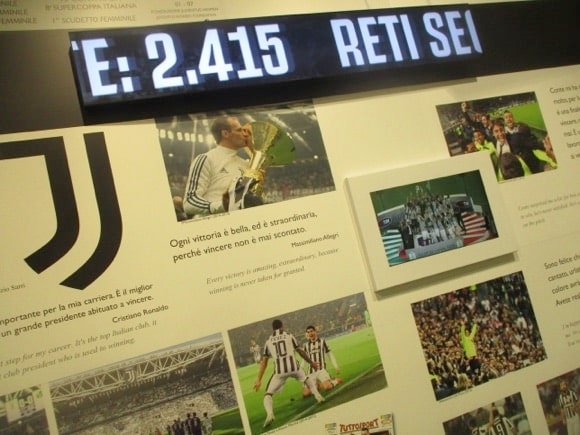

Conte having taken the national job, Massimiliano Allegri proved to be a savvy coaching appointment despite initial scepticism. A domestic double was outshone by an impressive win over Real Madrid in the semi-final of the Champions League in 2015. In the showdown in Berlin, Juve recovered from an early goal by Barcelona to draw level, but didn’t quite have enough in the final third.

Off the pitch, Allegri tempered the losses of Paul Pogba and Spanish striker Álvaro Morata with the wise buys of Gonzalo Higuaín for €90 from Napoli and Miralem Pjanić for €32 from Roma, top of the Serie A goalscoring and assist charts respectively in 2015-16.

In 2017, after a record third domestic double, Juve initially gave a good account of themselves in another Champions League final. Having stomped Barcelona 3-0 in the quarters, the Zebras looked set to break the Spanish stranglehold on Europe’s premier trophy. A wonder goal from Mario Mandžukić levelled the scoring against Real Madrid in the Cardiff final but poor discipline saw the Turin side collapse on the hour. The 4-1 defeat is one Gianluigi Buffon will not forget in a hurry.

Argentine international Paulo Dybala started the 2017-18 campaign with hat-trick after brace after hat-trick, although for much of the campaign, a seventh straight Scudetto was far from assured. In the end, Juve edged the league above Napoli.

Clearly superior to everyone else in Italy, and equally clearly inferior to the Spanish giants at the very highest level, Juve went for broke in 2018. The club paid Real Madrid €100 million for Portuguese superstar Cristiano Ronaldo. It was a record fee for a player in his thirties, the five-time winner of the Champions League then aged 33.

The transfer proved to be a mixed blessing. Still dominant at home, an ageing Juve were no match for the youngsters of Ajax in 2019 and lively Lyon in 2020, Champions League dreams ended each time in the earlier knock-out rounds.

Ceding their title to Inter in 2021, Juve ended 2021-22 without a trophy of any kind, the first drought for over ten years. Not even the return of Max Allegri, the coach behind five of those nine Scudettos, could lift Juventus above fourth place.

Champions League football was still pretty much a given – though nothing better demonstrated the gulf in class on the European stage than the 4-0 defeat by Chelsea in the group stage in November 2021.

The purchase of prolific young Serbian striker Dušan Vlahović from bitter rivals Fiorentina pushed Juve nearer to the Scudetto in 2022-23, but further financial shenanigans at boardroom level led to a points deduction and a European ban the following season.

Clearly superior to everyone else in Italy, and equally clearly inferior to the Spanish giants at the very highest level, Juve went for broke in 2018. The club paid Real Madrid €100 million for Portuguese superstar Cristiano Ronaldo. It was a record fee for a player in his thirties, the five-time winner of the Champions League then aged 33.

Perhaps it was just as well – abject failure in the Champions League meant that Juve only qualified for the Europa League thanks to more goals scored in games with Maccabi Haifa. Their subsequent run in Europe’s lesser competition was not without credit, however, and only an extra-time goal from tournament experts Sevilla prevented Allegri’s men from reaching the final against Roma.

Able to focus purely on domestic matters, Juventus put together a 17-game run without defeat through the autumn and winter of 2023-24, Vlahović once more on target, but a string of draws in the spring fuelled the anti-Allegri lobby in the corridors of power, the faithful servant sacked after winning the Coppa Italia for his furious outbursts just as the trophy was being paraded around the Stadio Olimpico.

The man who had won the club five cups and five league titles had already been shown the red card in the dying seconds of the game – his behaviour (and perceived defensive tactics) cost him his job. HIs replacement, former PSG star Thiago Motta, had transformed Bologna over the two previous seasons.

His former charges all but broke Juve’s unbeaten league record going into December 2024, but Juve remained on course for a European place at least.

Stadium Guide

The field of dreams – and the story behind it

Fashioned out of the unloved Stadio delle Alpi, the Allianz Stadium (aka the Juventus Stadium) was unveiled in 2011 with a friendly against Notts County, the inspiration behind the black-and-white shirts a century ago.

Strikingly modern with flashes of red and green, its contemporary exterior juxtaposes with the stark beauty of the Alps in the immediate background. Holding 41,500 spectators, this intimate venue is the perfect solution to the club’s long-term stadium woes.

In 2003, Juventus took the unprecedented step of buying the stadium for €25 million from the council and developed Italy’s first club-owned, football-focused arena. Giving priority to environmentally friendly methods – the stadium generates heat through solar panels and irrigates its pitch by reusing rainwater – the club were able to build a new arena from scratch for a relatively modest €155 million. It later staged the Europa League final in 2014.

The adjoining J Village has been built up since, and now contains a four-star hotel, the club’s HQ, training centre and media offices, as well as an international business school. Within the stadium complex and long in place are the Area12 mall containing a Juventus megastore, and the Juventus Museum.

The compact stadium comprises the home Tribuna Sud on corso Grosseto and Tribuna Nord on via Druento, behind each goal, Tribuna Ovest and Est Centrale on strada Comunale di Altessano by the Area12 mall contain the best seats along the sidelines. Visitors are allocated sector 110 in the north-east corner between the Nord and Est stands accessed by via Druento near the car park and match-day tram terminus.

getting here

Going to the stadium – tips and timings

The Juventus Stadium is way north-west of town. The quickest way to the ground is to take tram 9 from Porta Nuova station via Bernini to the terminus at Stampalia Cap. From there, you’re a 10min walk away along via Druento. It’s 20 stops between the station and the stadium area, allow 30mins. Trams run every 15mins.

On match days, a special tram 9 service runs from Bernini, on the same metro line as Porta Nuova and Porta Susa, right to the stadium – though this may not be a wise choice for visiting supporters.

On non-match days, if you’re at Rossini, near the Mole Antonelliana, tram 3 goes to Sansovino about 10min walk from the stadium, journey time 20-25mins. Trams run every 12mins.

The closest bus stops to the stadium are Stadio and Druento, on line 72, setting off from Bertola Cap near Castello in town. It’s less frequent, every 25-30mins, and takes at least 30mins from town, possibly 45mins in rush hour.

getting in

Buying tickets – when, where, how and how much

Tickets are only distributed online through the Juventus Official Ticket Shop, for which you need to register, unless you have club membership or a Juventus Card (€15). If you’re making a weekend of it, you can always opt for a match package at the J hotel in the J Village alongside.

Club members can also purchase tickets a week ahead of general sale. Basic stadium membership costs €45/season, €39 11-13s.

For all enquiries, use the contact form on the club website or call +39 011 45 30 486 (Mon-Fri 9am-8pm, Sat 9am-3pm, not hols).

For an average Serie A fixture, you pay €35 (€20 under-16s) for a seat in home Tribuna Sud, or Tribuna Nord, €65 (€35) for a better seat in the Tribuna Nord, while prices in the sideline Tribuna Est or Ovest range from €75-€120 (€40-€60).

what to buy

Shirts, kits, merchandise and gifts

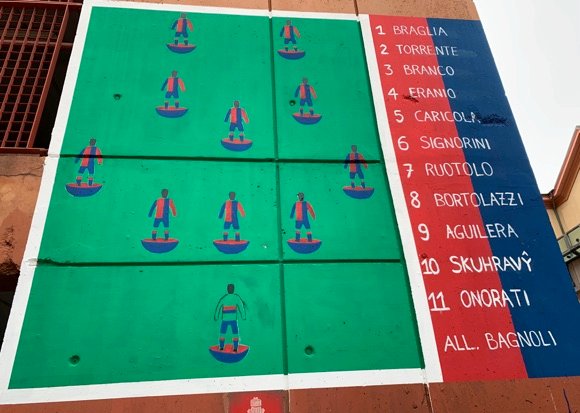

The main Juventus Store (daily 10.30am-7pm) is by the club museum and Area12 shopping centre, behind the Tribune Est where via Druento meets strada Altessano. It’s the largest of its kind in Italy, with shirt-printing, a table-football table and retro shirts galore, from the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s. Scarves and hats carry the all-pervasive J-letter logo. Juventus Subbuteo is a must-have, though Connect 4 sets may be stretching the brand somewhat.

The home shirt for 2024-25 features two thick black stripes either side of interspersing white, the same pattern repeated over the shoulders, but the sleeves white and round-neck collar black, with a thin band of white down the sides.

Away is a lightish yellow with white patterns, offset by a blue collar and shoulder stripes, and touches of pinkish red. Third-choice is a France-like navy, with wing collars fringed by light blue, and the bull of Turin prominent on the chest. Very suitable for casual wear though perhaps not for a muddy tussle in Udine.

In town, there are furry zebras a-plenty at the Juve store (daily 10.30am-7pm) on the corner of Garibaldi and XX Settembre by the Garibaldi stop on the 4 tram line.

On match days, you’ll find many points of sale around the ground, open from 2hrs before kick-off.

Museum & tours

Explore the club inside and out

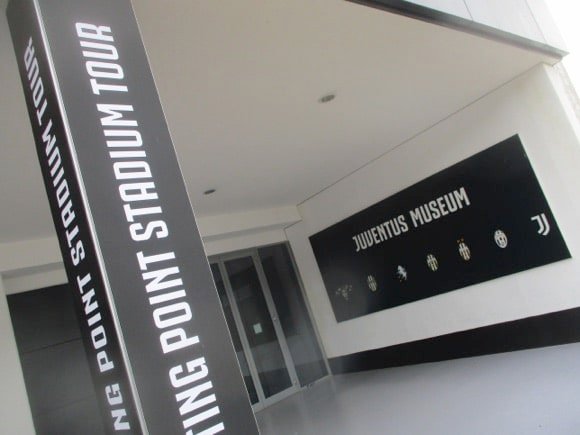

Behind the Tribuna Est, the Juventus Museum (Mon-Fri 10.30am-6pm, 7pm n summer, Thur-Sun & hols 10.30am-7.30pm, match days from 9/9.30am, eve kick-off from 10.3oam) costs €15, €12 or under-16s/over-65s, free for under-6s.

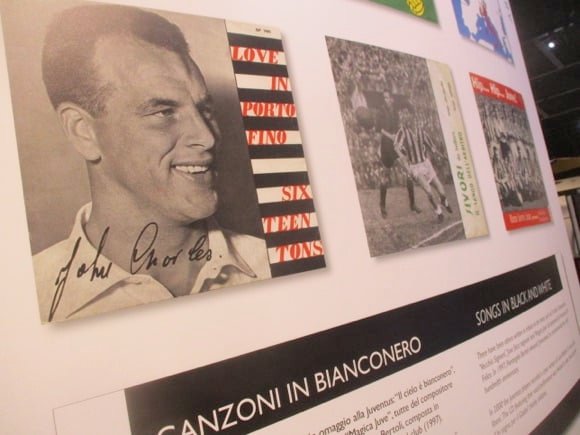

It’s well worth the admission, the visitor taken on a chronological journey through the club’s history, from the mythical park bench to the first titles, then John Charles and the European era. The story is told by way of films, vintage shirts, newspaper clippings, action photos, line-ups and huge imaginative display boards in English and Italian.

There are trophies galore, of course, an immersive, sensurround presentation of Juventus in an emotional mini-documentary, and a video wall of multiple screens showing memorable moments focusing on Juve players – that Tardelli celebration never, ever gets old. Among the familiar zebra-striped paraphernalia are a few curios, such as the record John Charles made at the height of his popularity, Love in Porto Fino and a cover of Sixteen Tons.

Stadium tours (from 10am/11am most days) run several times a day and can only be purchased as part of a combined museum ticket (€29/€24 reduced). Like the museum, they are facilitated by audio guides in five European languages.

Note that although the museum is step-free, the stadium tour is not recommended for those with mobility difficulties.

Where to Drink

Pre-match beers for fans and casual visitors

A few old spots around the crossroads of strada Comunale di Altessano and via Sansovino are frequented pre-match, despite the lure of bland, family-friendly establishments in the immediate vicinity of the stadium and Area12 mall.

L’Elite features photos of the stadium being built, Bar Sport has a terrace, while the Ristorante delle Alpi on via Segantini, just off Altessano, is tradition itself, a 15-minute walk from the ground.

Further up nearer the stadium at strada Altessano 146, Alby and neighbouring Millegusti are standard choices, the former with Forst beer and cheapish meal deals in the basement restaurant.

On the corner with via Druento, Linopassamilvino should serve you the best meal near the stadium, grilled meats a speciality. Draught beer is rarely found Peroni Crudo and the even rarer Meantime IPA from Greenwich.

Round the corner on via Druento, the previously lively pre-match Stadium pizzeria is now the standard Il Pasticcio (No.135), with a TV on the back wall of a featureless restaurant.

Those staying enjoying a match-package stay at the J hotel can take advantage of the Tàola lounge bar for a pre- or post-match apéritif, open to non-guests, too. It’s a fair ten-minute walk to the stadium, so keep an eye on your watch as you sip your Aperol spritz.

Right by the Juventus Stadium, facing the Area12 mall, you’ll find franchise eateries such as the Viennese-themed Wiener Haus, with a decent choice of Central European beers may complement your Schnitzel. Screens beam football amid the faux twee decor.

Around the stadium concourse, many prefer to mingle amid the stalls and stands, tucking into carnivorous delights and sinking a beer or two.