A complete guide to the game across the country

The recent renaissance of Scottish football has been a long time coming. The national side emphatically qualified for the World Cup in 2026, while their valiant efforts at Euro 2020 brought back memories of heroic fixtures and failures of half a century before.

During that pandemic summer, at Scotland’s national stadium, Hampden Park, and at Wembley, Steve Clarke’s men gave a nation reason to cheer. No, it wasn’t the Wembley of ’67, when a world-class Scotland side featuring Jim Baxter, Denis Law and several of Celtic’s soon-to-be European Cup winners overcame almost the exact same England team who had won the World Cup the previous year – but the 0-0 draw of 2021 elicited similar emotions and chaotic scenes in central London.

That same spring of ’67, Rangers also reached a European final, settled by a goal in extra-time. In 2022, Celtic’s bitter rivals took the Europa League final to extra-time and, fatally, penalties. An estimated 100,000 fans had followed the Gers to Seville and, despite the heat and defeat to Eintracht Frankfurt, relatively little trouble broke out.

This for a club that was dead and buried a decade before. A slow, humiliating climb back from insolvency allowed Celtic to dominate the Scottish Premiership (SPL) until Rangers’ raucous and well-deserved title win under Steven Gerrard in 2021.

With Hearts gaining the ascendancy for much of 2025-26, the Scottish game has its keenly awaited counterpoint to the Old Firm rivalry.

Glasgow, home of Hampden, the Scottish FA and Football Museum, has long dominated domestic football. Up until 2025, the title has gone to Glasgow 111 times, 112 if you include Motherwell. The rest have claimed it 17 times, 18 if Motherwell is separate, all since 1890-91.

Many neutrals and outsiders have long hoped that Aberdeen (last title 1985), Dundee United (last title 1983), Hearts (last title 1960) or Hibernian (last title 1952) could present themselves as credible challengers to the Glasgow duopoly. Even in terms of stadiums, those four title winners from long ago play in grounds of 14,000-20,000 capacity. Rangers’ Ibrox holds and invariably attracts 50,000, Celtic Park 60,000.

Scottish teams outside Glasgow depend on fixtures with the Big Two for gate revenue. Would they survive otherwise? Scottish football is remarkable from several aspects, not the least of which is passionate support.

The other is longevity. A four-division professional league – the Scottish Premiership, Championship, Leagues One and Two – consists of clubs formed in the late 1800s whose colours and colourful nicknames have barely changed since. With the occasional new-build exception, many grounds date back well over a century.

Predecessor of the SPFL, the Scottish Football League dates back to 1890, two years after its counterpart south of the border. In fact, it was the mass exodus of top Scots players for professional riches that prompted the main clubs to form the SFL, minus amateur stalwarts Queen’s Park.

Most of the Preston team who won that inaugural Football League in 1888 were Scots, as was the case for Sunderland’s three-time title winners of the early 1890s. Every single Liverpool player in the club’s very first game in 1892 came from Scotland. Why?

Simply put, the Scots invented football because the Scots invented passing. The Scotland team, made up entirely of Queen’s Park players, who faced England in the world’s first international in 1872, had practised in pairs and lined up in 2-2-6 formation. The game in Partick ended goalless. The Scots soon went on to beat England 7-2 and 5-1 and rarely lost a competitive fixture until the early 1900s.

The European successes of the 1960s continued into the 1980s when both Aberdeen and Dundee United won silverware. All major English clubs of the era – Leeds, Liverpool, Derby, Nottingham Forest, Manchester United – featured a core of key Scottish players. The demise of the myriad youth teams at every level in Scotland ended the constant flow of talent south to the very highest level.

While the current non-league game in Scotland, referred to as junior football, remains strong – Auchinleck Talbot have surprised many a top name in the Scottish Cup – direct promotion to the Scottish League from the fifth-tier Lowland and Highland Leagues has been a great success since its introduction in 2015.

Both Inverness Caledonian and Ross County had already given an excellent account of themselves after leaving the Highland League in 1994, and both are now regular competitors in the Scottish Premiership. While the relative success of East Kilbride, Cove Rangers and Kelty Hearts contrasts with the patchier performances of Edinburgh City and Bonnyrigg Rose upon joining The 42, few question the wisdom of the restructure.

Scottish domestic football remains affordable, easily accessible, down-to-earth and downright friendly. Meanwhile, long-term TV and sponsorship deals signed in 2021 have provided a modicum of stability for the 42 member clubs who own the SPFL.

With domestic football on a firmer footing, Scotland’s dramatic qualification for the World Cup in 2026 now allows the Tartan Army to travel beyond the UK for a major finals for the first time this century.

STATION TO STADIUM

Arriving and getting around by public transport

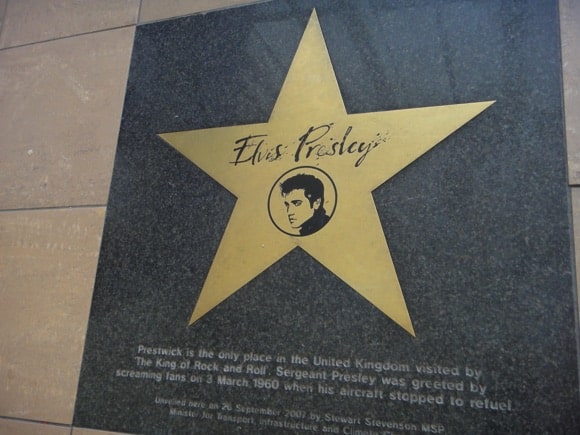

Scotland’s main airports at Edinburgh, Glasgow, Glasgow Prestwick, Aberdeen and Inverness are served by one or both of the major budgets, easyJet, Ryanair and Jet2 (jet2.com). British Airways also flies to most from mainly London bases.

Affordable ScotRail trains cover much of the country. An off-peak day return between Glasgow and Edinburgh is £14. You can also plan your journey with Traveline Scotland, which helps with the myriad private bus companies. These operate both within and between main cities. Glasgow also has its own underground, the Clockwork Orange, while Edinburgh has swift, efficient trams.

Scotland has no motorway or bridge tolls.

TABLES & TROPHIES

The league system, promotion, relegation and cups

The Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL) consists of four divisions – Premiership, Championship, Leagues One and Two – with promotion and relegation between them, as well as play-offs. The 12 teams of the top tier play each other three times, home-away-home or away, before the league splits in two for one more round of fixtures. Each team therefore plays 38 games.

The league winners go straight to the Champions League group stage, the runners-up, thanks to Russia’s suspension, to the third qualifying round. The team in third enters the Europa League play-off round, fourth, the Europa Conference third qualifying round, fifth, its second qualifying round – assuming the winners of the Scottish Cup come from the top four, which is usually the case.

The bottom club drops straight down to the ten-team Championship. The team finishing 11th meets the winners of the Premiership play-offs home and away over two legs.

In the three other divisions, the ten teams face each other home and away twice, for 36 fixtures every season. The play-offs involve a quarter-final between teams finishing third and fourth, the winners facing the league runners-up, then the semi-final winners taking on the one-from-bottom team of the division above, all over two legs.

The club finishing bottom of League Two, ie propping up the whole 42-team SPFL, must play off to stay in the professional ranks. Immediately below the SPFL are two semi-pro regional divisions, each with 18 teams, the Lowland League in the south and the Highland League in the north, with its long tradition dating back to 1893. Within both, teams play each other home and away. The champions of each meet for the two-leg Pyramid play-off, the winners facing the bottom club in League Two, again over two legs.

The bottom clubs of the Highland and Lowland Leagues go straight down to the sixth tier, which is the realm of junior football, considered non-league in England. Despite the shining examples of former semi-pro Cove Rangers and Kelty Hearts in the professional game, many clubs are happy to stay at junior level, without the risk and expense of needing more staff and finding salaries.

Therefore, although the winners of the six leagues within the sixth tier – the Midlands Football League, North Caledonian Football League and North Superleague linked with the Highland League, the East, South and West of Scotland Leagues linked with the Lowland League – can play off for the chance at facing their respective counterpart who finished 18th in the fifth tier, some choose not to do so. Were they to go up, others don’t have suitable facilities to stage semi-pro football, nor the wherewithal to modernise them.

The pyramid system, successful in England where it has long been in place, is new here. At this level north of the border, clubs tend to represent very modest communities with small catchment areas, and operate on a shoestring. Most of the grounds hosting games in the North Caledonian Football League in 2022-23 are of 1,000 capacity or under.

The sixth-tier divisions comprise around 14-16 clubs, although it varies. In the Lowland zone, the East and West of Scotland Leagues stretch to three or four divisions.

At these lowest levels, only SFA members may qualify for the Scottish Cup, the second oldest of its kind and the one with the oldest trophy. For the inaugural tournament in 1874, Queens Park captain James J Thomson, who also took part in the first international match two years earlier, lifted the very same cup as Graeme Shinnie did for Aberdeen in May 2025. The trophy is then returned to the Scottish Football Museum for 364 days a year, and the winning club is presented with a replica.

All clubs in the SPFL, Highland and Lowland Leagues, qualify automatically, as do SFA members in the six sixth-tier divisions. The winners of these six junior leagues may also enter, even if they are not SFA members. The winners of the Scottish Amateur Cup may apply, as well as the holders of the revered and long-standing Scottish Junior Cup, which is how frequent winners Auchinleck Talbot qualified for later rounds until the club’s move out of the junior game. In 2024-25, a total of 130 clubs competed in the Scottish Cup.

The draw is random, no seeding. Replays are played up to the Fourth Round, the tie decided on penalties after the second game. After the Fourth Round, extra-time is played after a drawn game, then spot-kicks taken, with no replays.

The preliminary round in August involves clubs below the fifth tier. Highland and Lowland League teams enter at the First Round stage, League Two sides the Second Round, League One and Championship the Third Round and Premiership clubs the Fourth Round.

Both one-game semi-finals and final take place at a neutral ground, invariably Hampden. Cup winners qualify for the Europa League, although most will have gained entry to Europe via the Premiership anyway, so their berth is passed down rather than the cup runners-up qualify.

The Scottish League Cup, introduced in 1946 14 years before its English counterpart, involves all SPFL clubs from the previous season. The current format is a group stage followed by knock-out rounds. Scottish clubs competing in Europe are usually exempt from the group stage, allowing the winners of Highland and Lowland Leagues to compete in eight groups of five.

Each team plays four games, facing their group opponents either home or away. If a game is drawn, a penalty shoot-out decides who gets a bonus point to add to the one already won.

The eight group winners plus three best runners-up join the European competitors in the Second Round. The knock-out rounds are decided by one game, after extra-time and penalties if needed. The semi-finals and December’s final take place at a neutral venue, usually Hampden. The winners do not qualify for Europe.

Of Scotland’s many other knock-out competitions, mention must be made of the Scottish Challenge Cup, featuring all 42 SPFL clubs, the Premiership represented by under-21 teams, plus eight from the Highland and Lowland Leagues, and four from the top tiers in Northern Ireland and Wales.

Of the city-based tournaments, the Glasgow Cup was once prestigious but now features the youth teams of Celtic and Rangers, and senior sides put out by Clyde, Queen’s Park and Partick Thistle. Regional trophies also date back to the earliest days of the game, the North Caledonian Cup and Aberdeenshire cups to 1887, Fifeshire to 1882, Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire to 1879.

FOOTBALL WEEKENDS

The season from kick-off to crunch time

The Scottish Premiership starts in late July and runs until the end of May. Saturday 3pm is sacrosanct but there will be a noon game on the Sunday, and/or the Saturday. As in England, football during the Christmas festivities is big business, usually Boxing Day, with the winter break over two or three weeks in January.

The other three leagues begin the same weekend in late July, running until early May, allowing for play-offs in the middle of the month. Again, Saturday, 3pm is the hallowed time. With group games in the Scottish League Cup starting the second week of July, pre-season friendlies are scheduled for late June and early July.

ENTRY LEVEL

Buying tickets and wee bevvies

Celtic and Rangers apart, for most clubs you can pay on the day. Ticket offices are usually open during the week, with online purchases, too. Admission is around £15, £10 discounted, £5 for youths. Most Celtic and Rangers games sell out, although early rounds of the cup often provide an opportunity for casual visitors to experience Celtic Park or Ibrox.

Officially, alcohol is still banned in Scottish football stadiums, apart from hospitality areas, although there are increasing calls for these restrictions, dating back to 1980, to be rescinded. Several clubs introduced pilot schemes to sell real beer in stadium concourses from the start of 2025-26.

Football pubs abound – particularly in Glasgow but you’ll be surprised at what you might find in hidden corners of Stranraer, Kelty and Dumfries.